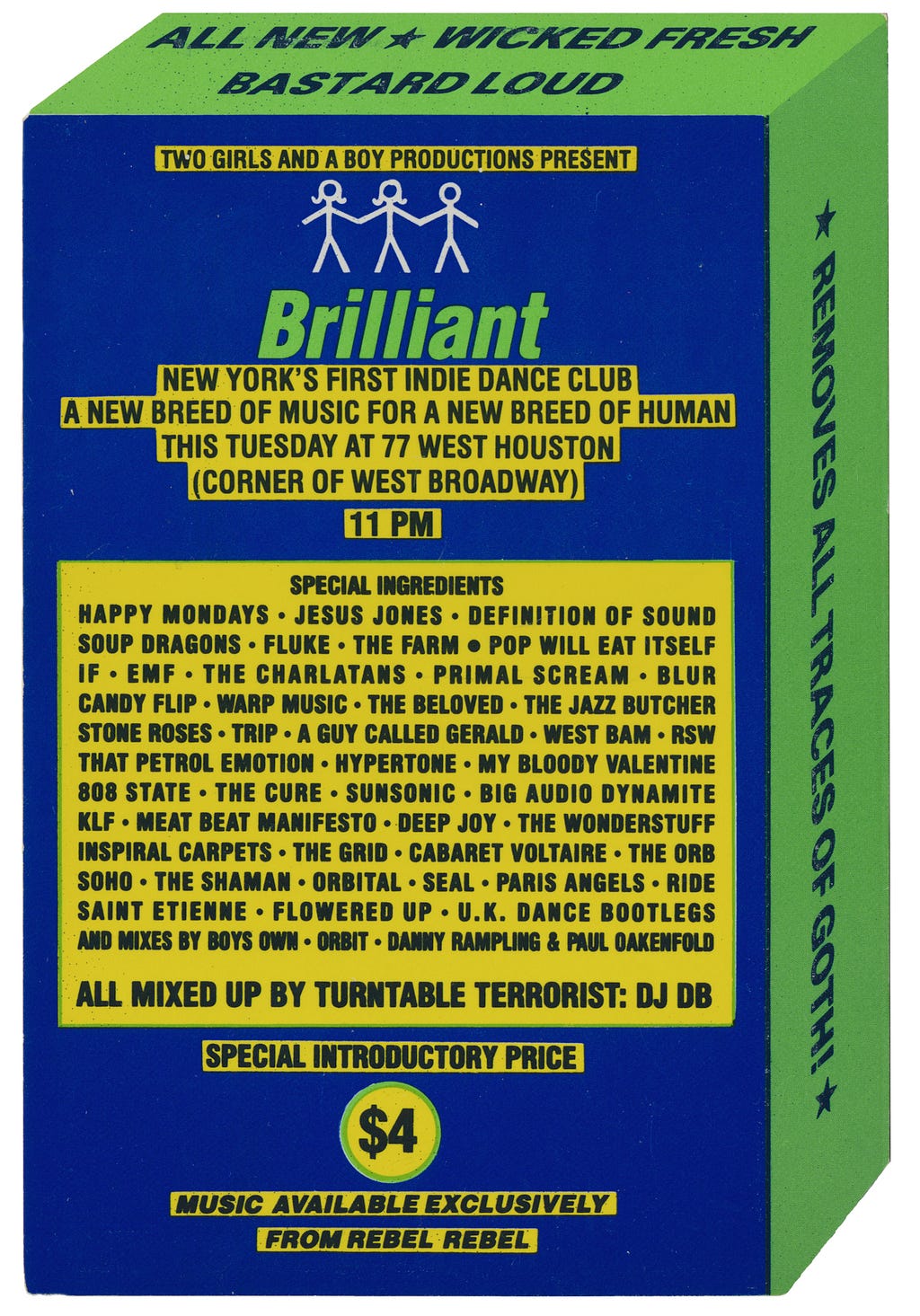

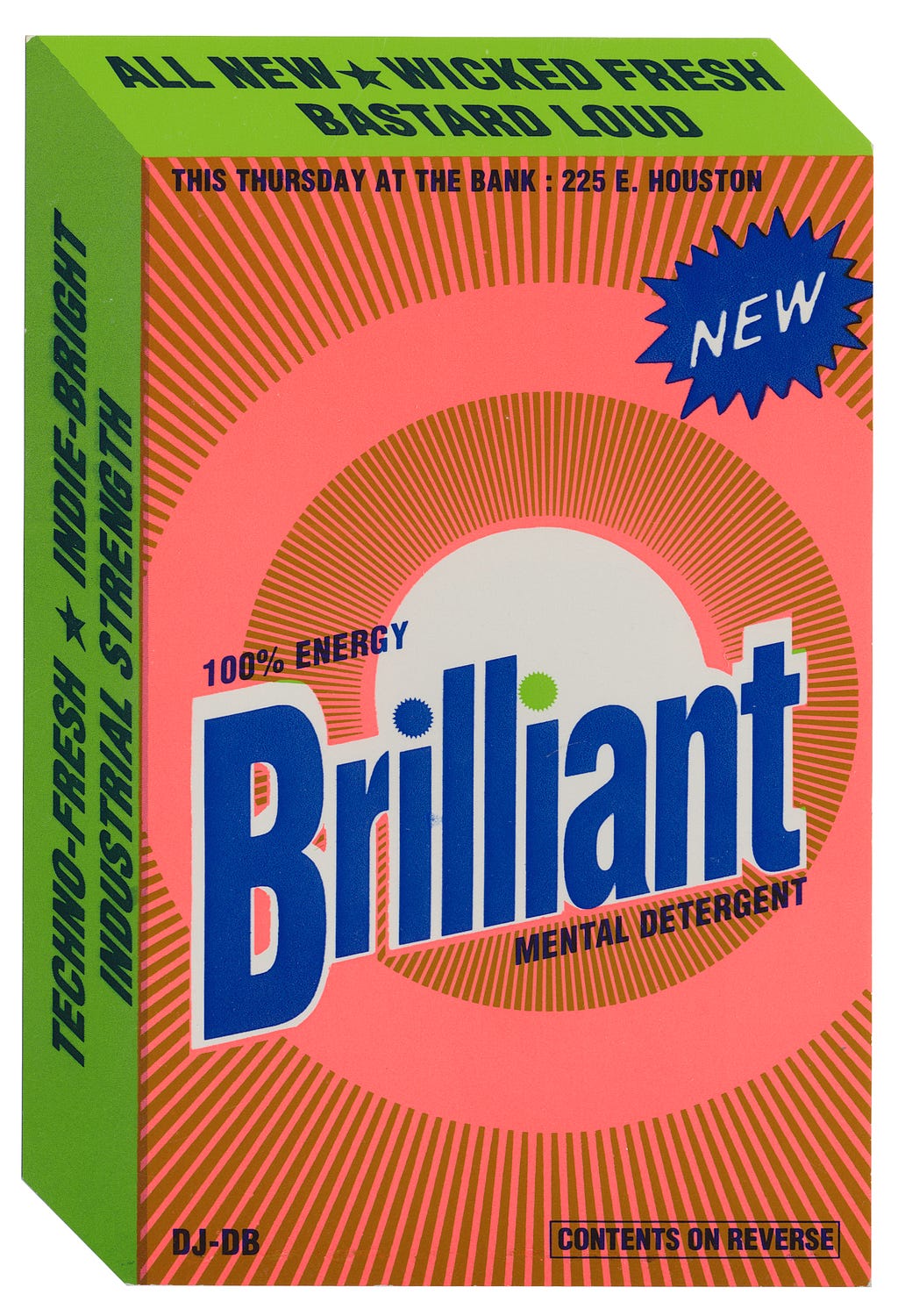

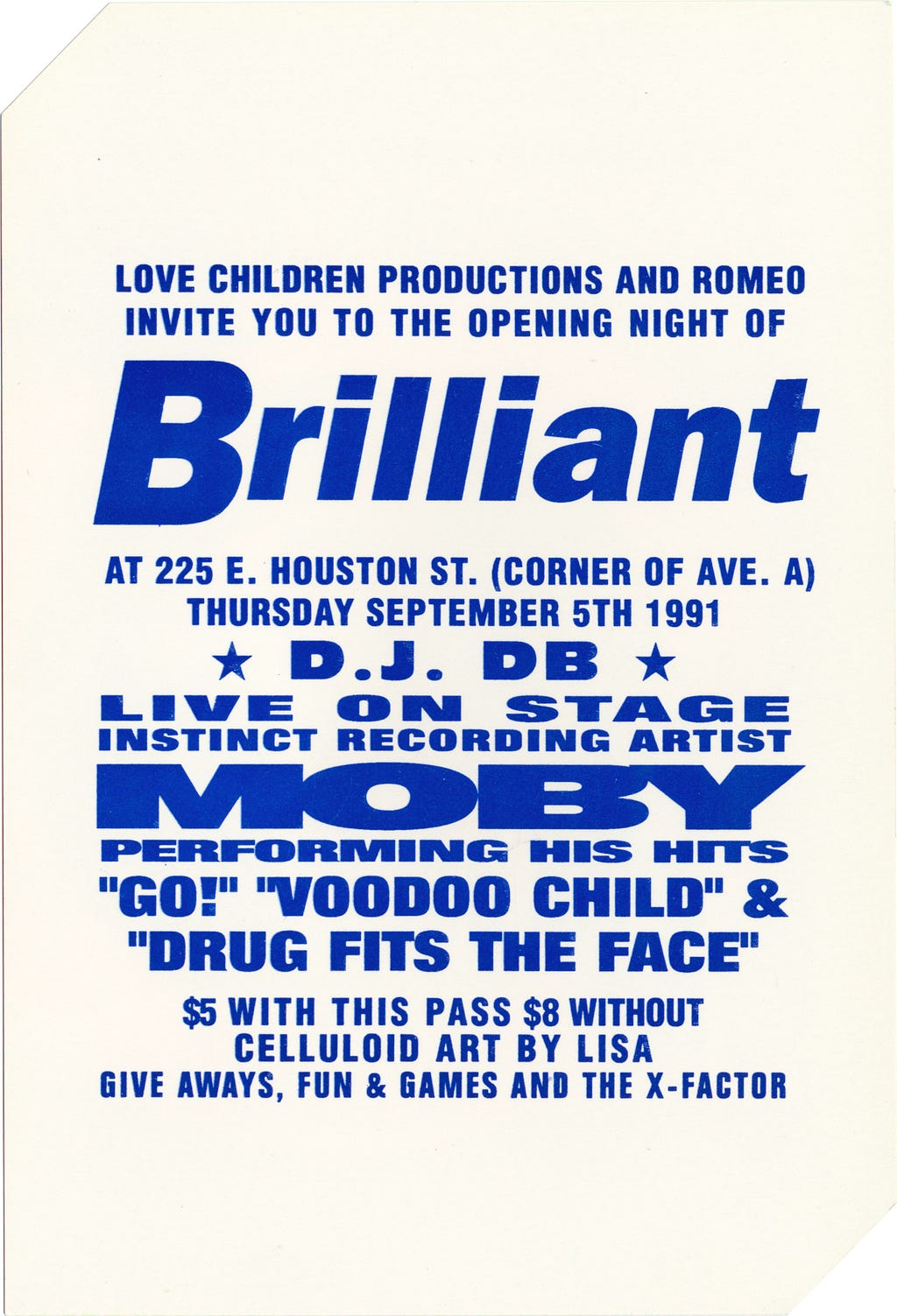

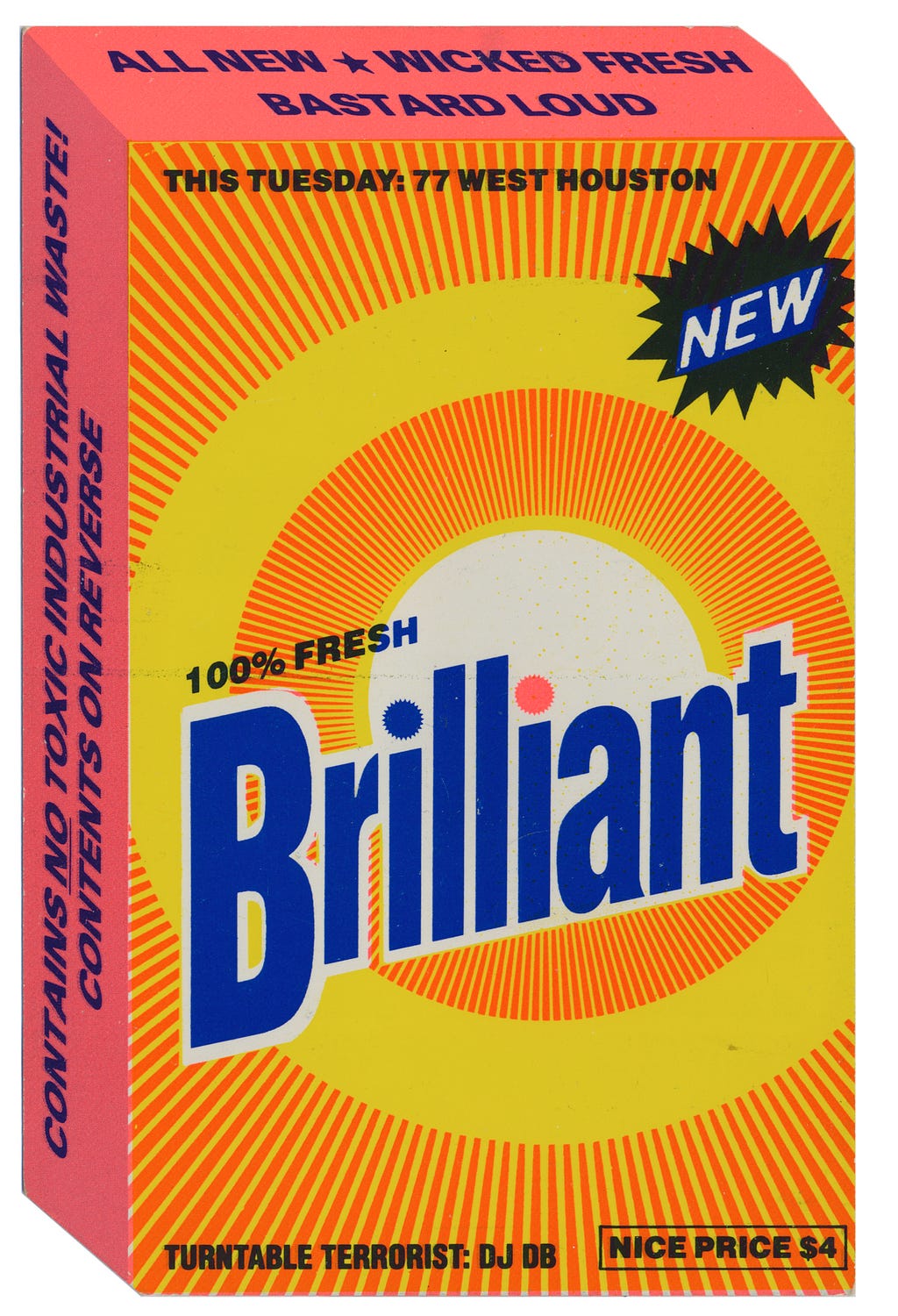

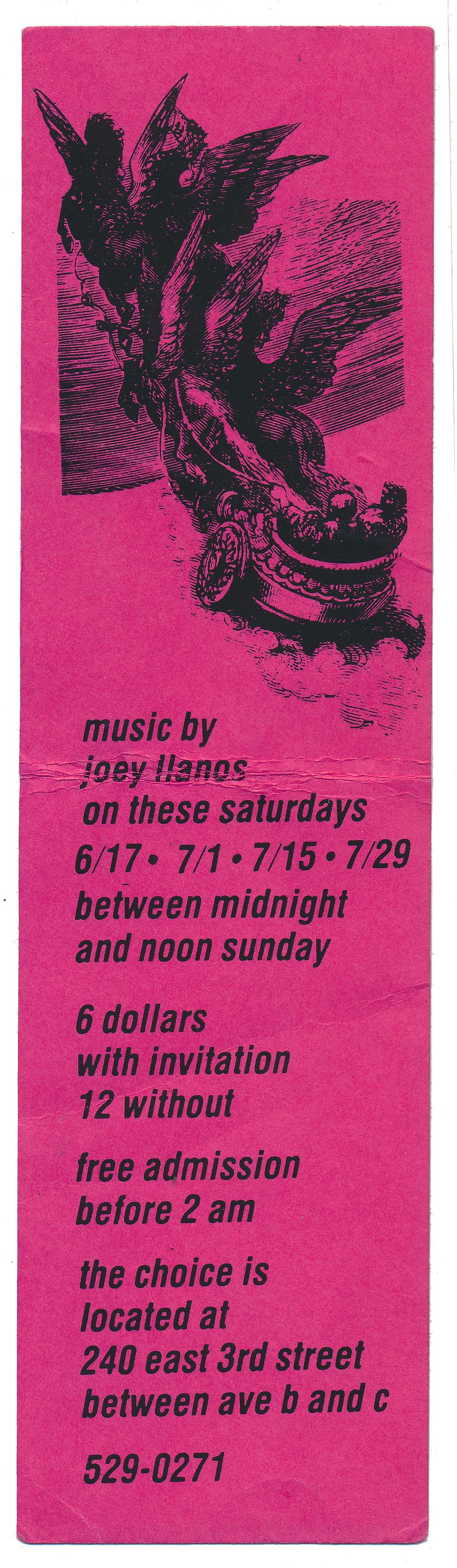

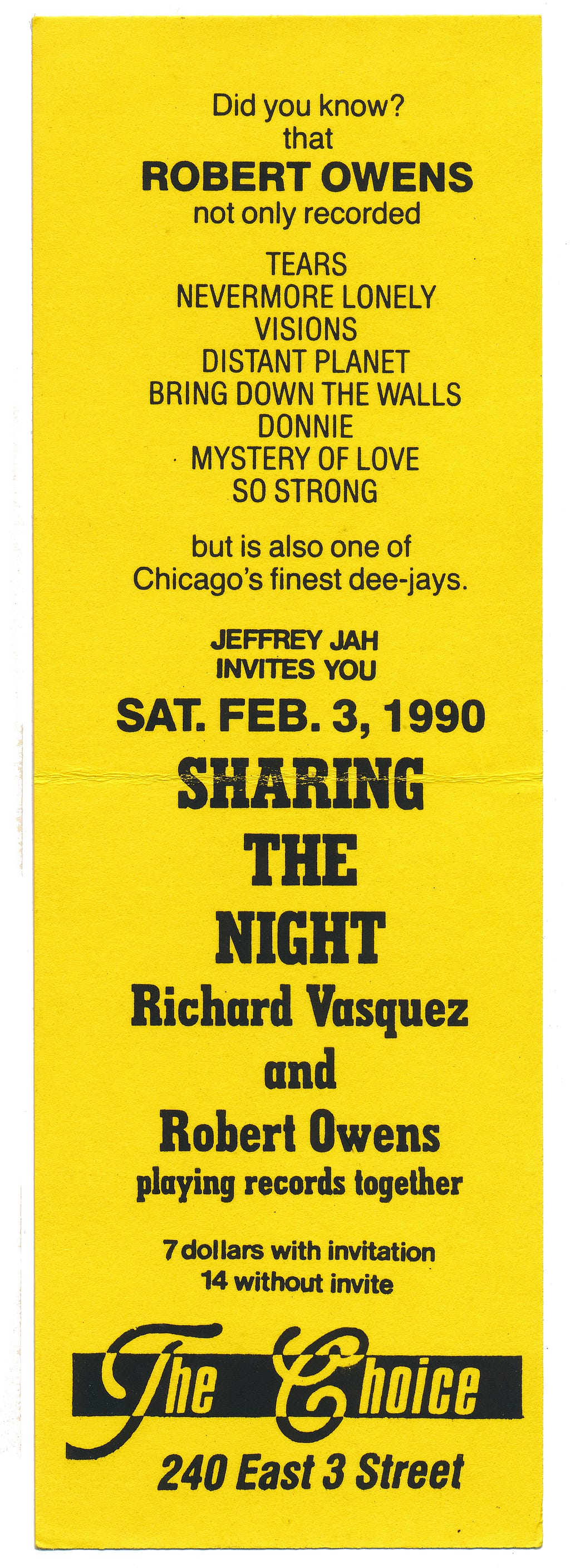

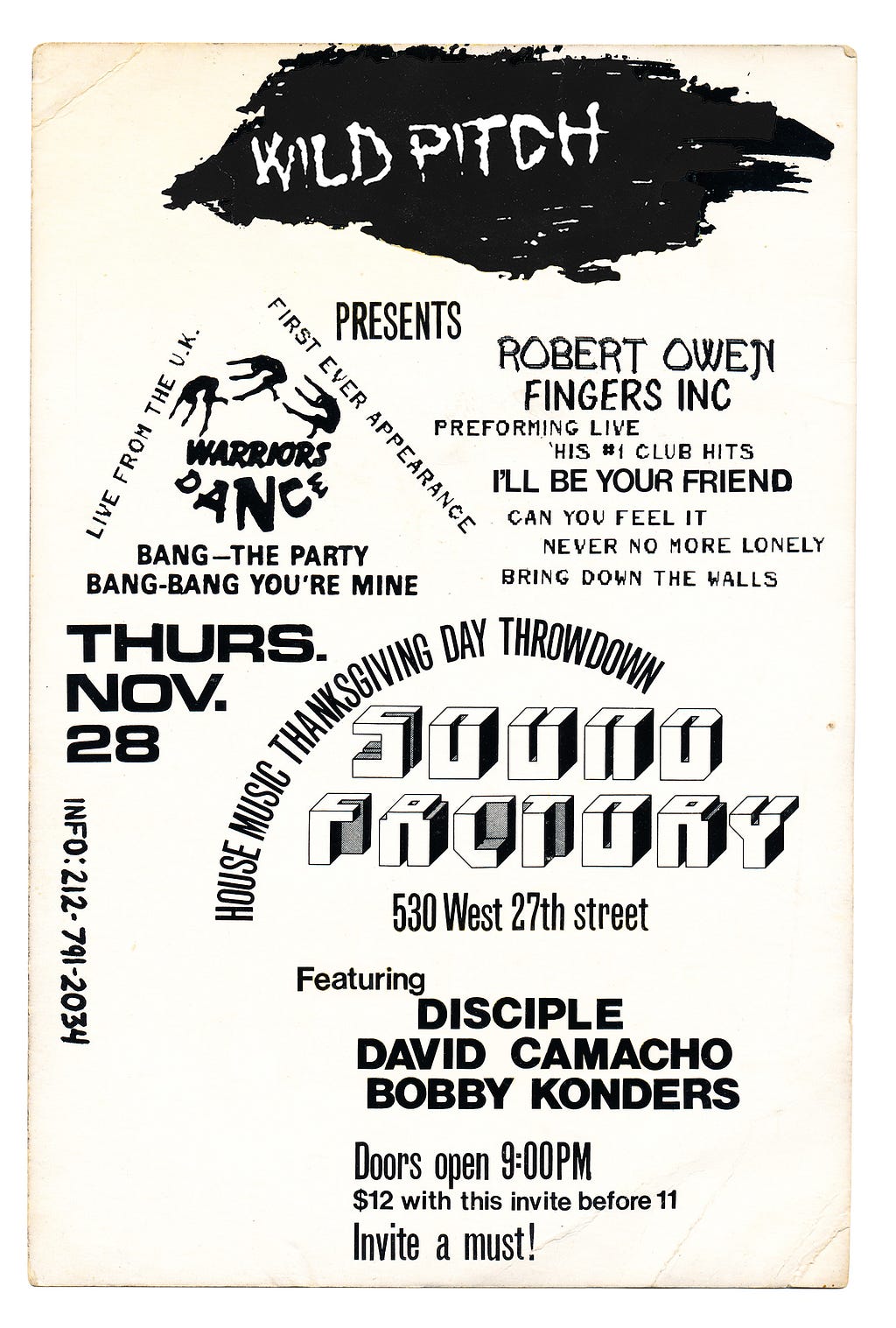

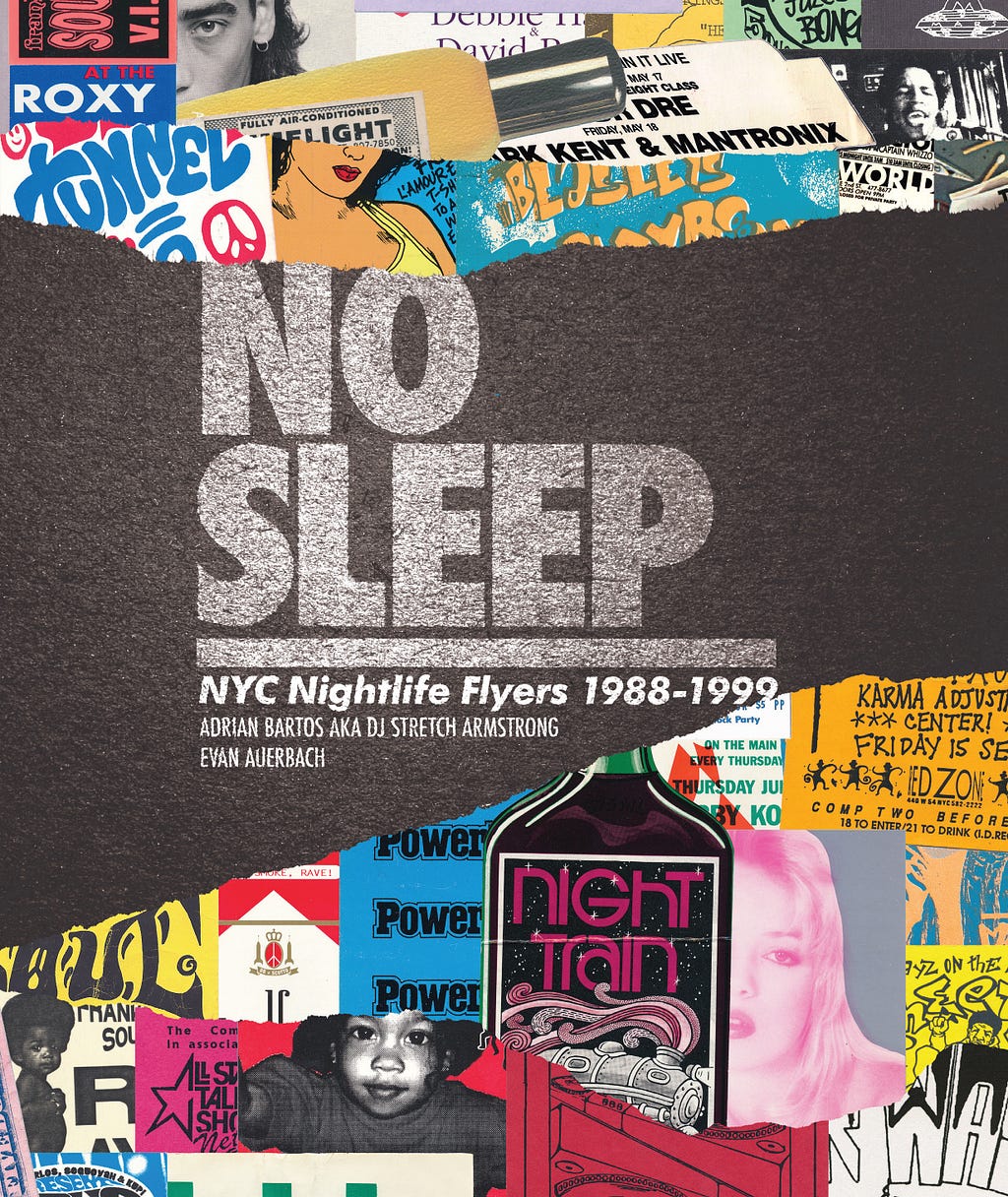

No Sleep is a visual history of the halcyon days of New York City club life as told through flyer art—gathered in a new volume by myself and Evan Auerbach. Spanning the late 1980s through the late 1990s, when nightlife buzz travelled via flyers and word of mouth, No Sleep features a collection of artwork from the personal archives of DJs, promoters, club kids, nightlife impresarios, and the artists themselves.

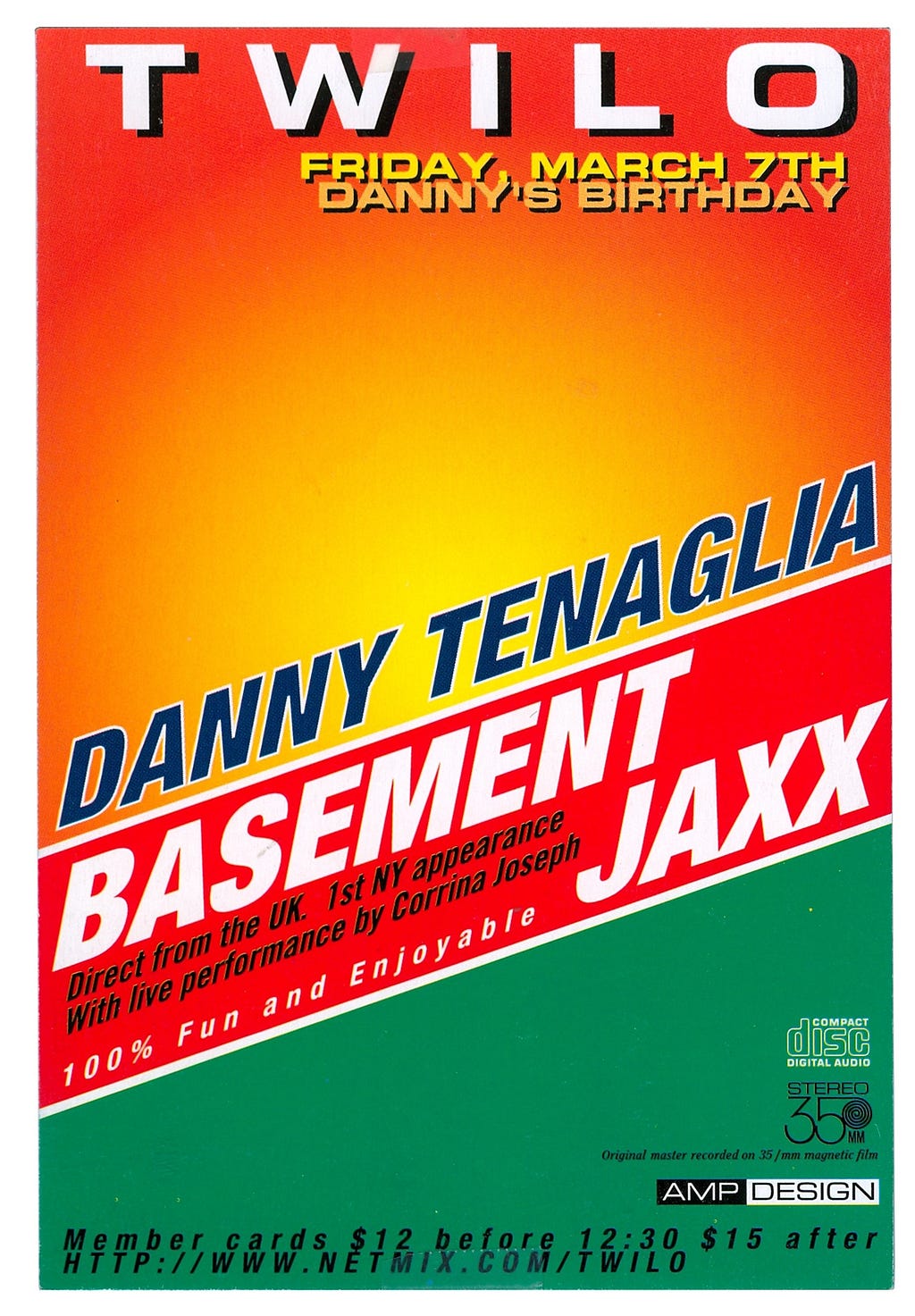

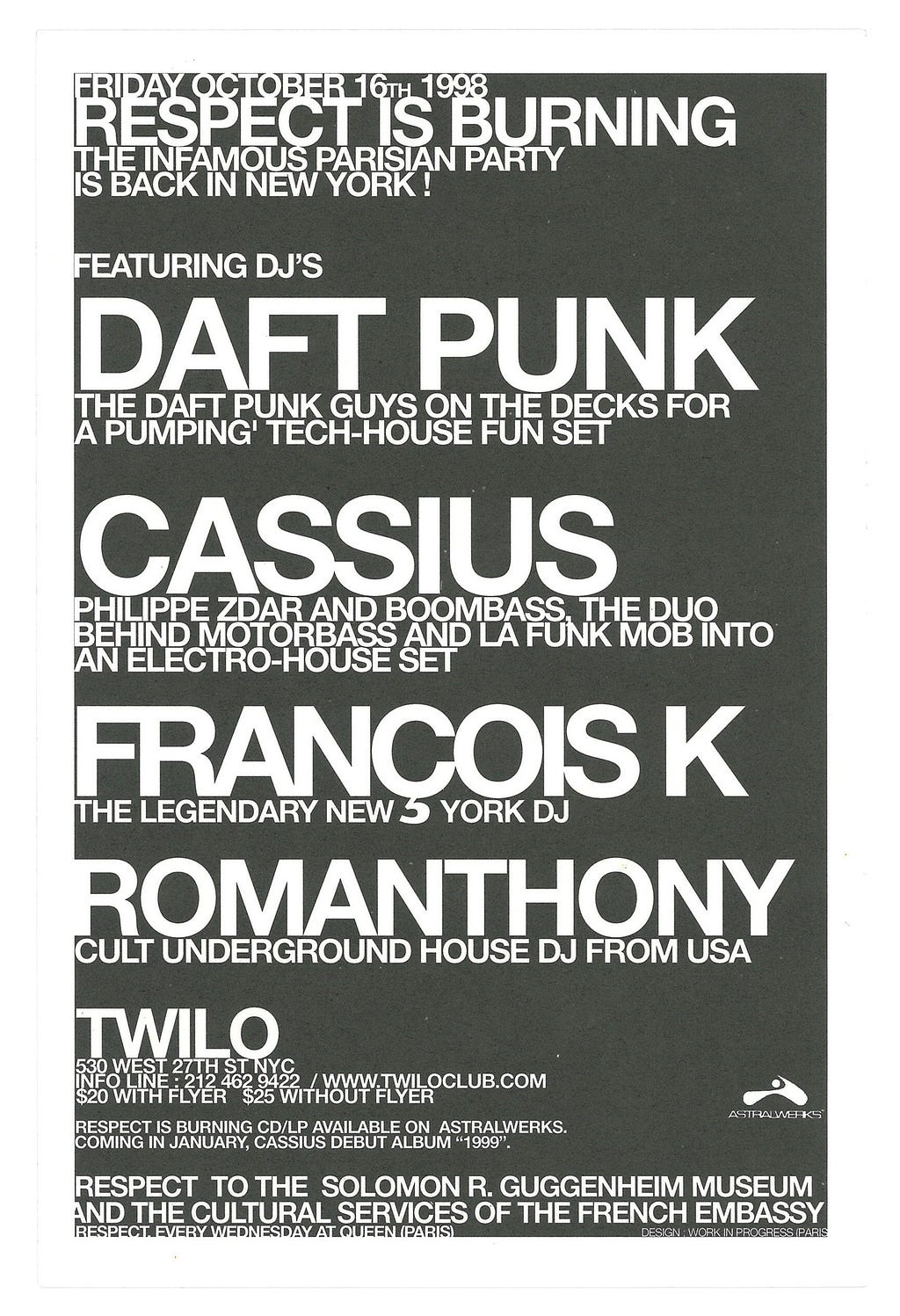

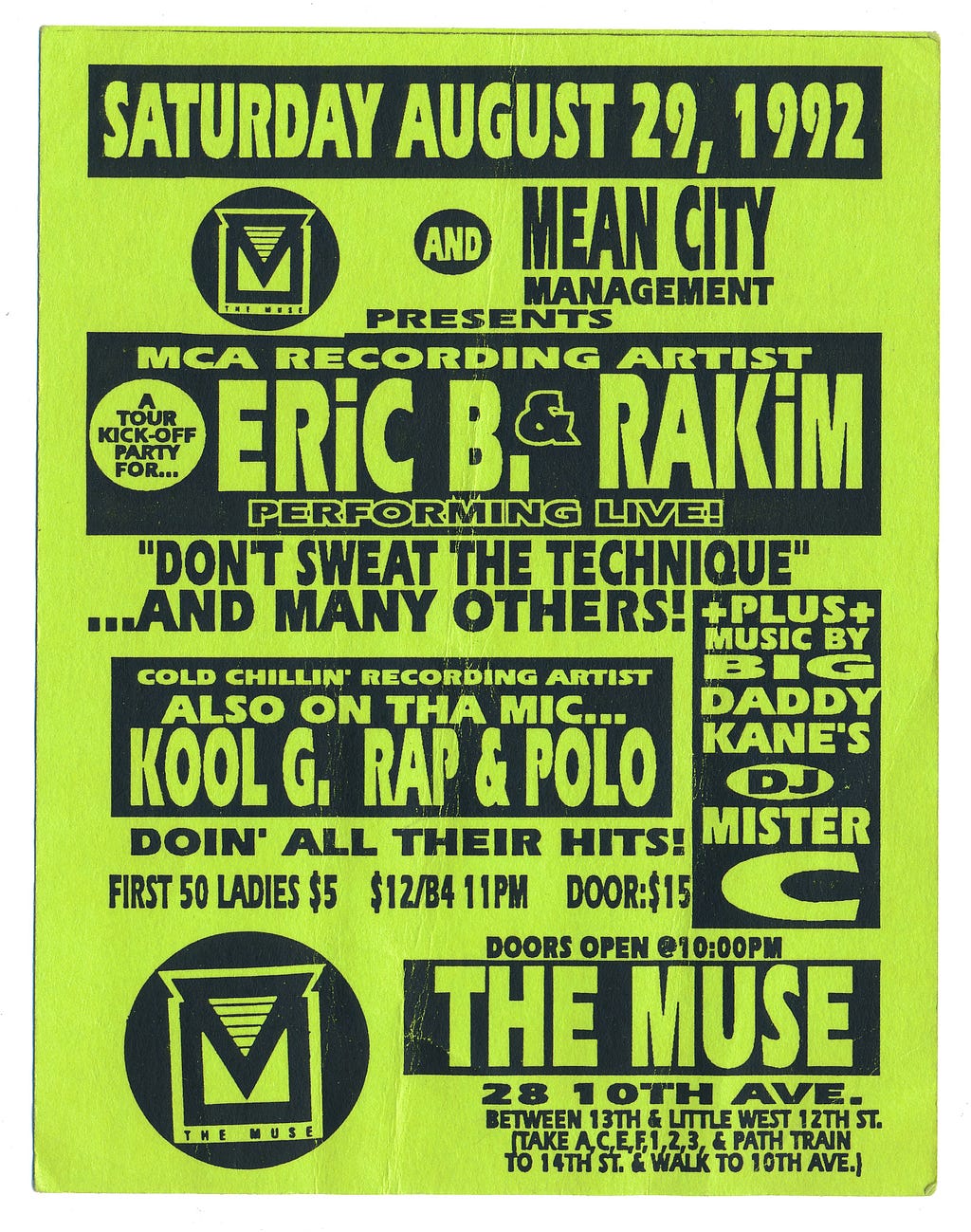

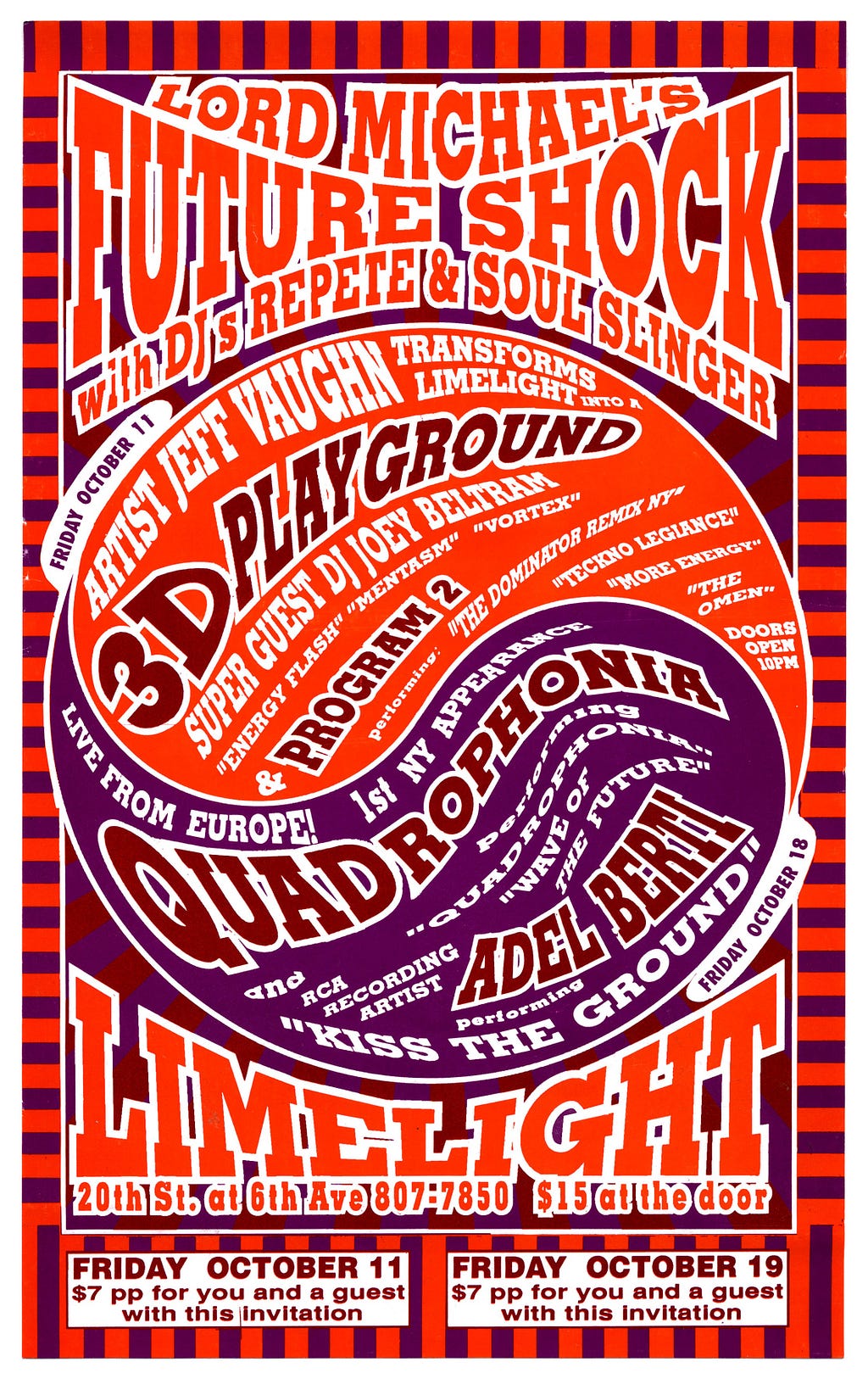

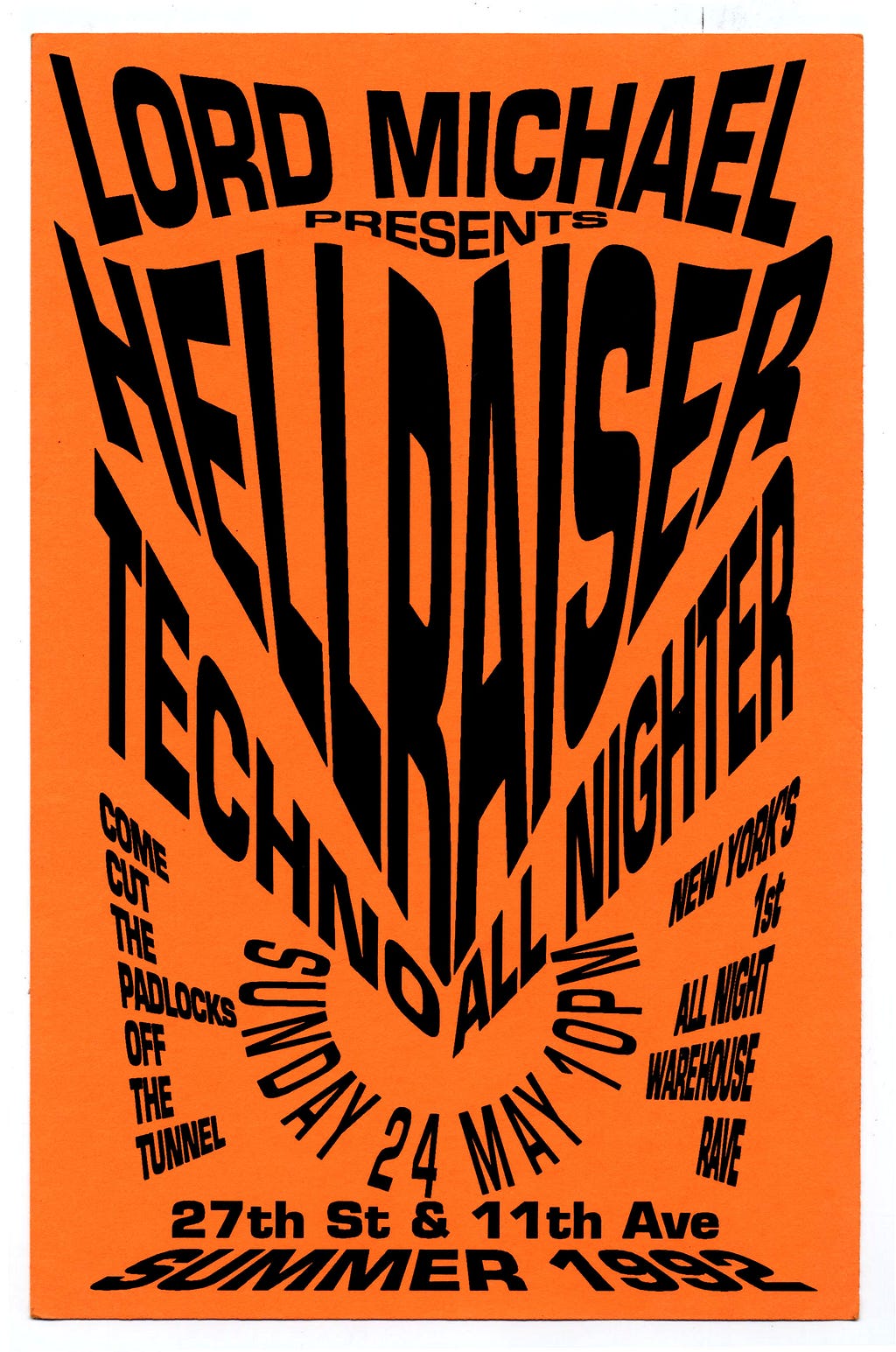

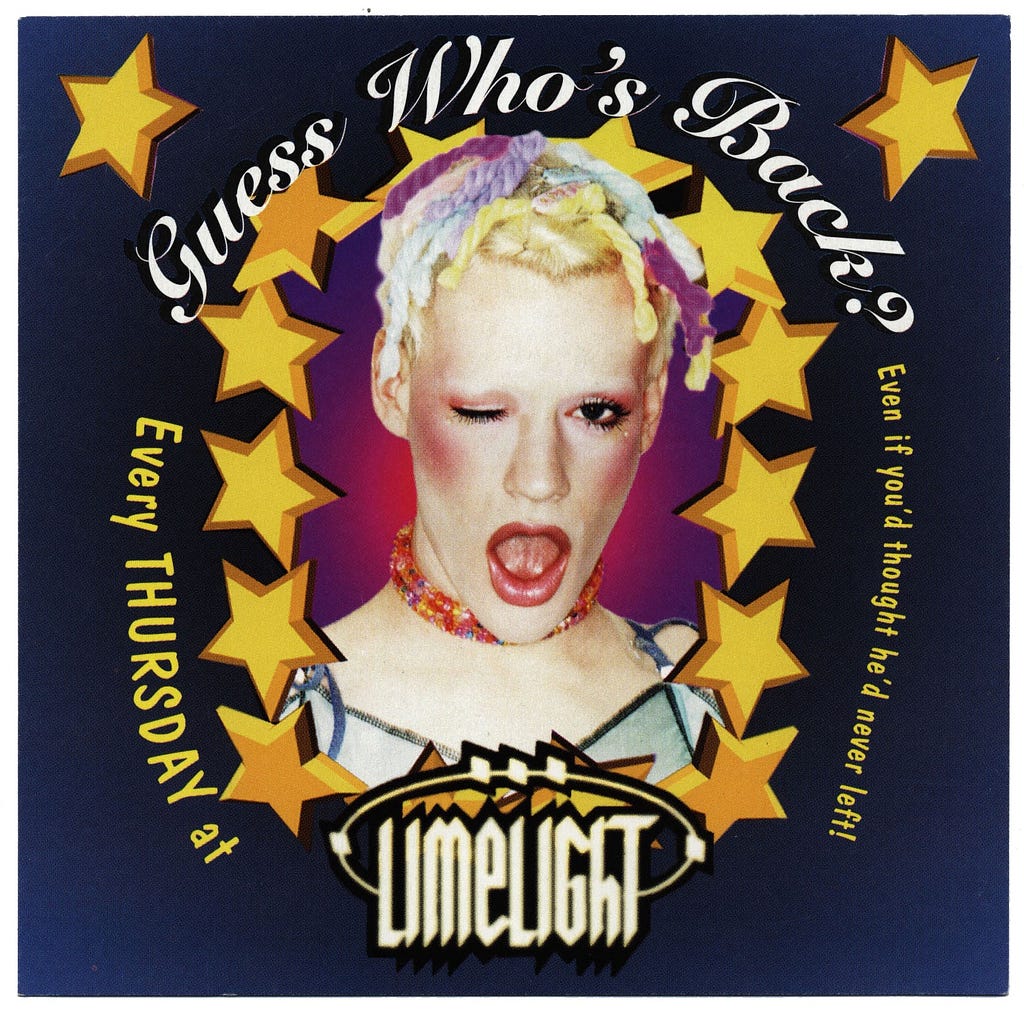

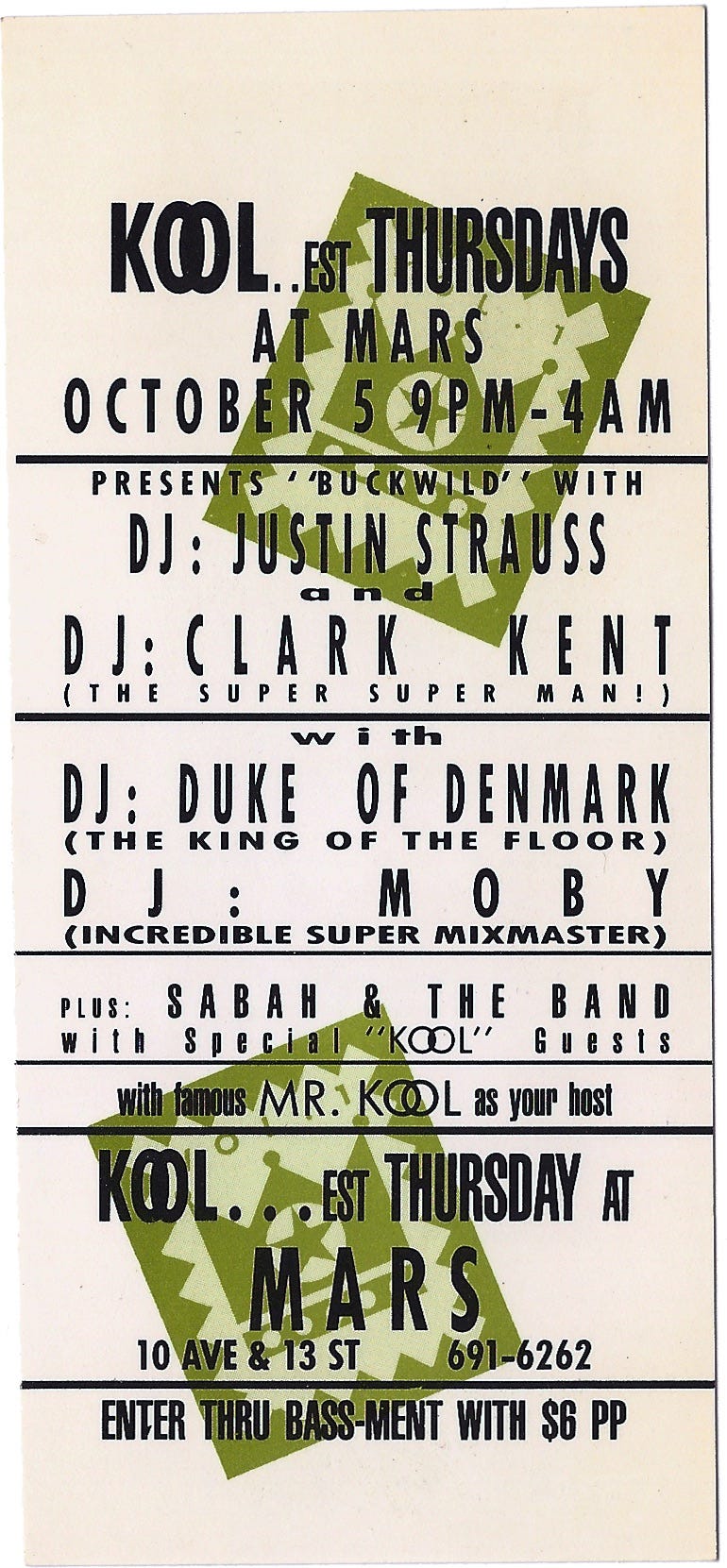

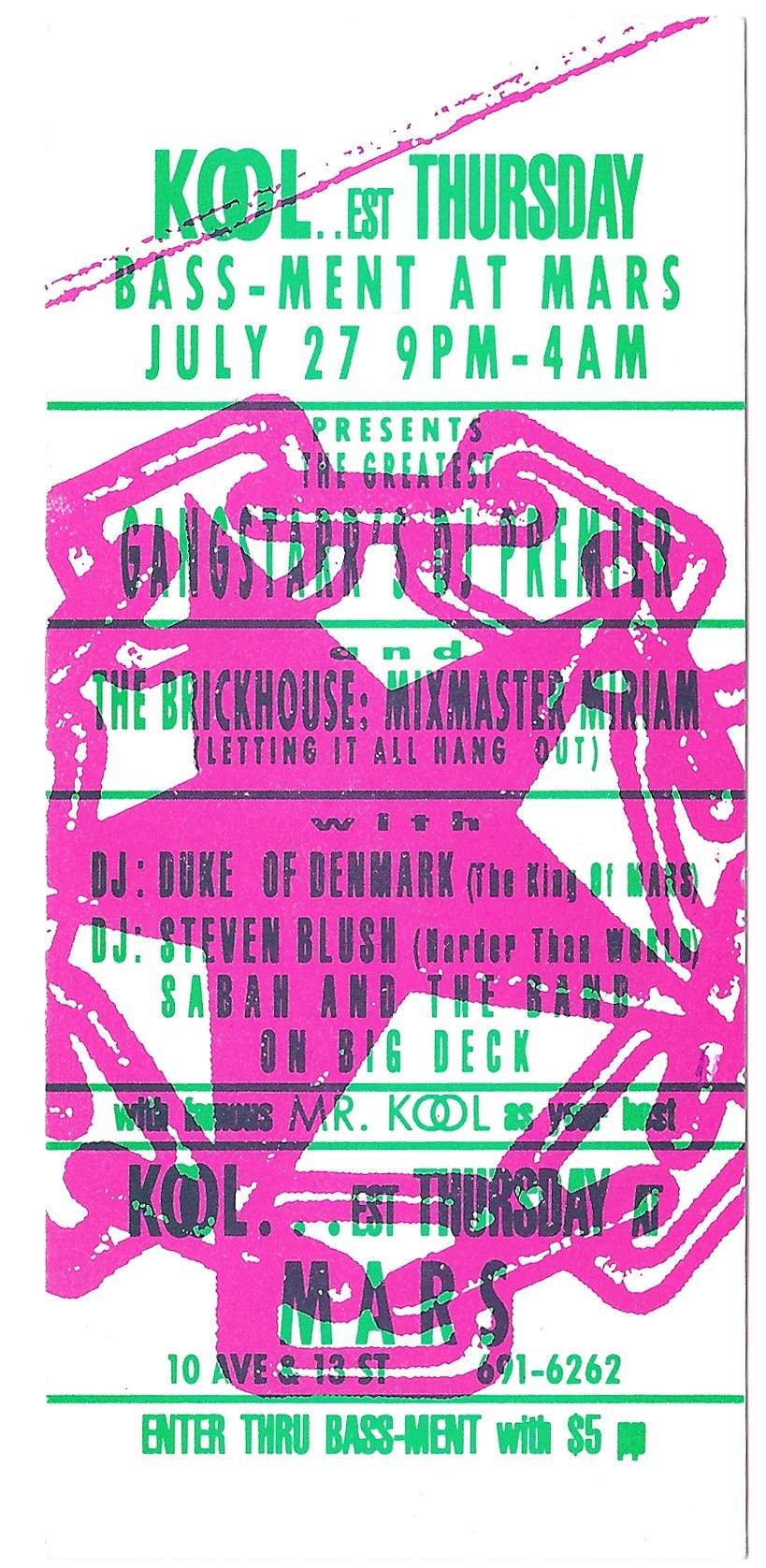

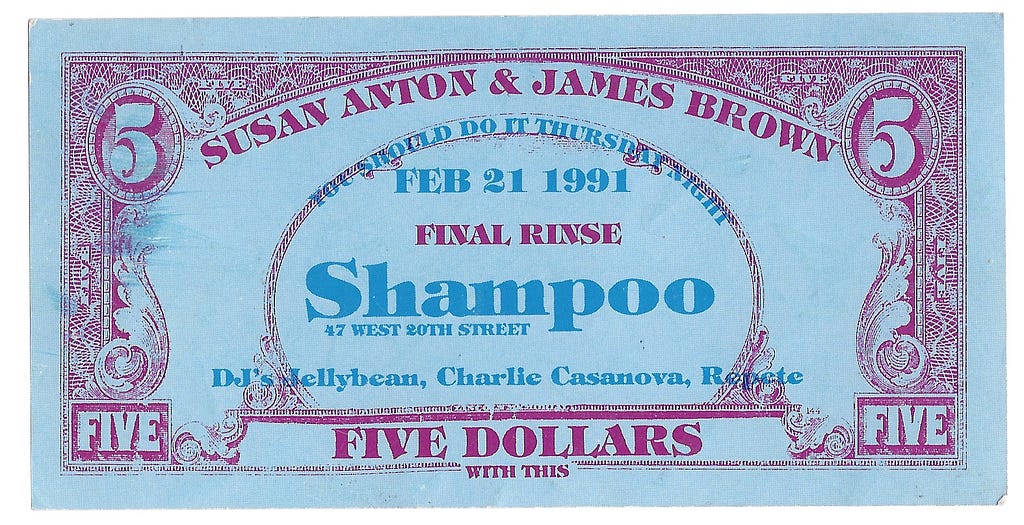

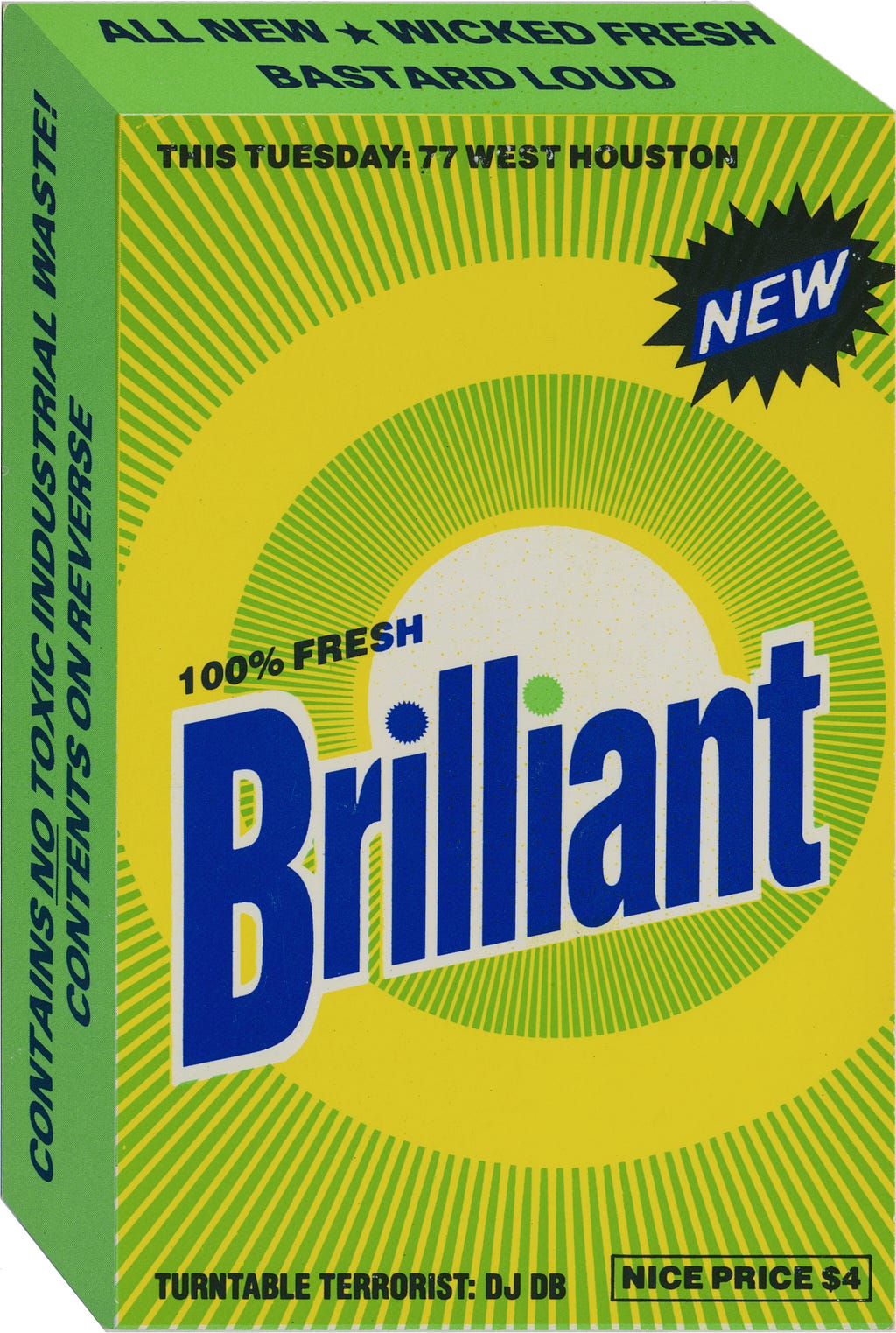

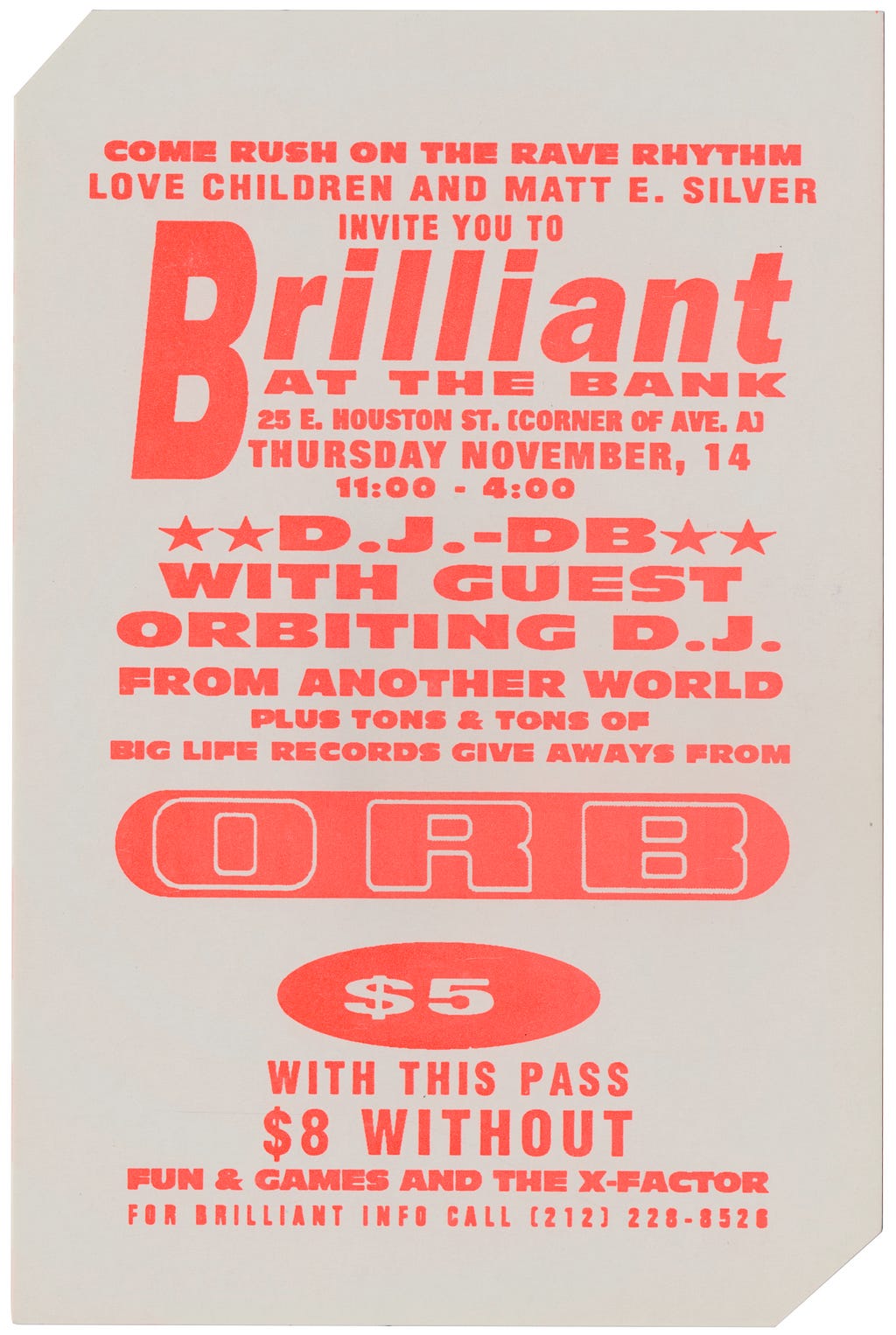

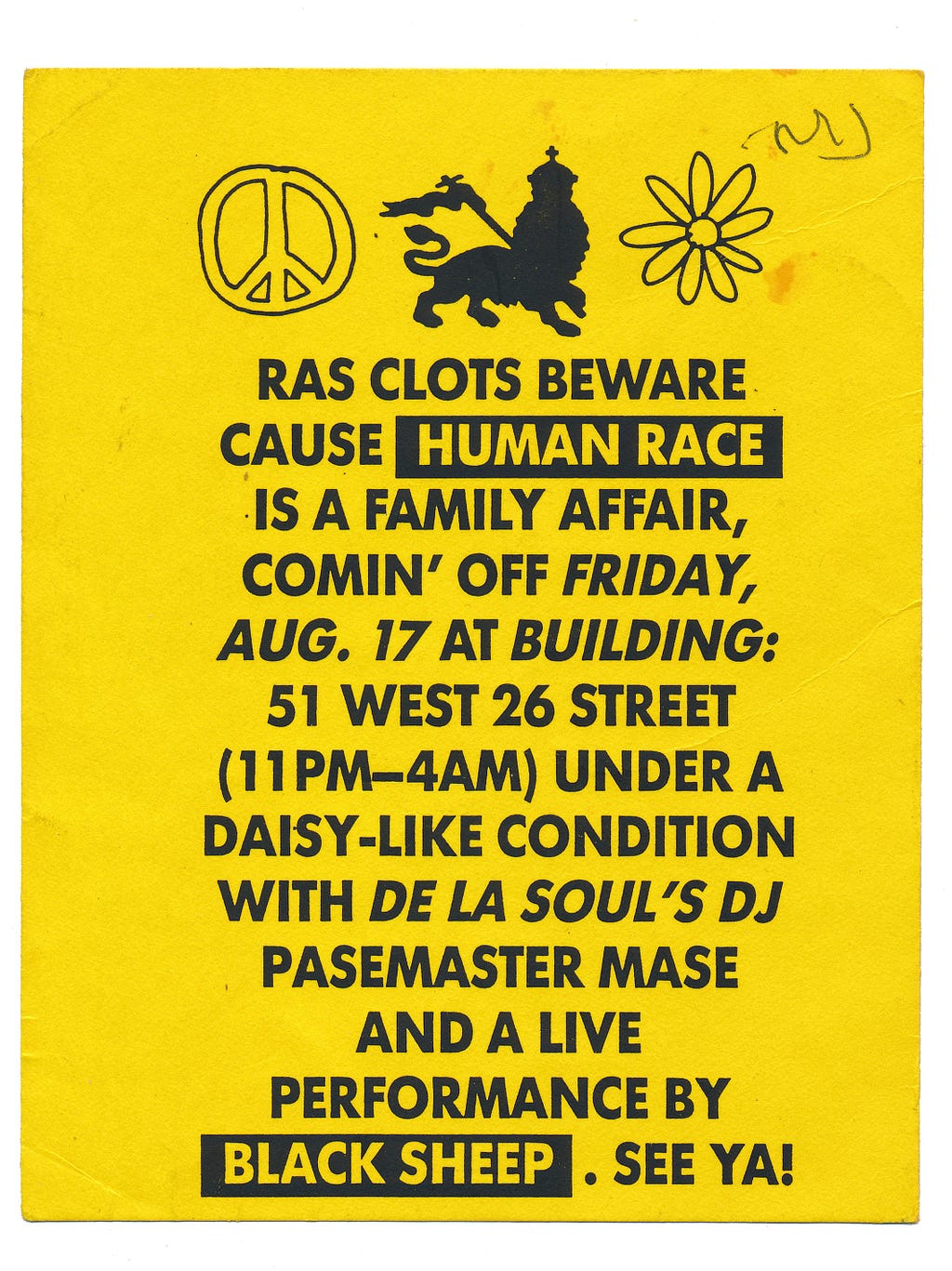

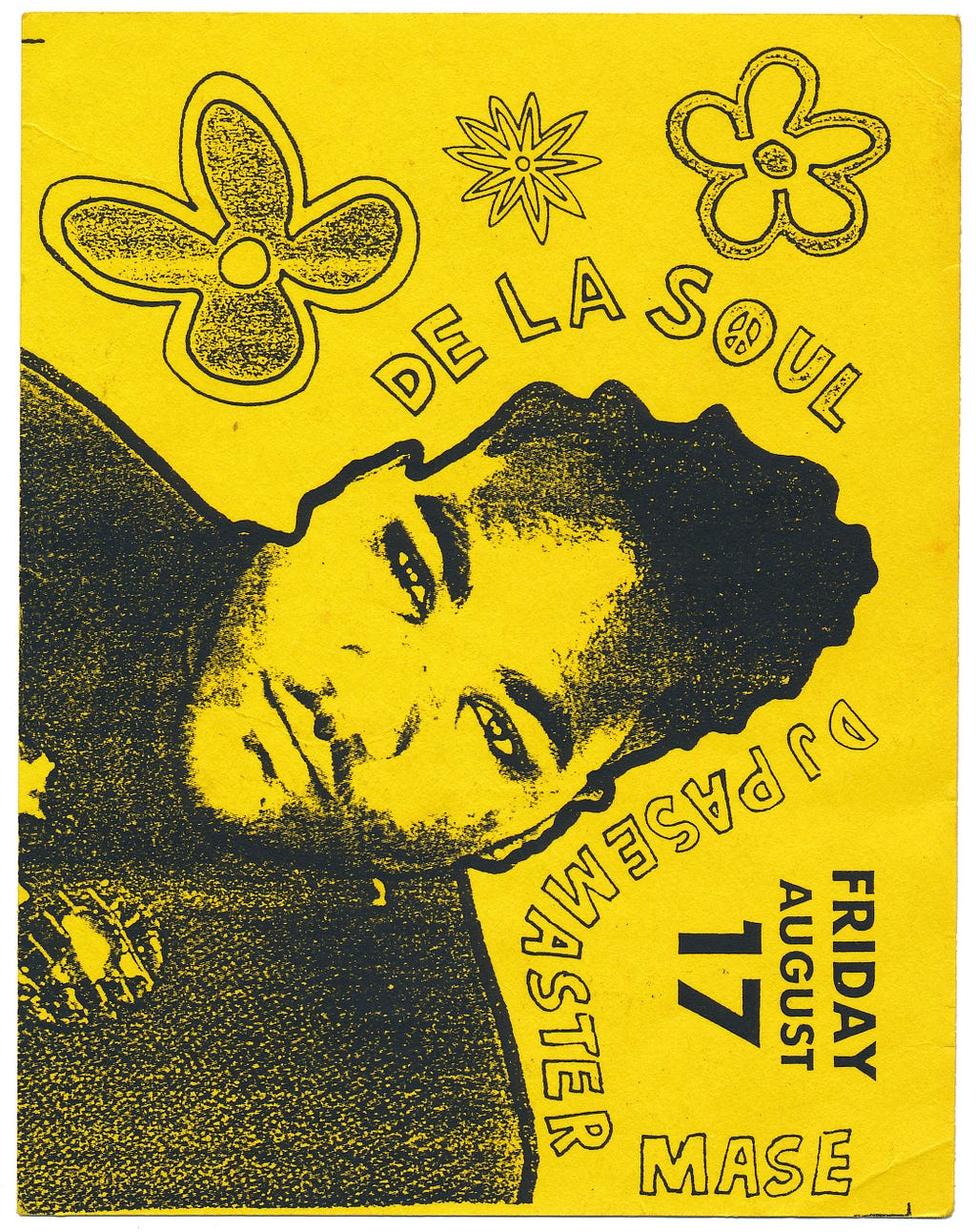

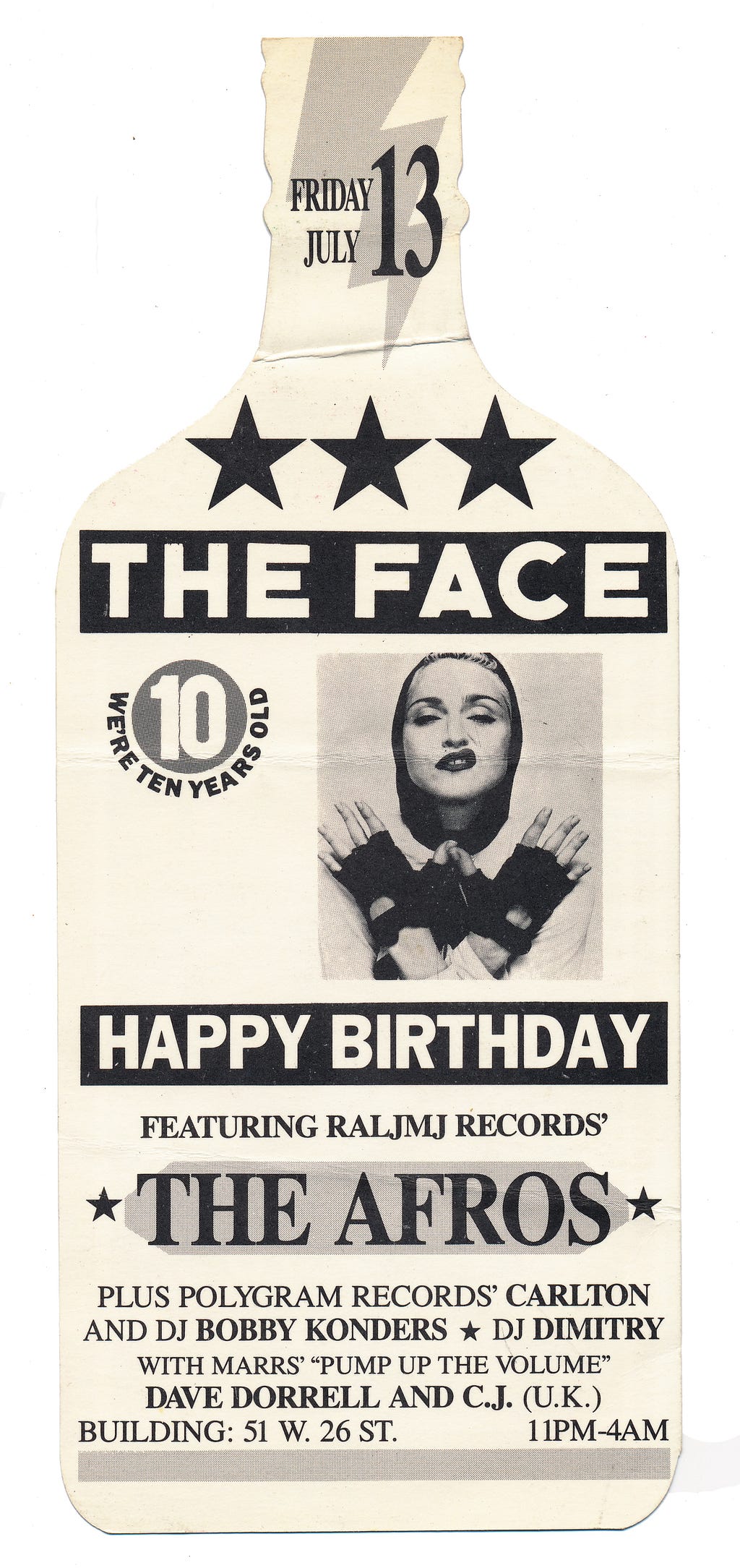

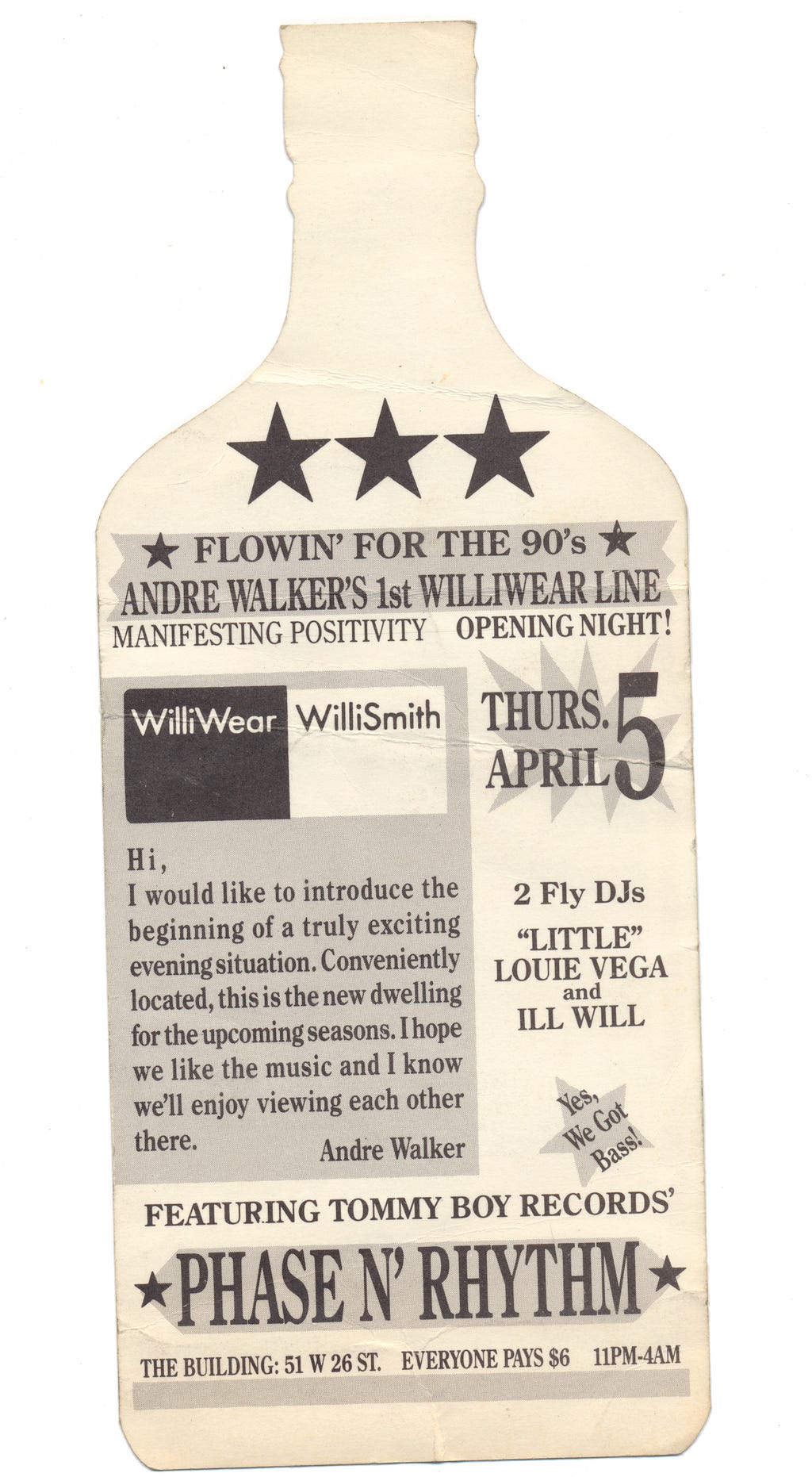

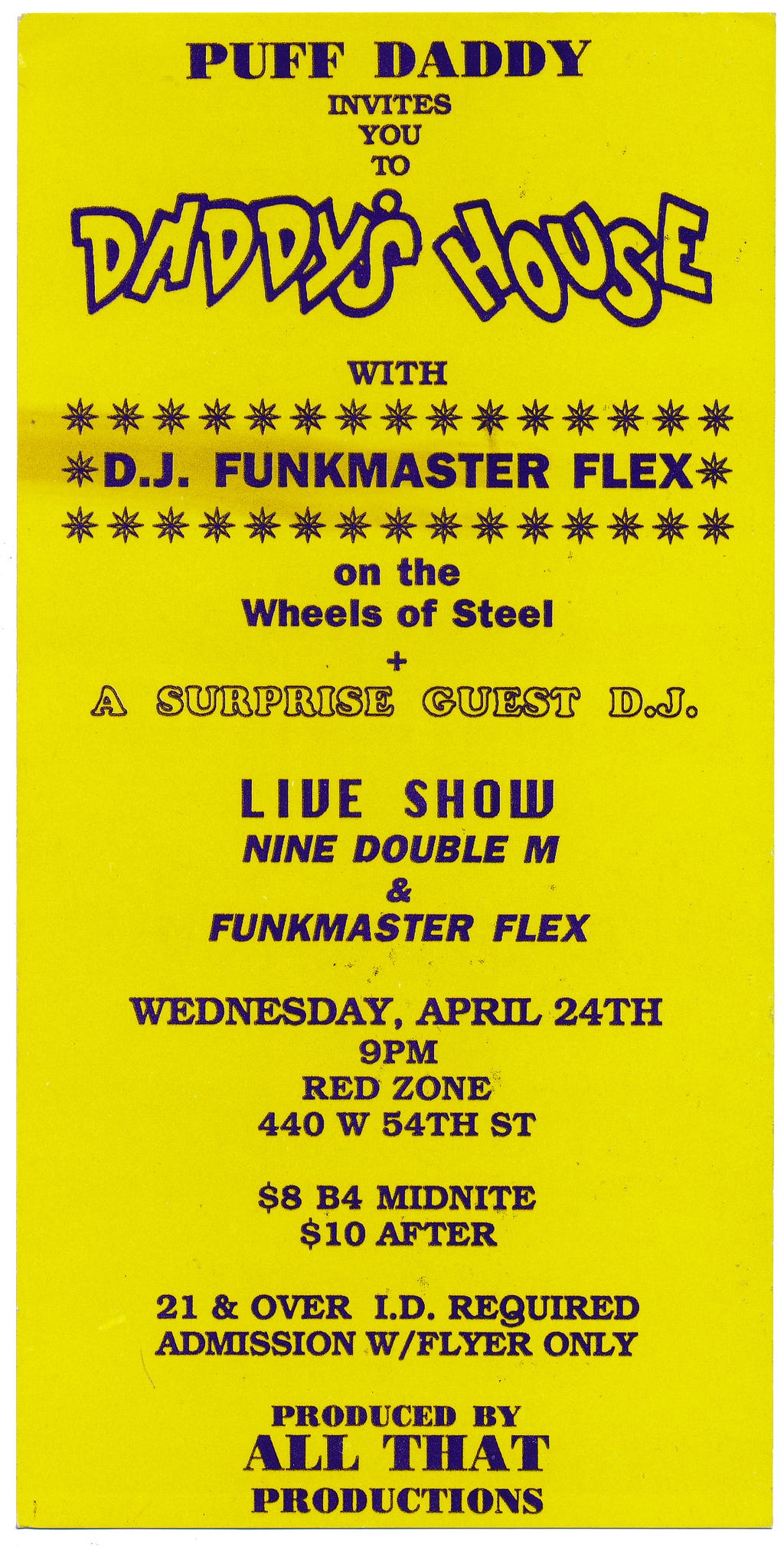

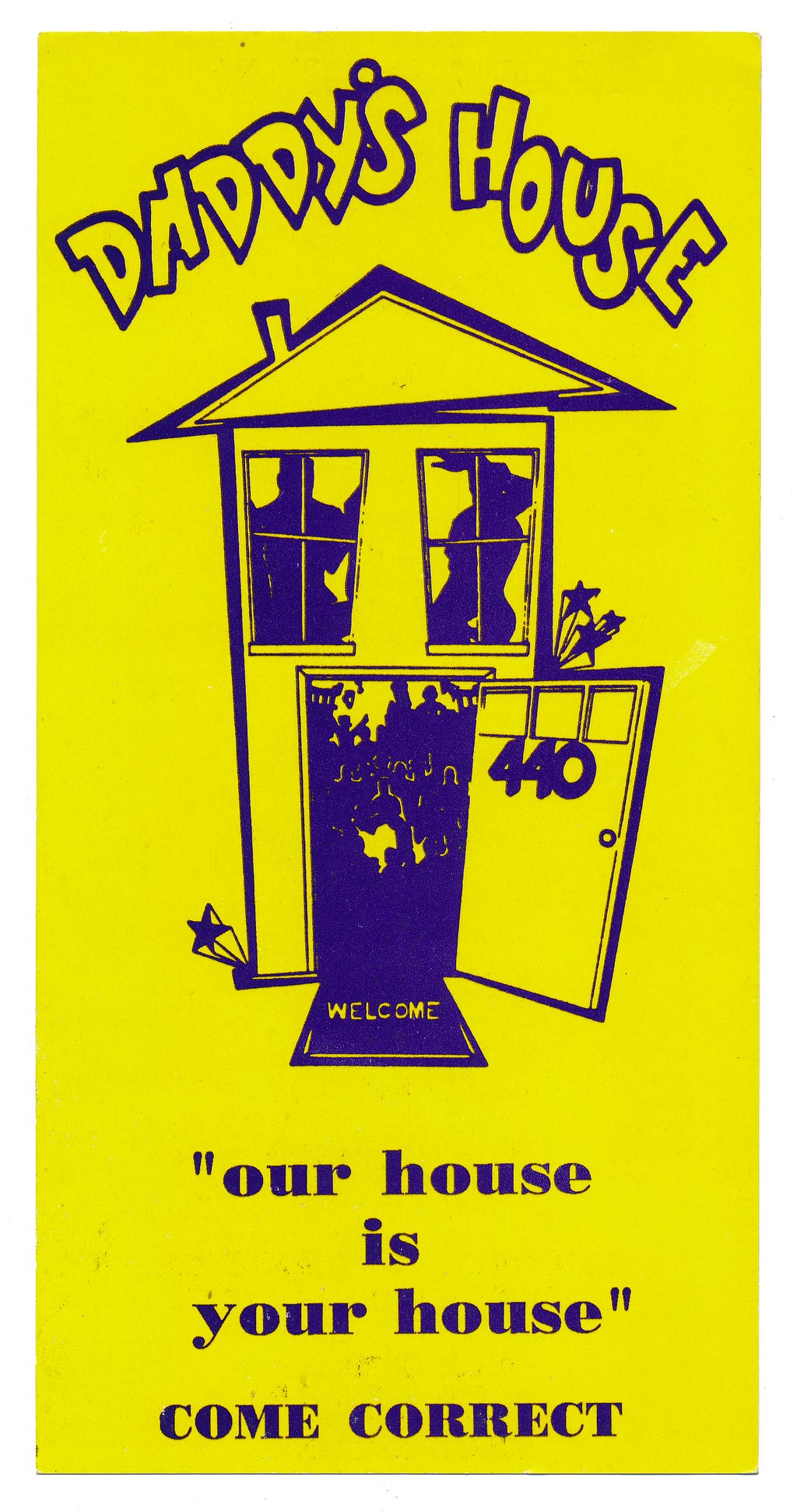

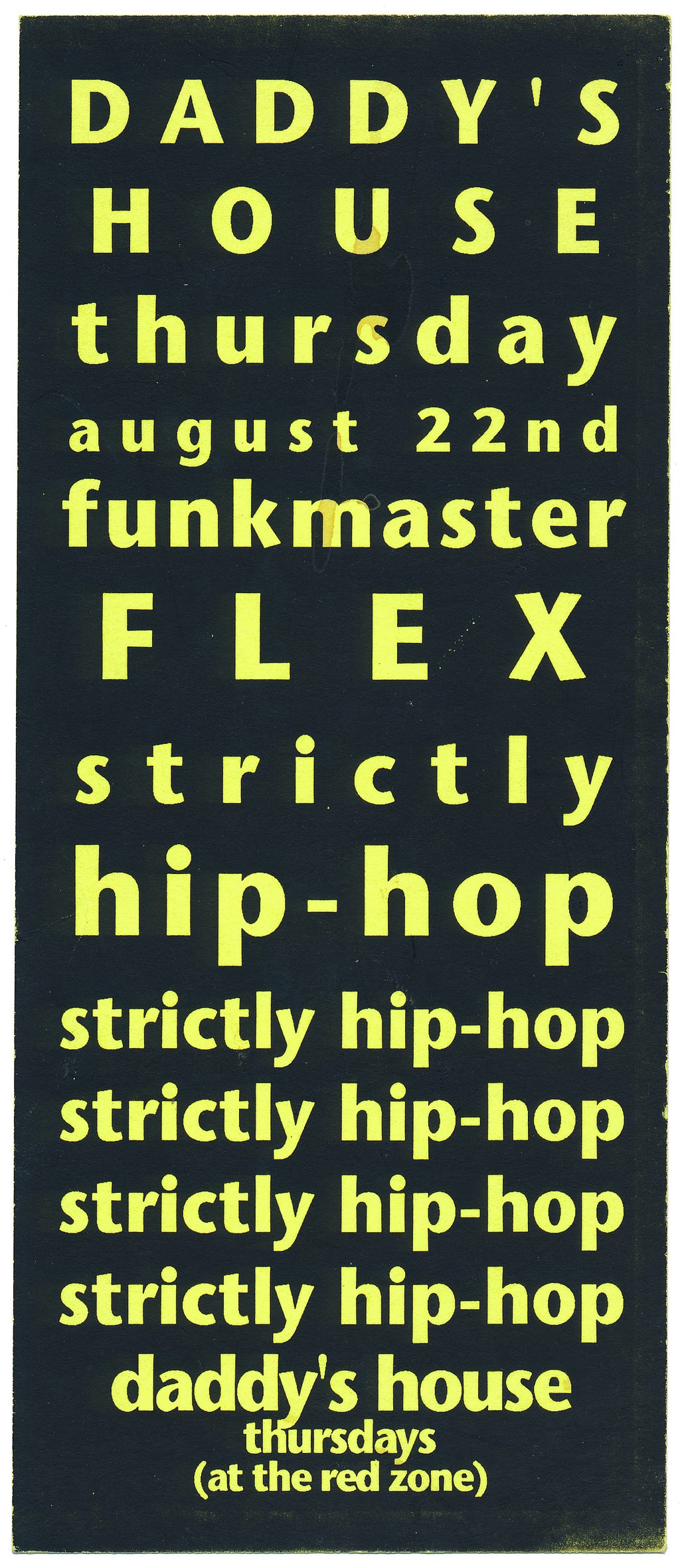

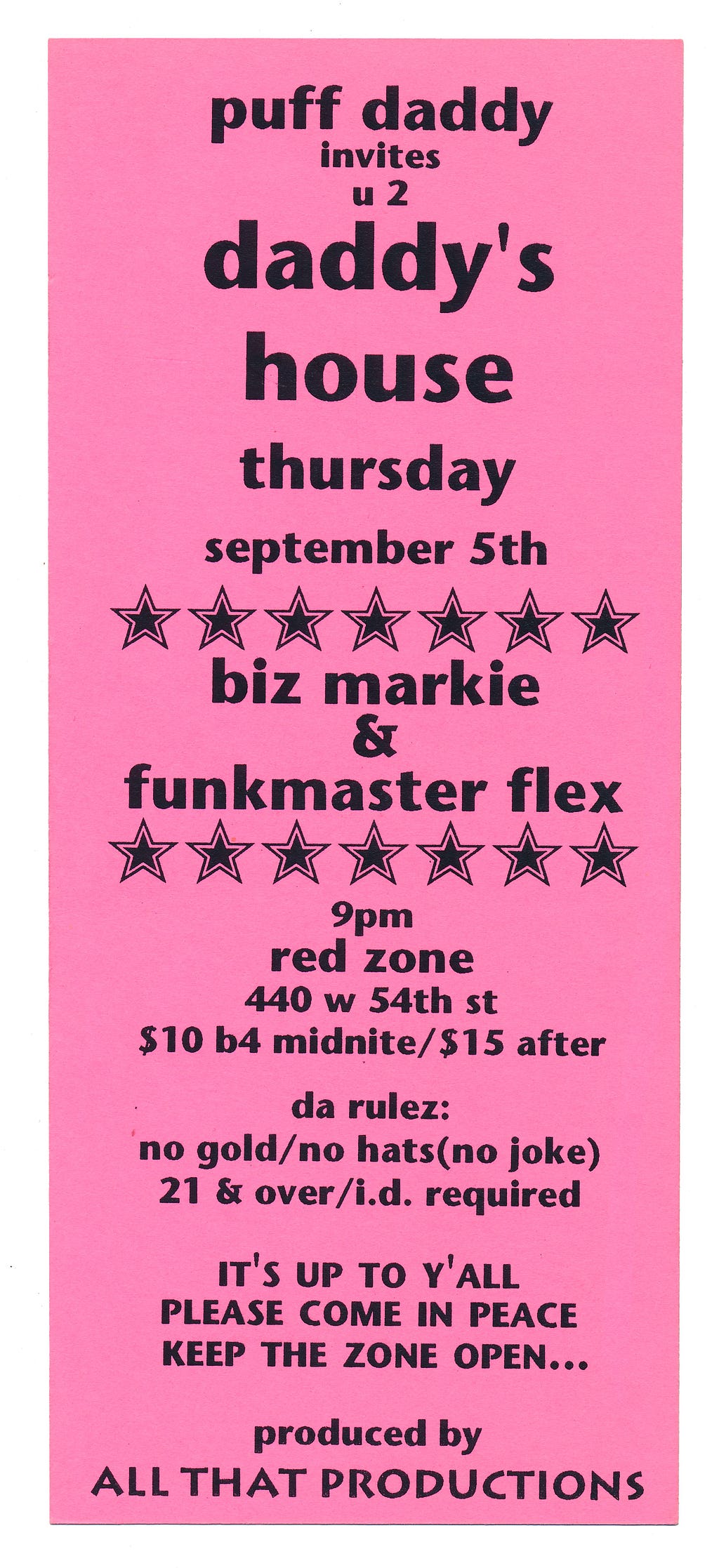

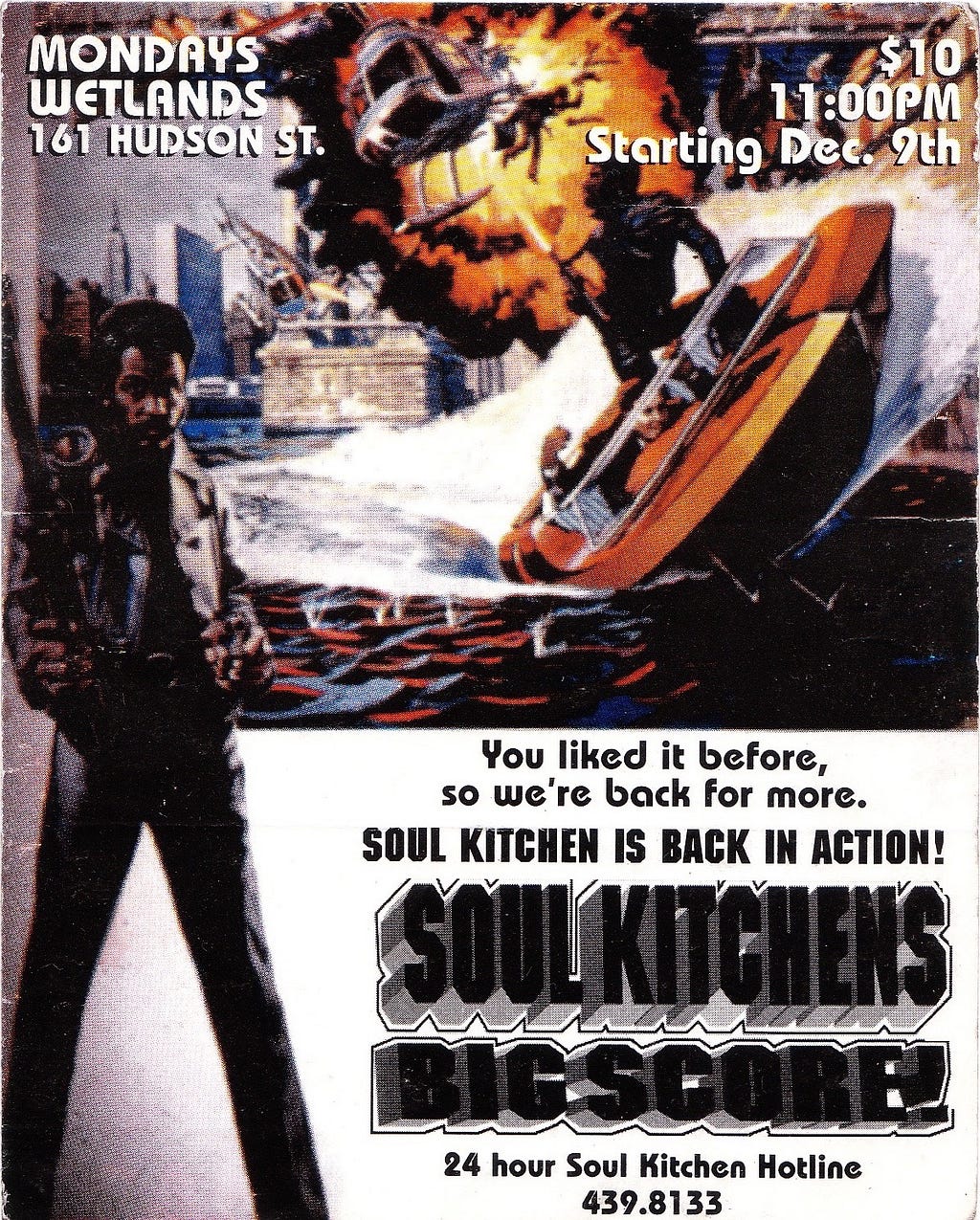

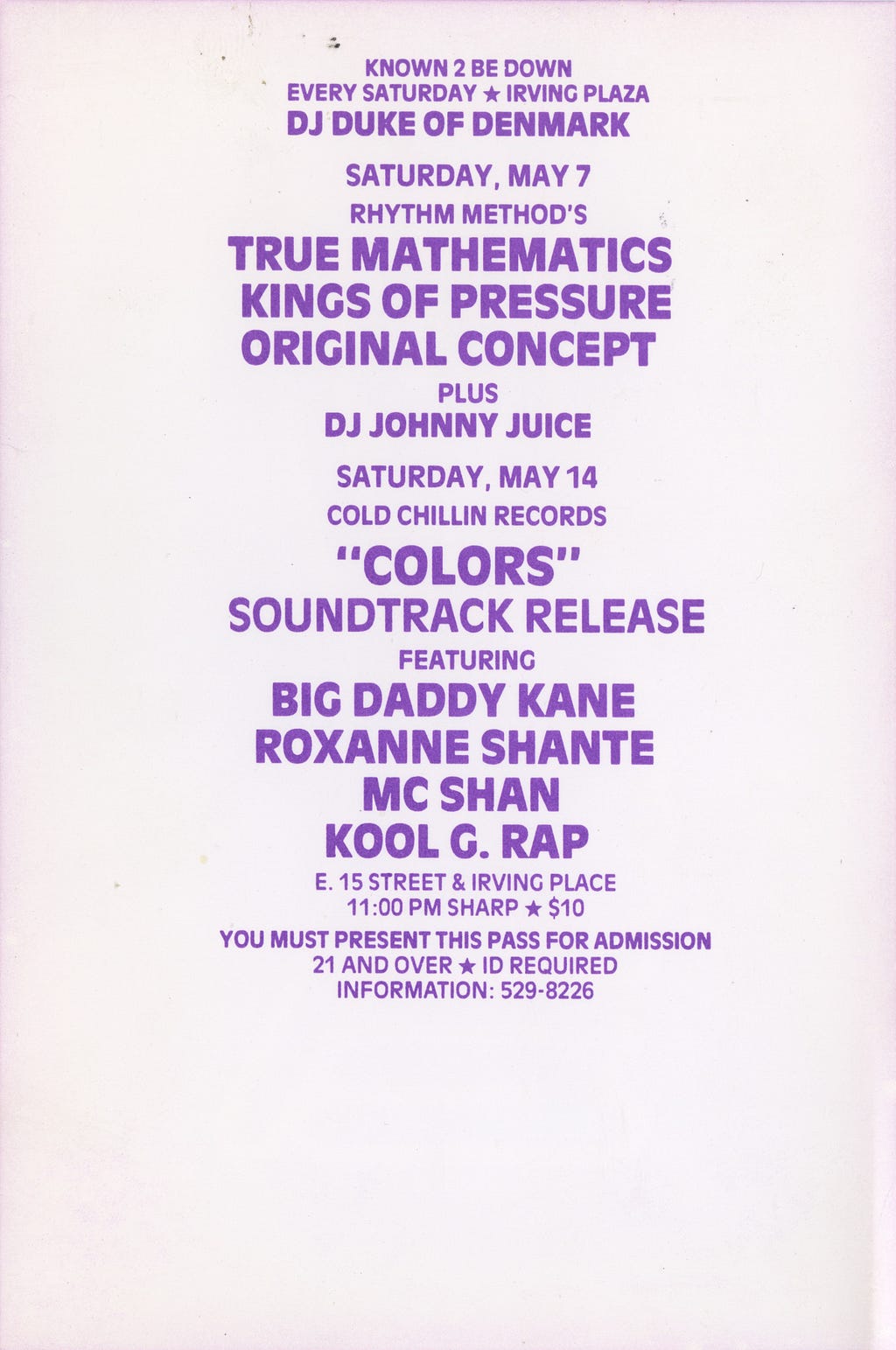

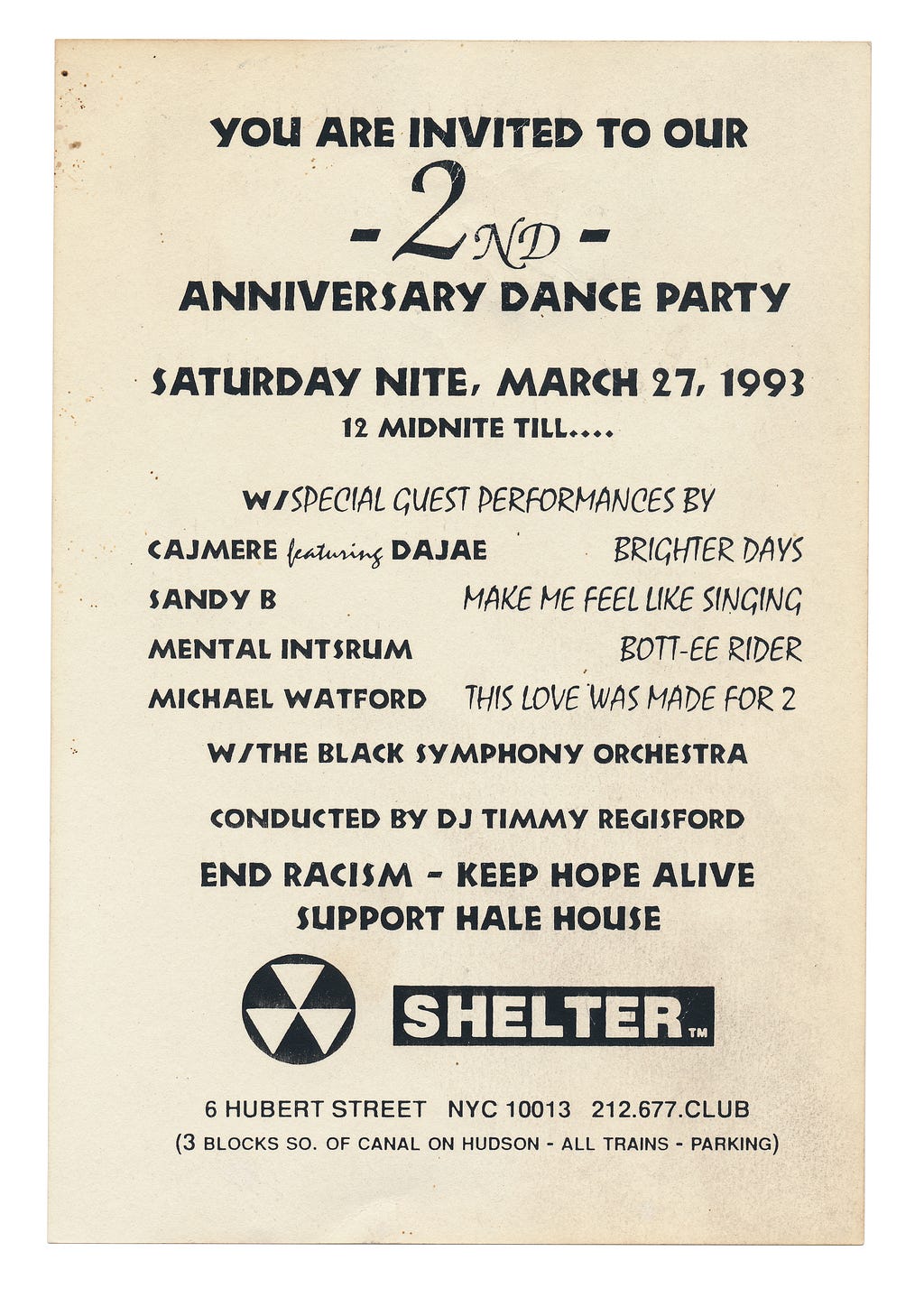

Club flyers, by design, were ephemeral objects distributed on street corners, outside of nightclubs and concert halls, in clothing stores and retail shops, and were not intended to be preserved for posterity. Through the 90s, they became both increasingly prevalent and more sophisticated as printing technology evolved. However with the advent of the internet, the flyer essentially disappeared overnight, despite it being common at one time for promoters to print thousands for any given event.

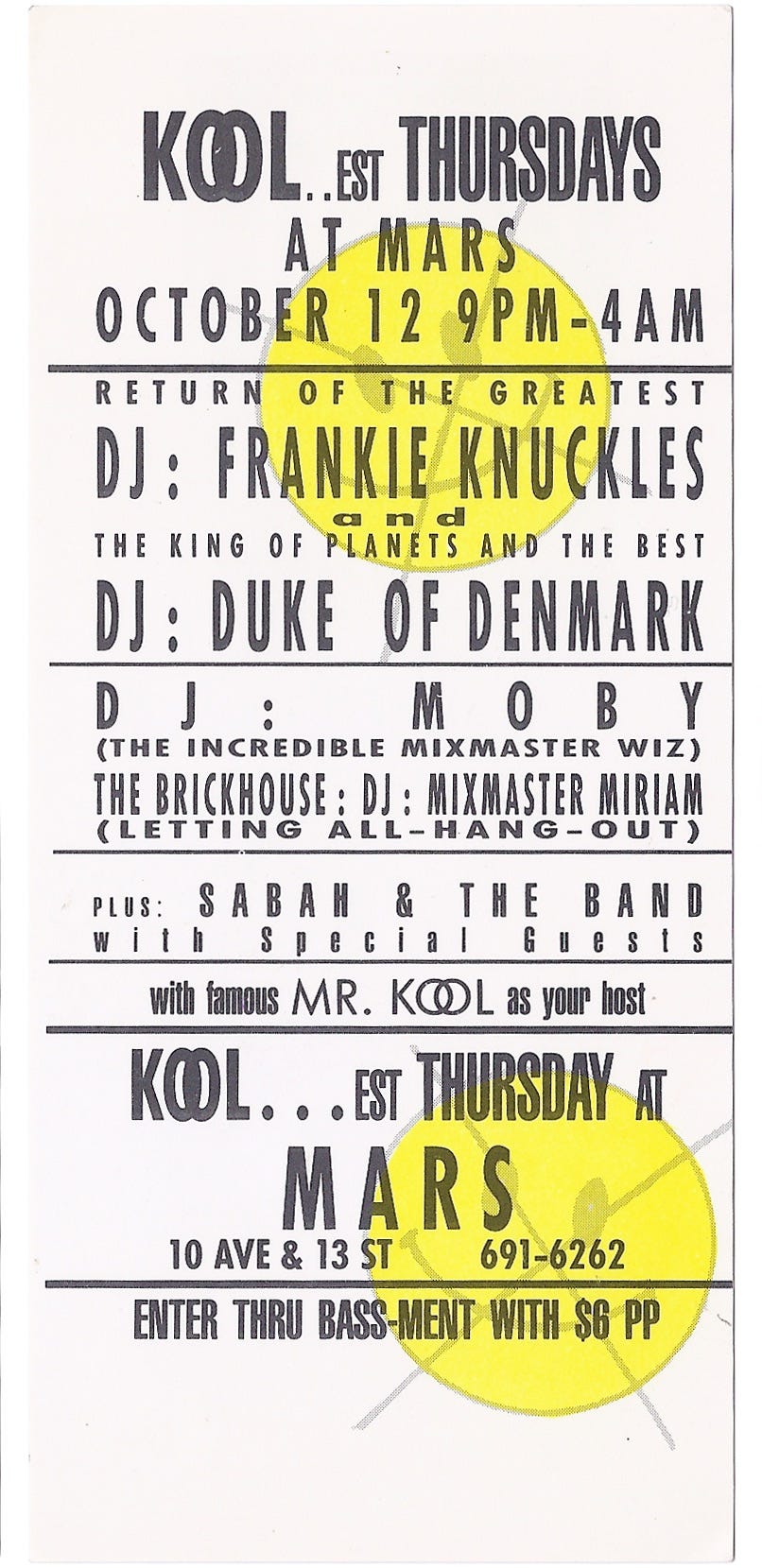

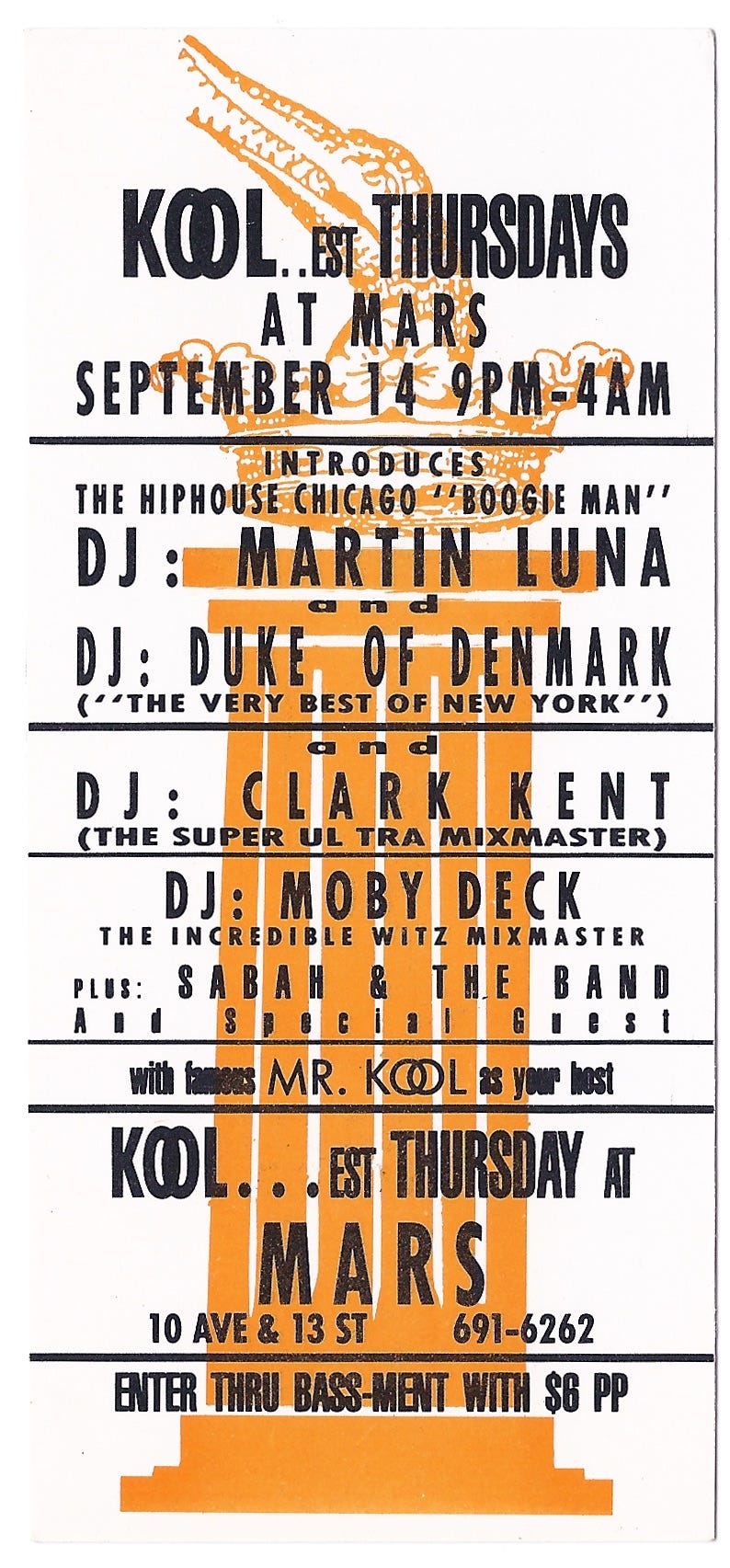

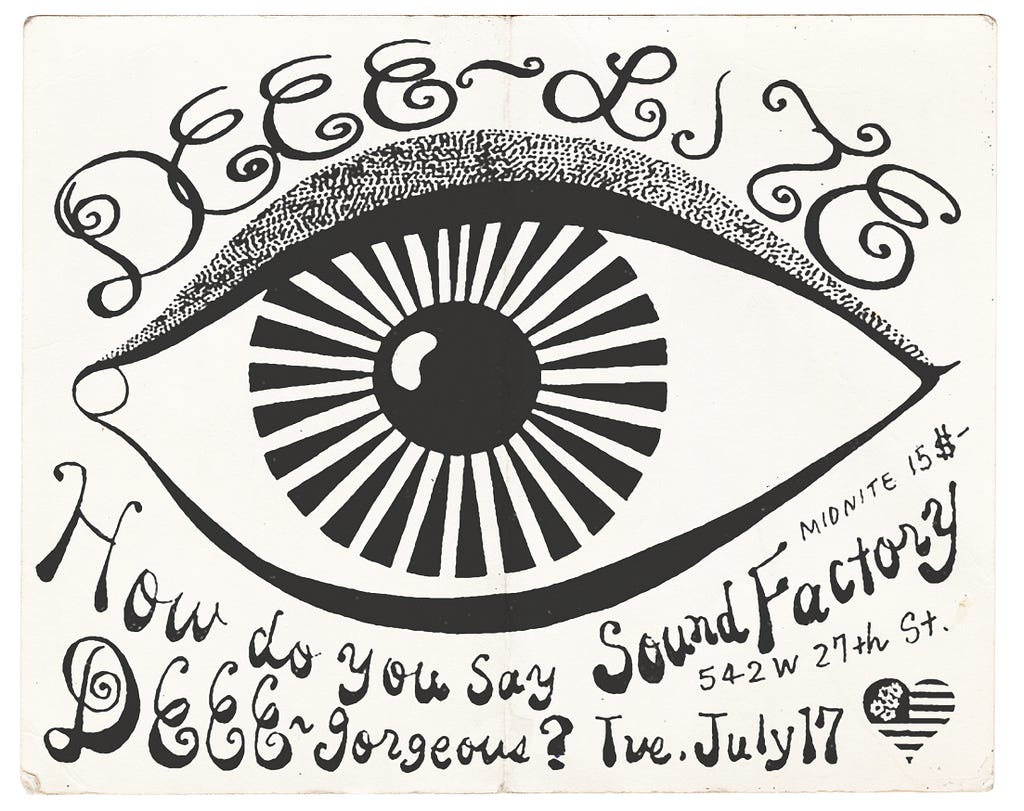

I asked some (famous) friends to write about these iconic pieces of art and the music and nightlife scenes they represent—including Mark Ronson, Moby, Nelson George, Frankie Inglese, Patrick Moxey and Lady Miss Kier of Deee-Lite. Below we’ve excerpted some choice images, words and memories to recapture an essential cultural moment.

So let’s take a trip back, back in time…

New York City, 1994. Fresh out my freshman year at Vassar College, I’d only been DJing about a year but I was already getting decent gigs that summer — house parties, hip-hop open mic nights and more than a few not-entirely-cool bars around the Upper East Side. The venues didn’t matter to me. There was nothing in the world I enjoyed more than spinning records. To paraphrase Peter Venkman… no job was too small, no fee was too small.

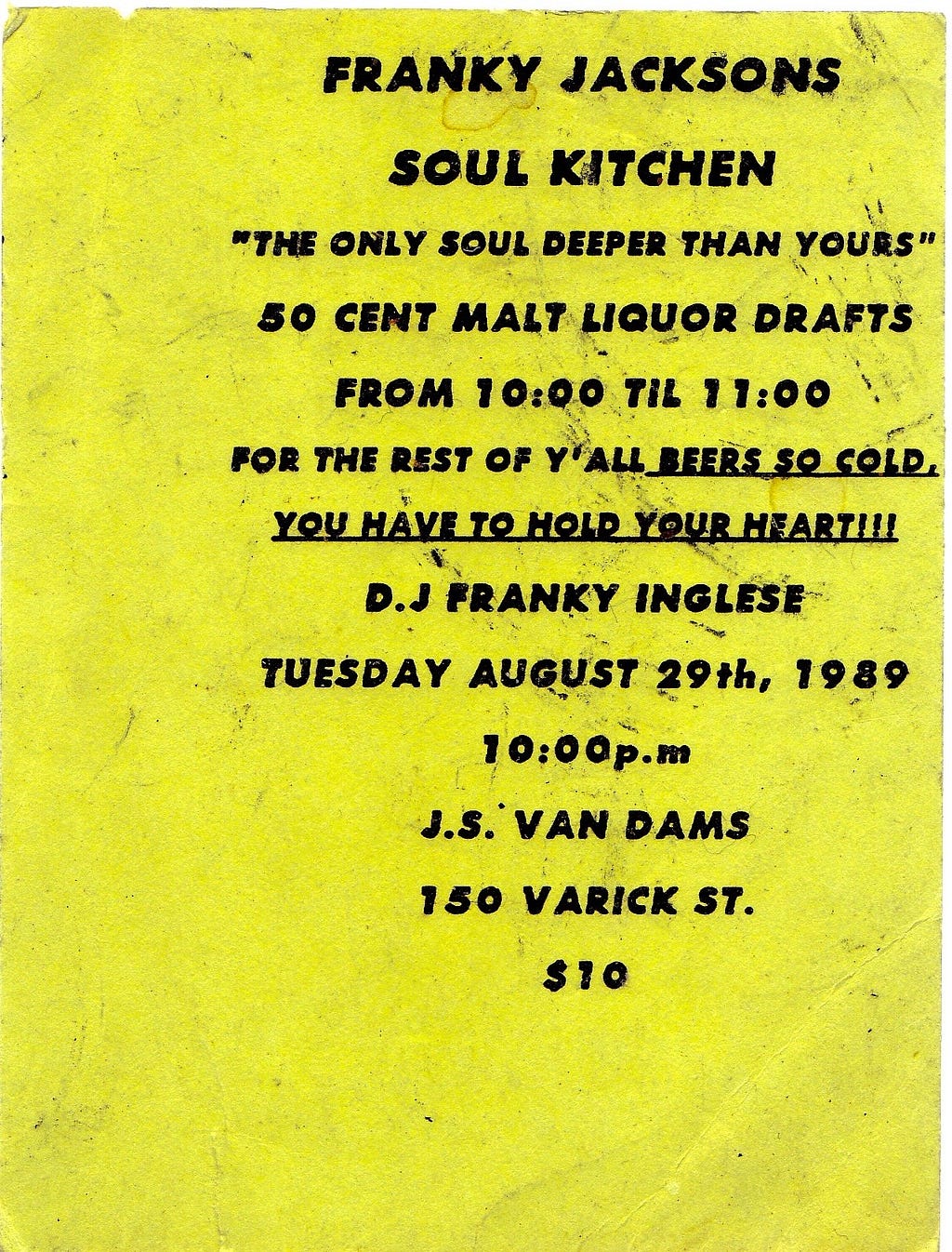

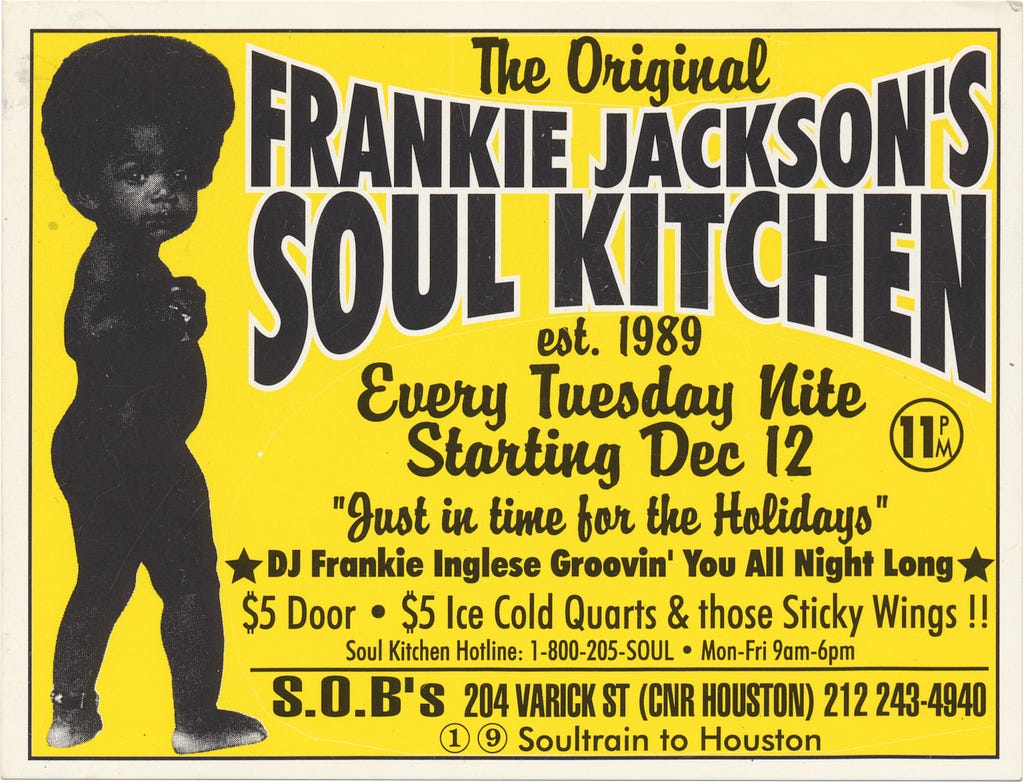

On my nights off, I went to parties like Giant Step & Soul Kitchen. Worlds apart from the venues I was playing, these were the holy grail of hip New York. They had the very best DJs (Stretch Armstrong, DJ Jules, DJ Enuff, DJ Hiro, Frankie Inglese) and the most beautiful array people (models, rap stars, ballers, art kids, skaters, drug dealers, etc.). The city had the hottest nights in what was then the global capital of nightlife. I may have fantasized about DJing at these clubs from time to time but I harbored no grand illusions that I’d be playing these places any time soon. I’m a pragmatist, however, and I armed myself with a strong supply of my own DJ demo tapes, on the off chance I was out and met a club owner who could potentially be a future employer.

On one such night while at Soul Kitchen, my high school pal Courtney introduced me to her new friend Carlos, who, along with his partner-in-nightlife Bill Spector threw the best hip-hop parties in all of downtown Manhattan, hands down! I saw my window of opportunity, gave Carlos the hard sell and handed him my tape, though I never expected to hear back. He and Bill had the best DJs in the city on rotation — they certainly didn’t need to give a gawky, teenage, no name a shot. So I was shocked when I got that call a few days later, asking if I wanted to play the opening slot at their new party the coming Friday.

I’ve put my brain through some wear and tear over the years and honestly have a hard time remembering names of places I played last week, but I will never forget the name and address of that party: Nut n’ Honey at Tilt, 179 Varick Street (corner of King Street, for extra credit). I remember the burnt orange ambience of the club lighting, how it was bathed in smoke. I remember how the Rane crossfader felt under my hand as I dropped Nice & Smooth’s “Old to the New.” I remember being thrilled to meet DJ Jules but trying to play it cool. And I remember going downstairs and hearing Stretch do a live blend of R. Kelly “Your Body’s Callin’” over the instrumental of Jeru’s “Come Clean” that blew my mind and had the main dance floor in a sweaty rhapsody. Damn, this really was it! It was going to be hard to go back to playing my other bumble-fuck gigs after having this taste of the high life.

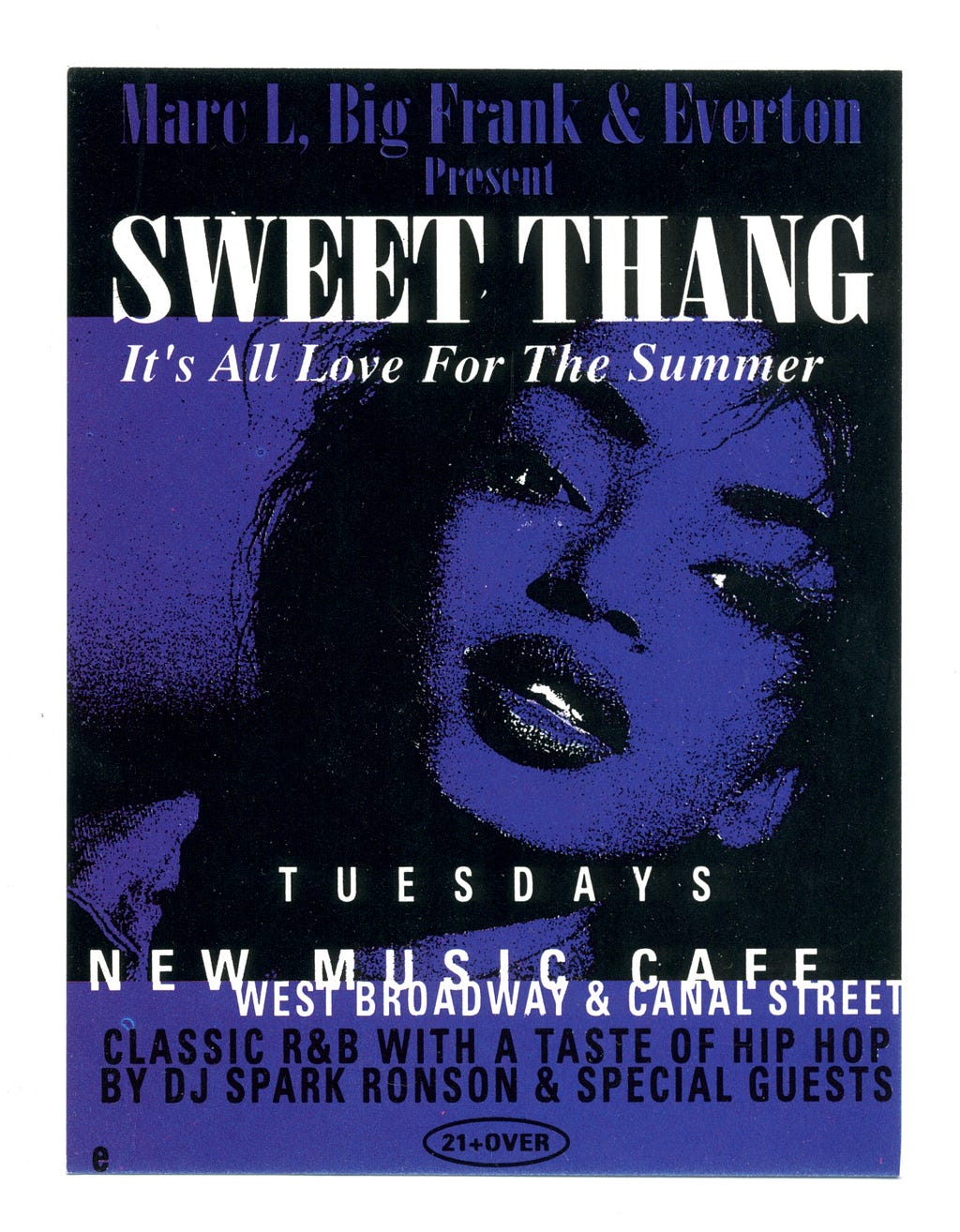

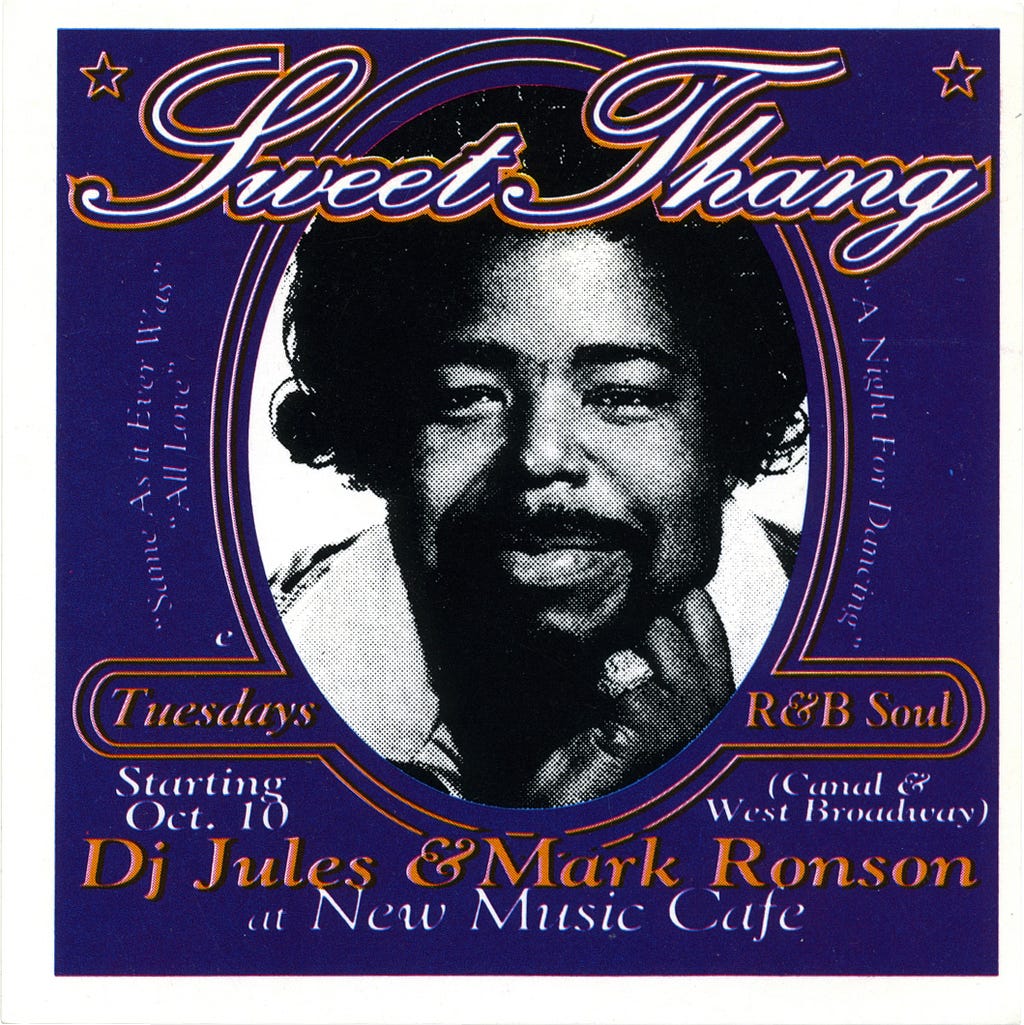

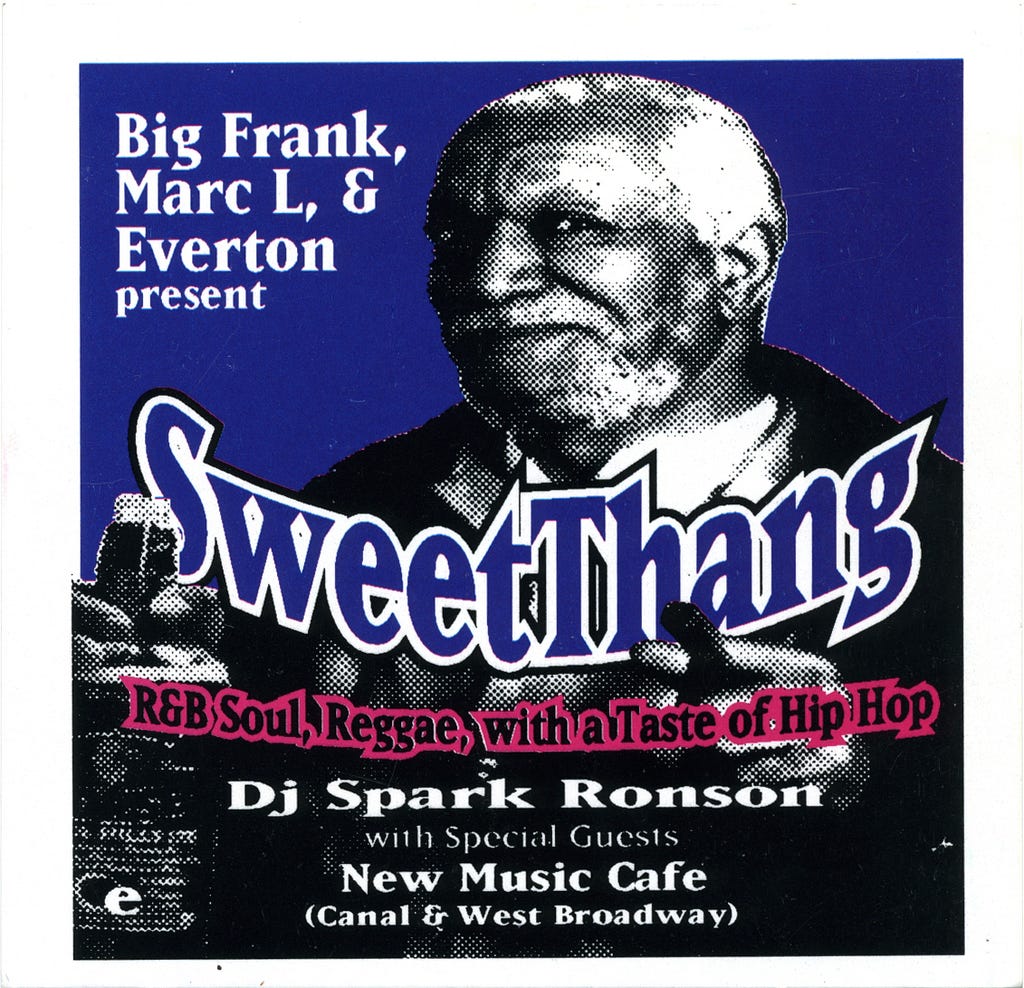

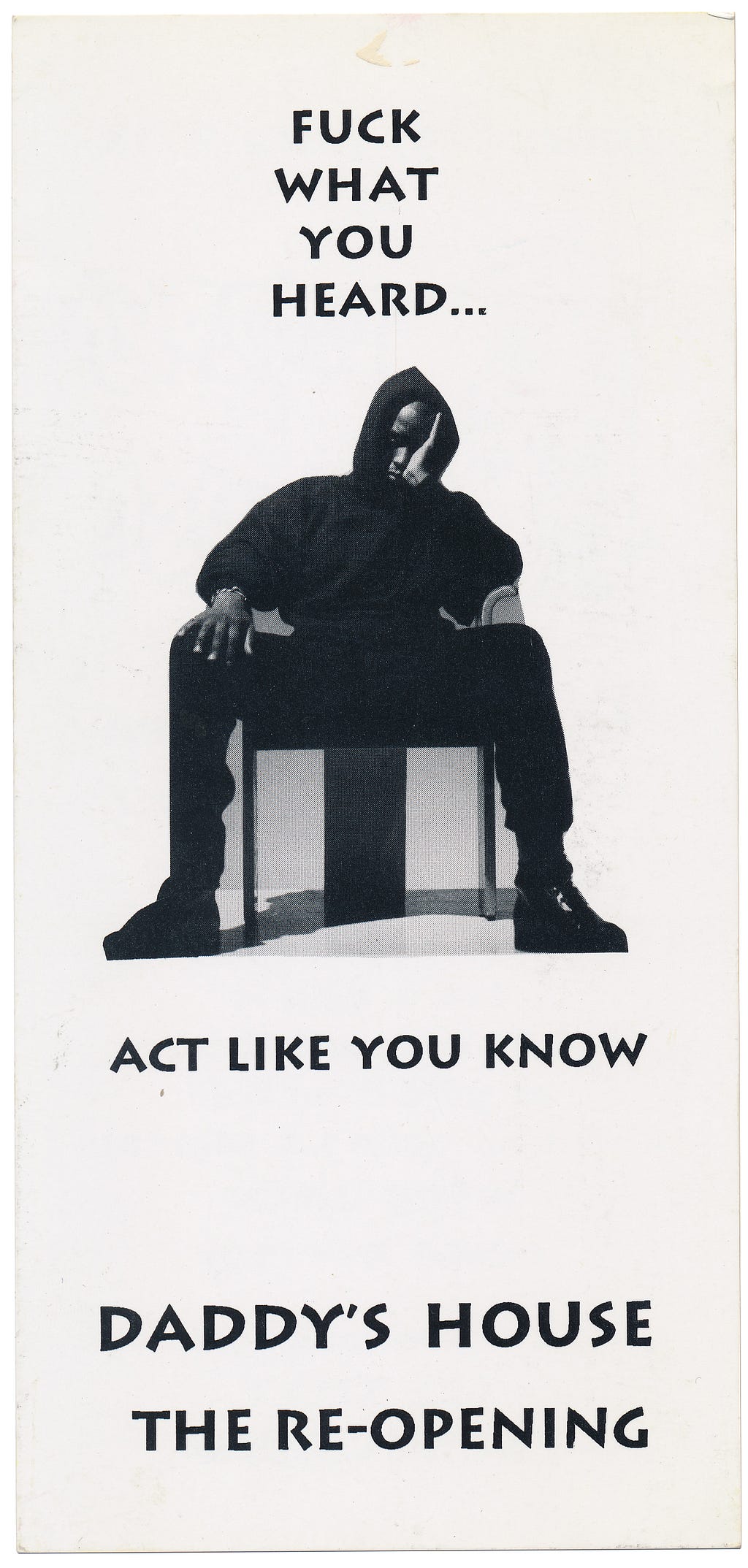

Luckily, I did a good job that night… plus, it probably didn’t hurt that I was cheap labor. Either way, I got a callback and after a few more gigs, I earned the coveted kudos of having my name on a flyer. I can’t overstate the importance of this; there, on a glossy piece of card was my name “Mark Ronson” printed right under “Stretch Armstrong,” maybe a few font sizes smaller but I didn’t care. Those flyers went everywhere. They were handed out by the hundreds on 14th Street and sat by the doors of Phat Farm, Supreme and Union. But still, it wasn’t the ego-stroke of “now the world will know my name!” It was the fact that it made it real. Before the internet, there weren’t many ways to prove your status unless you were legitimately famous. But this seal of approval sort of made me downtown famous — which was more than enough for me.

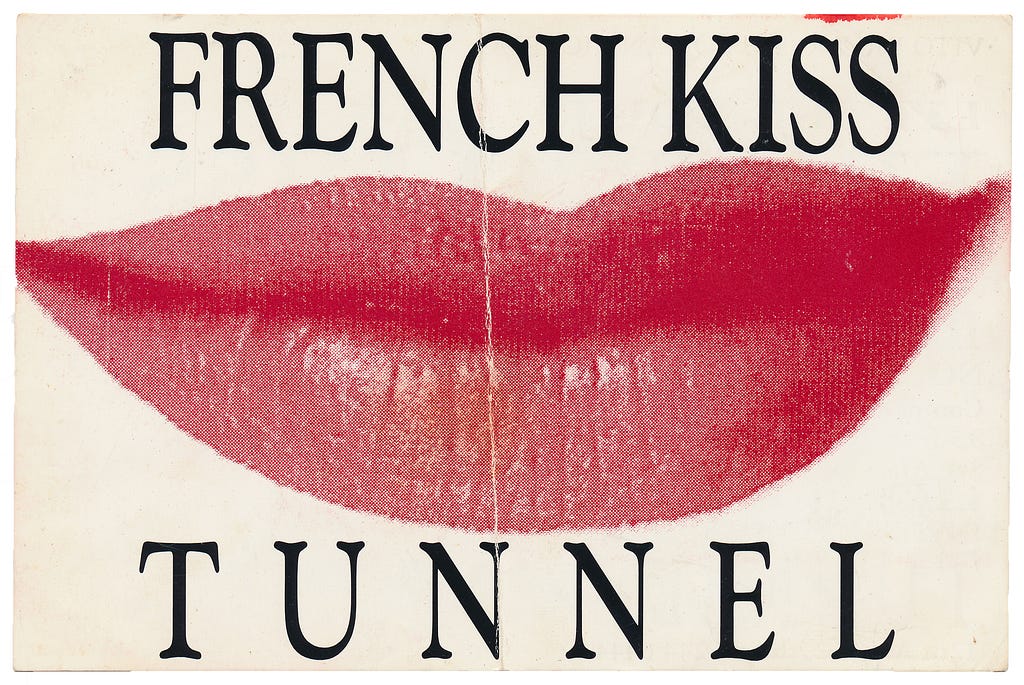

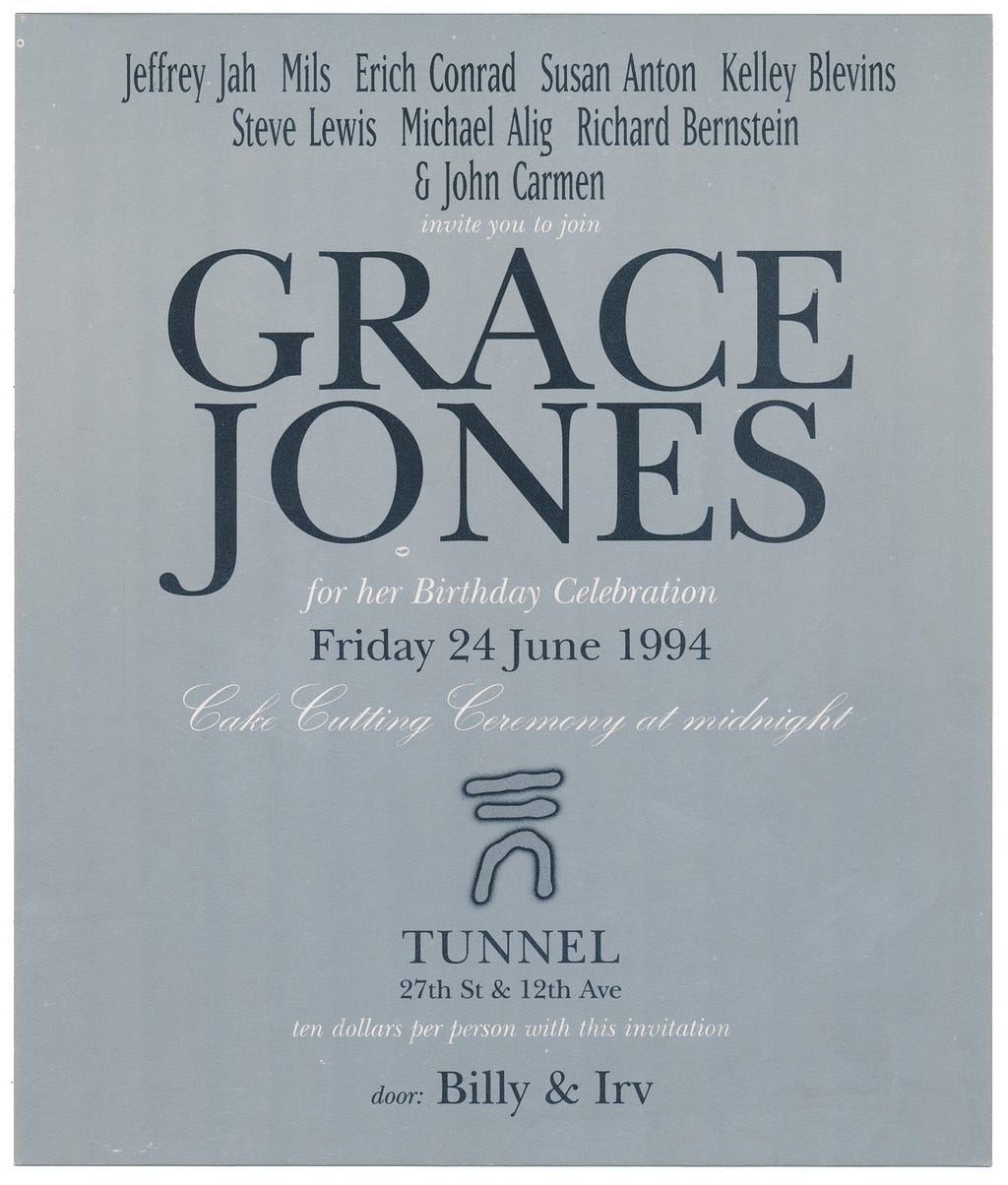

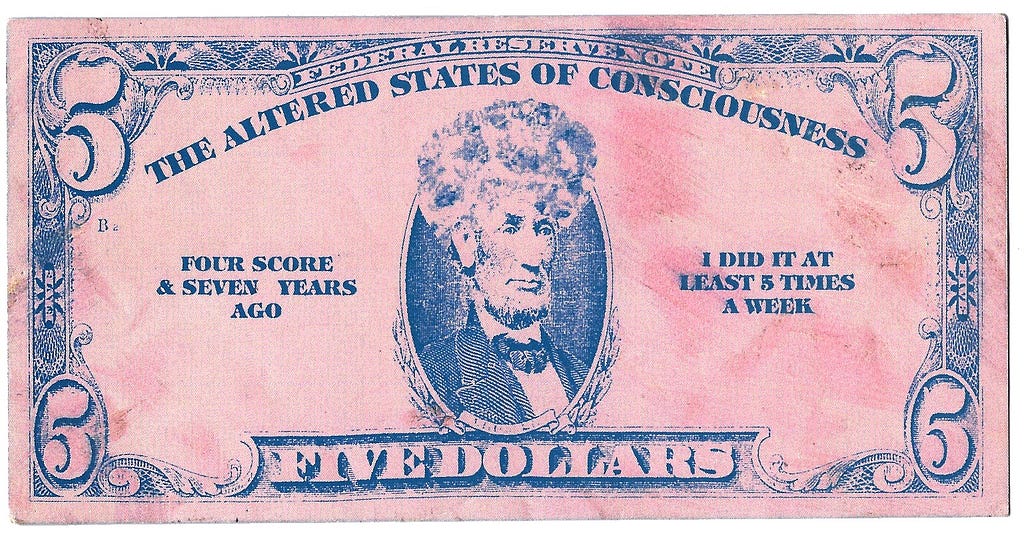

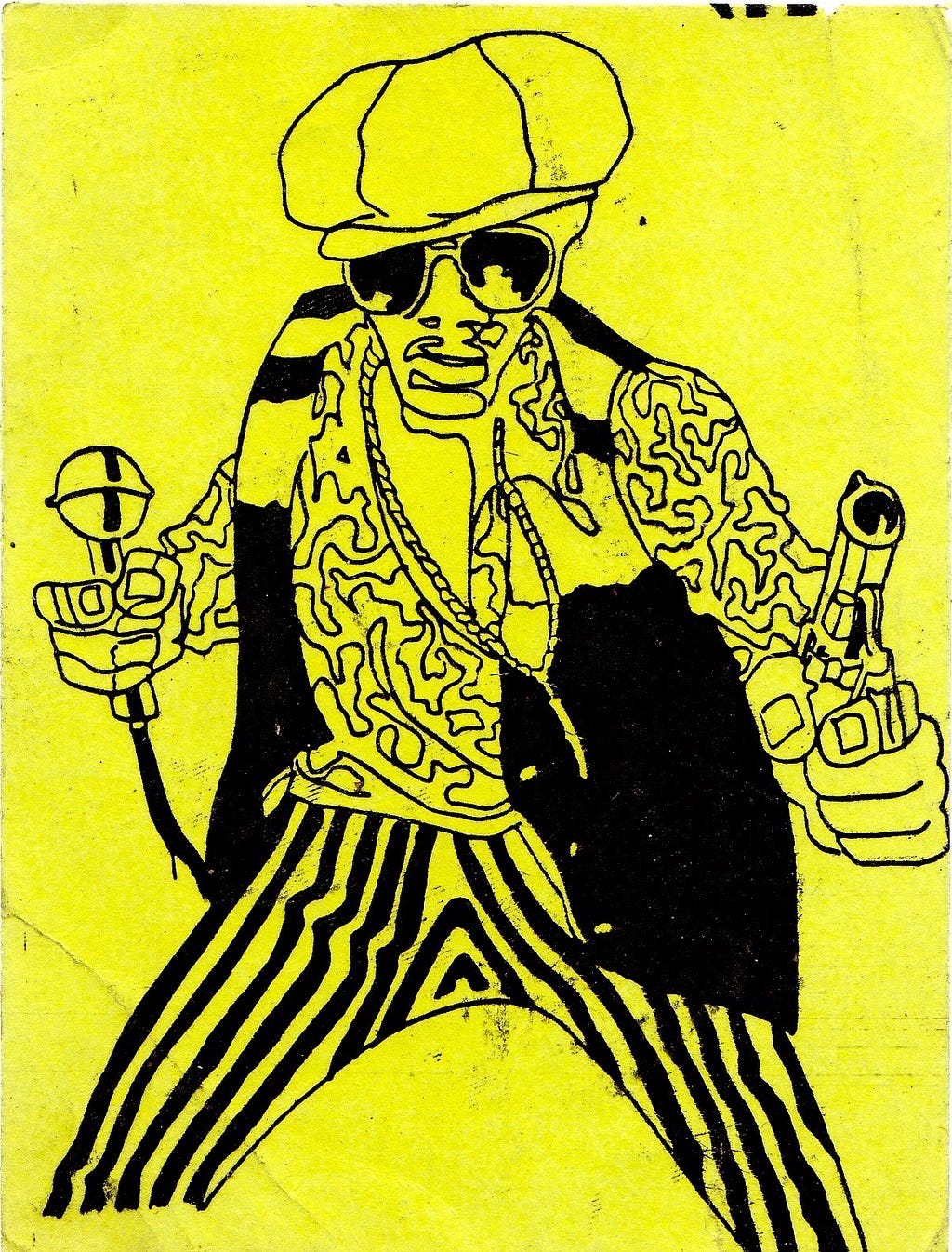

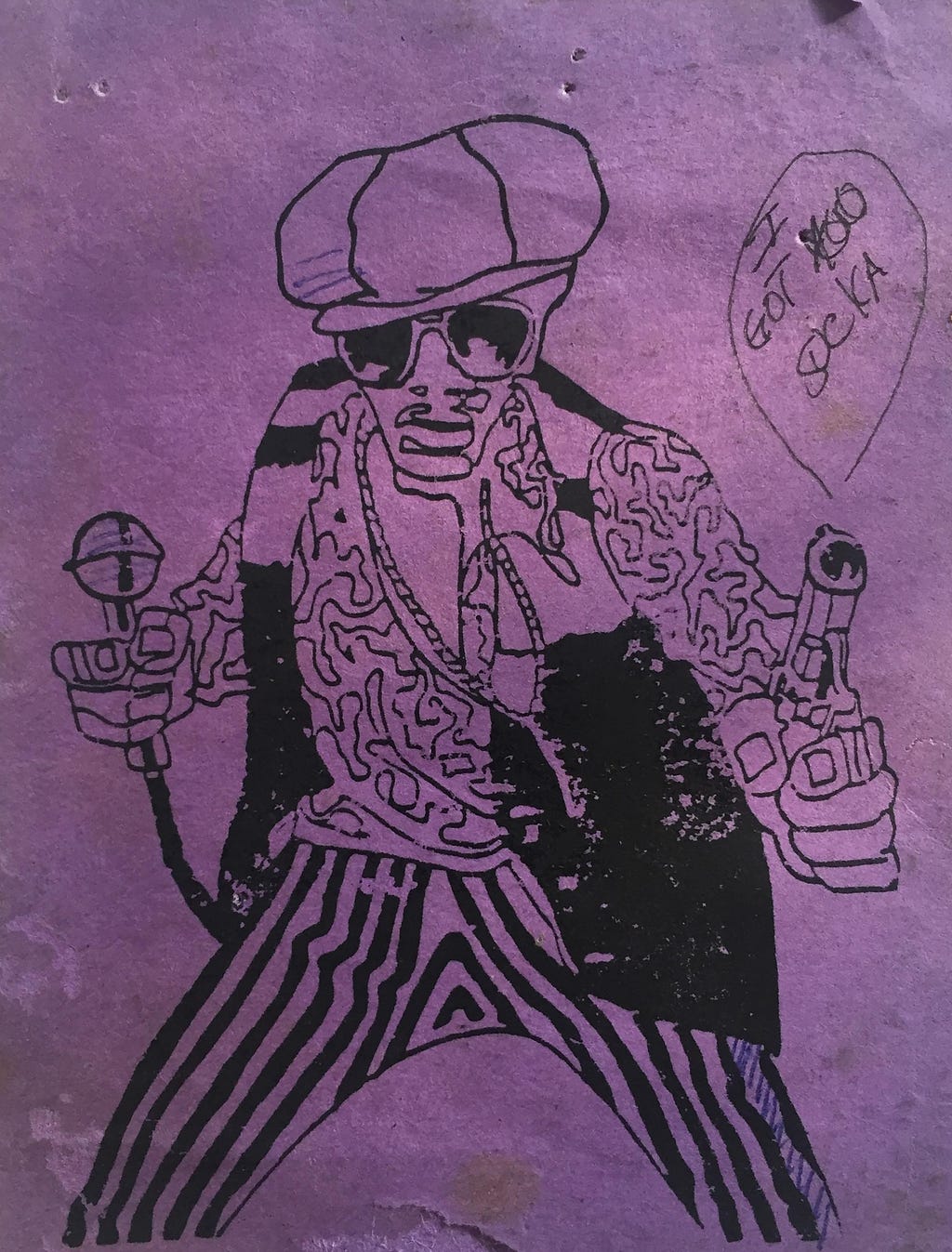

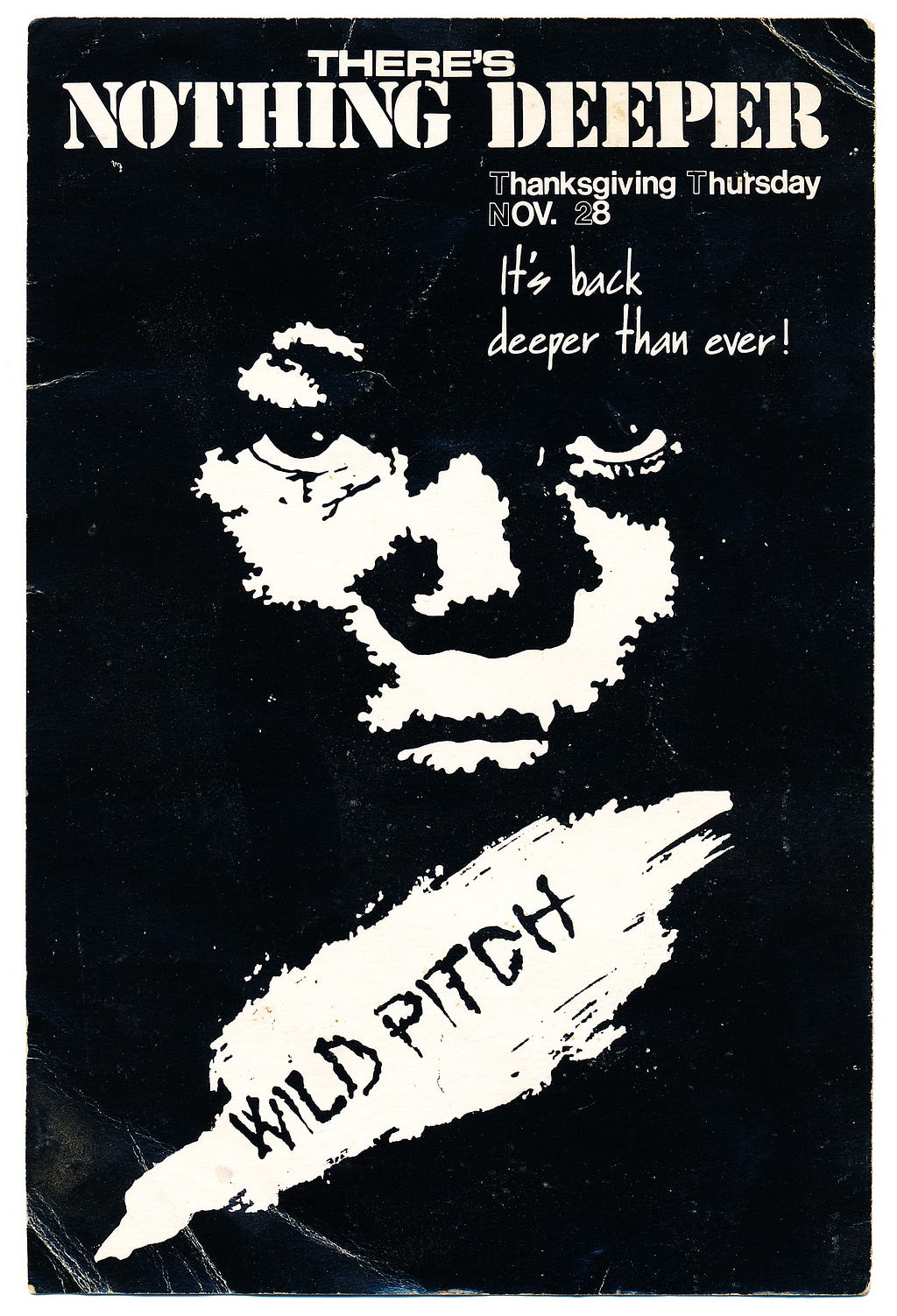

Through the coming years I held on to many of those flyers, snapshots of an amazing era in New York club history. A glorious time when people went to clubs pretty much strictly to enjoy the music, and whether rap, soul, disco, dancehall, house, boogie, R&B, the music was incredible! The flyers seemed themselves a physical manifestation of the evolution of New York’s downtown scene: the artwork could look born from a Basquiat 12-inch record sleeve: hand drawn, collagist and gorgeous. Or it could be as playful and eye-catching as Warhol’s pop art, flipping the script on some iconic image hoping to seize your attention as you walked by the window of a hip Soho boutique. When you look at a great club flyer, there’s a beauty in the economy of the design. There’s so much to say in so little space yet you could blow it up poster size and it’d look amazing on a gallery wall. A killer flyer didn’t guarantee a good party but you look at any flyer in this book and you can picture the great time being had.

In my mother’s house, among the many family photos in the living room, sits, inexplicably, a flyer from Sweet Thang (a Tuesday night party I DJed for several years) in a very nice sterling silver frame. It’s a simple royal blue, glossy card adorned with an image of a 70s era Barry White. I really have no idea how it’s endured there so long among the graduation photos, holiday snaps, etc. I imagine it’s not only for the good looking design, but more importantly for the fact that my mother knew how happy I was to be on the wheels in that club; how proud I was to have my name on that invite, and what a big part of my life that was. So it makes her happy to look at it, and that’s the sweet truth. Those flyers were so much more than just paper and cardboard.

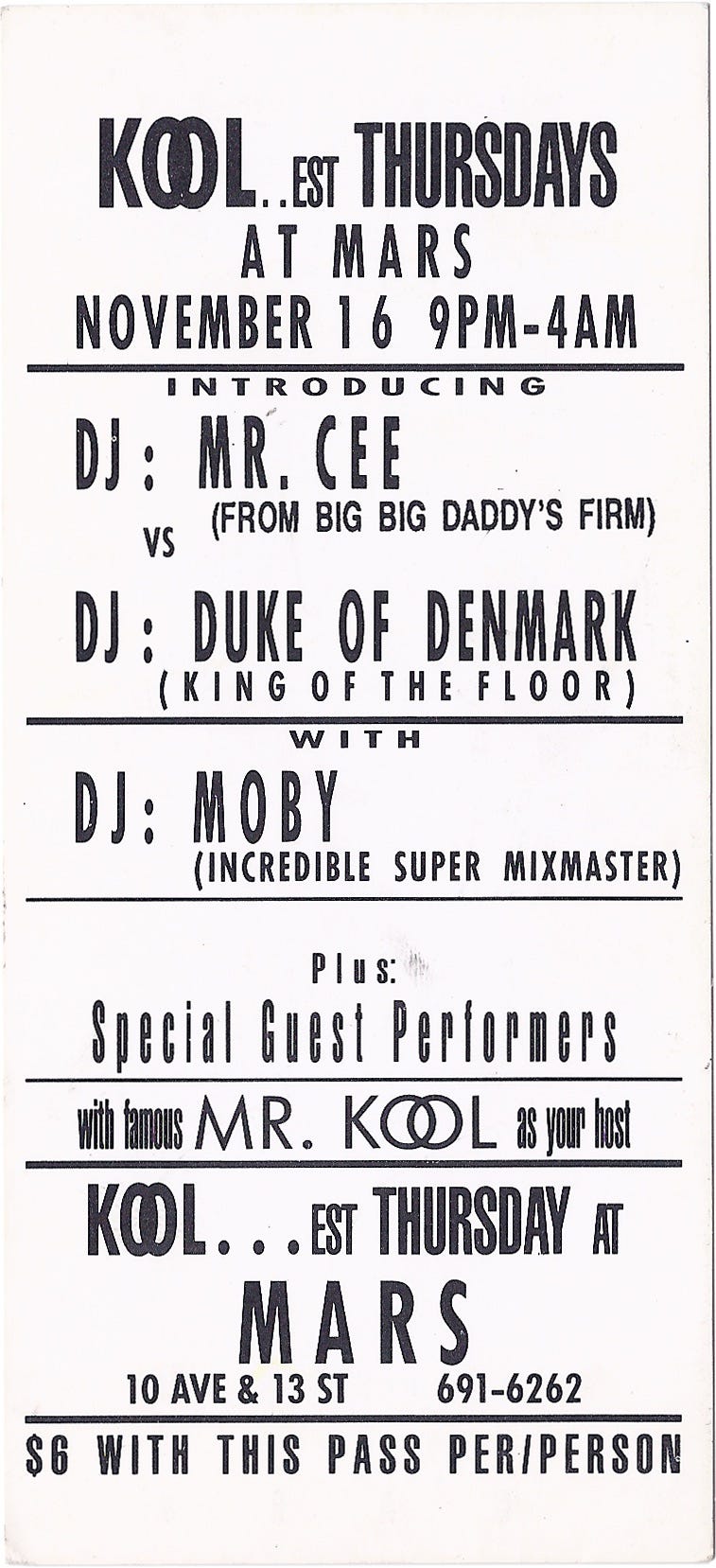

The first club I DJ’ed was Mars. I didn’t know that in order to get a job as a DJ you had to already be working as a DJ and be cool enough to know the people who were hiring them. Regardless, I ended up giving an employee from Mars a cassette which had hip-hop on one side and house music on the other, and somehow she gave it to the club director Yuki Watanabe who actually called me and gave me my first job as a DJ in the basement. That was what enabled me to move to NYC.

Mars was a remarkable nightclub. All the MCs at the time came through there — Run-DMC, A Tribe Called Quest, Ultramagnetic MCs, 3rd Bass, Big Daddy Kane. They all hung out there and would regularly get on the mic. Sad to say, but it was one of the last true melting pot nightclubs in NYC in terms of music, racial diversity, sexual orientation, where people came from and how much money they had. One of the biggest turning points in my life was getting that job.

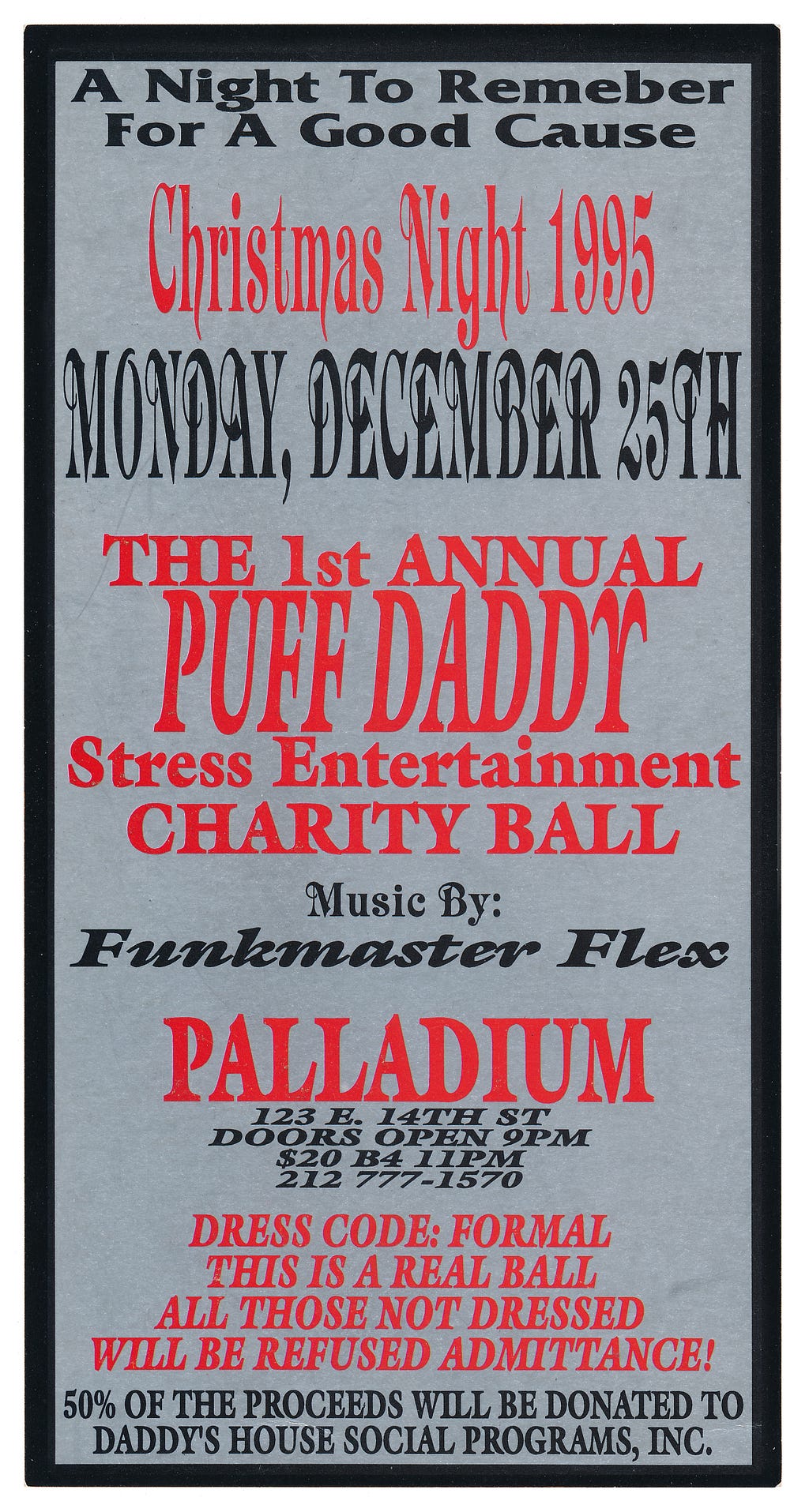

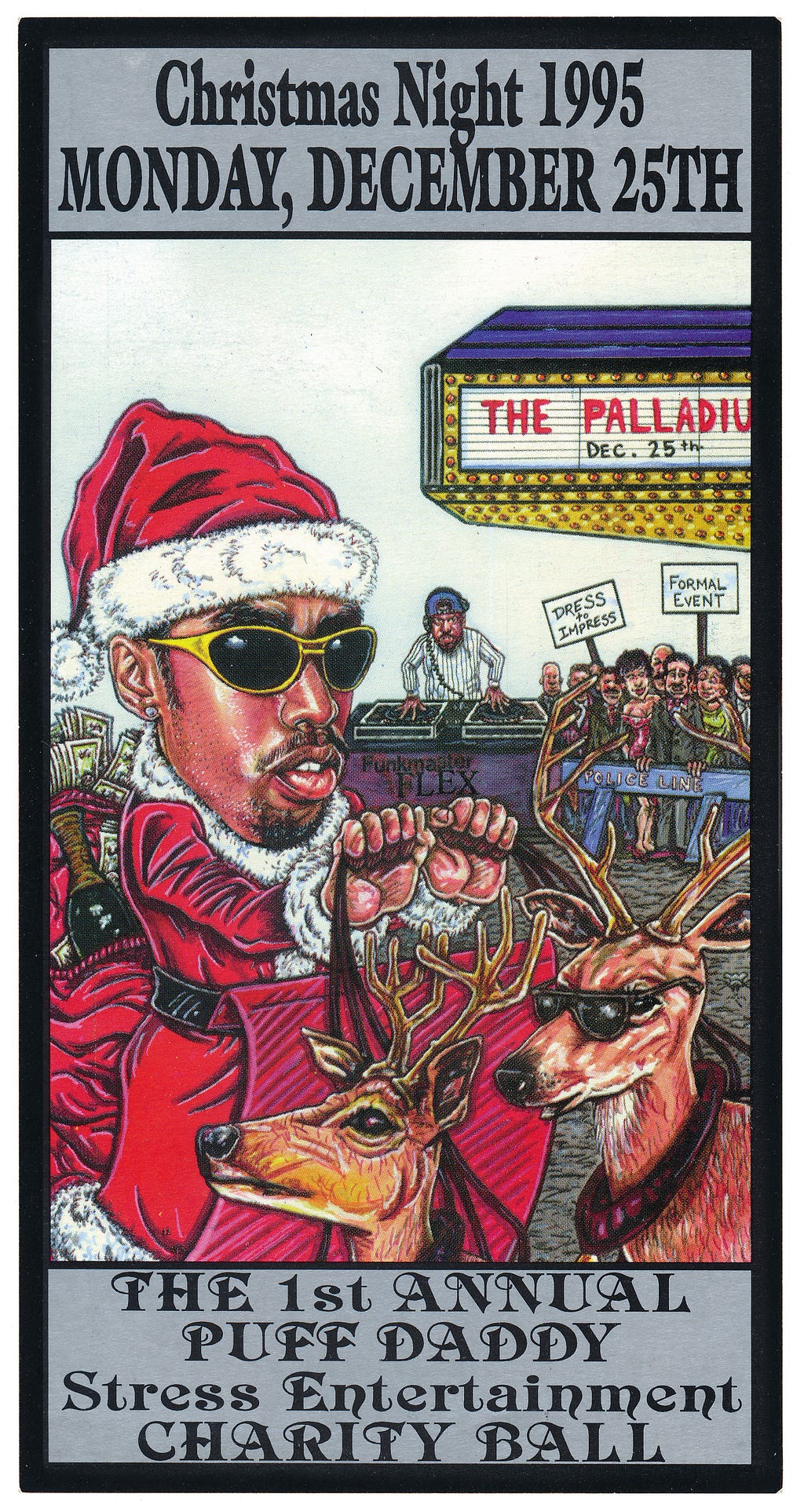

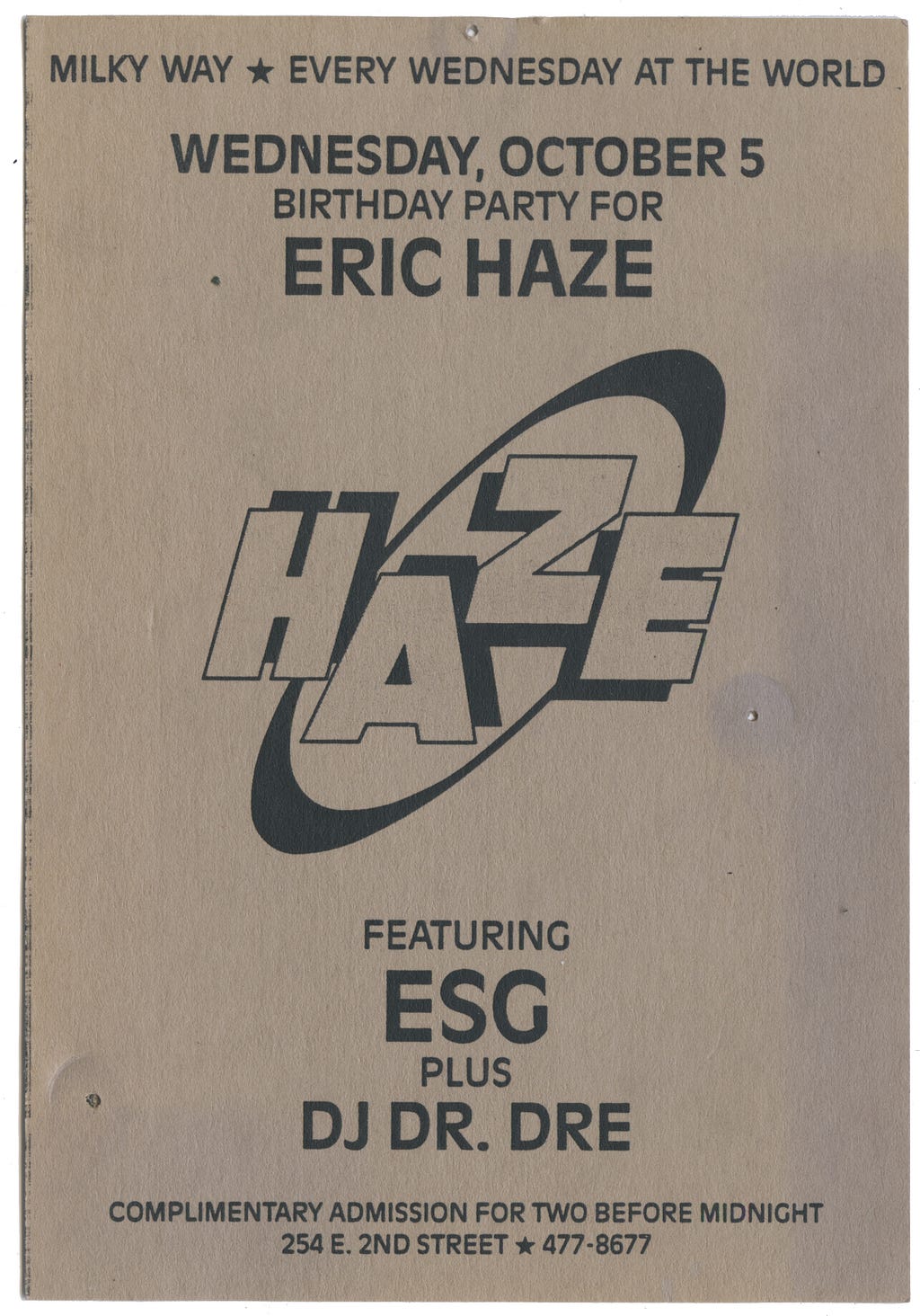

Looking through old flyers is to walk through a ghost town buried under high-rise condos, Starbucks and CVS stores, and remarkably anonymous 21st century architecture. Buried beneath them are clubs and parties that spoke for a wilder, more reckless and innovative city than the one we live in now. I walk up Crosby Street these days past posh new hotels and boutiques having forgotten that at 116 and 160 were parties I attended. The grimy The World on East 2nd Street, the spacious Building on 26th Street (where I went to Powerhouse parties) and the spooky Palladium were all sites of fun for me. Of all these places only SOB’s has survived into this new era, a place where I met one my most beloved girlfriends and saw Kanye West for the first time, reasons enough I hope it can survive this new, more buttoned down NYC.

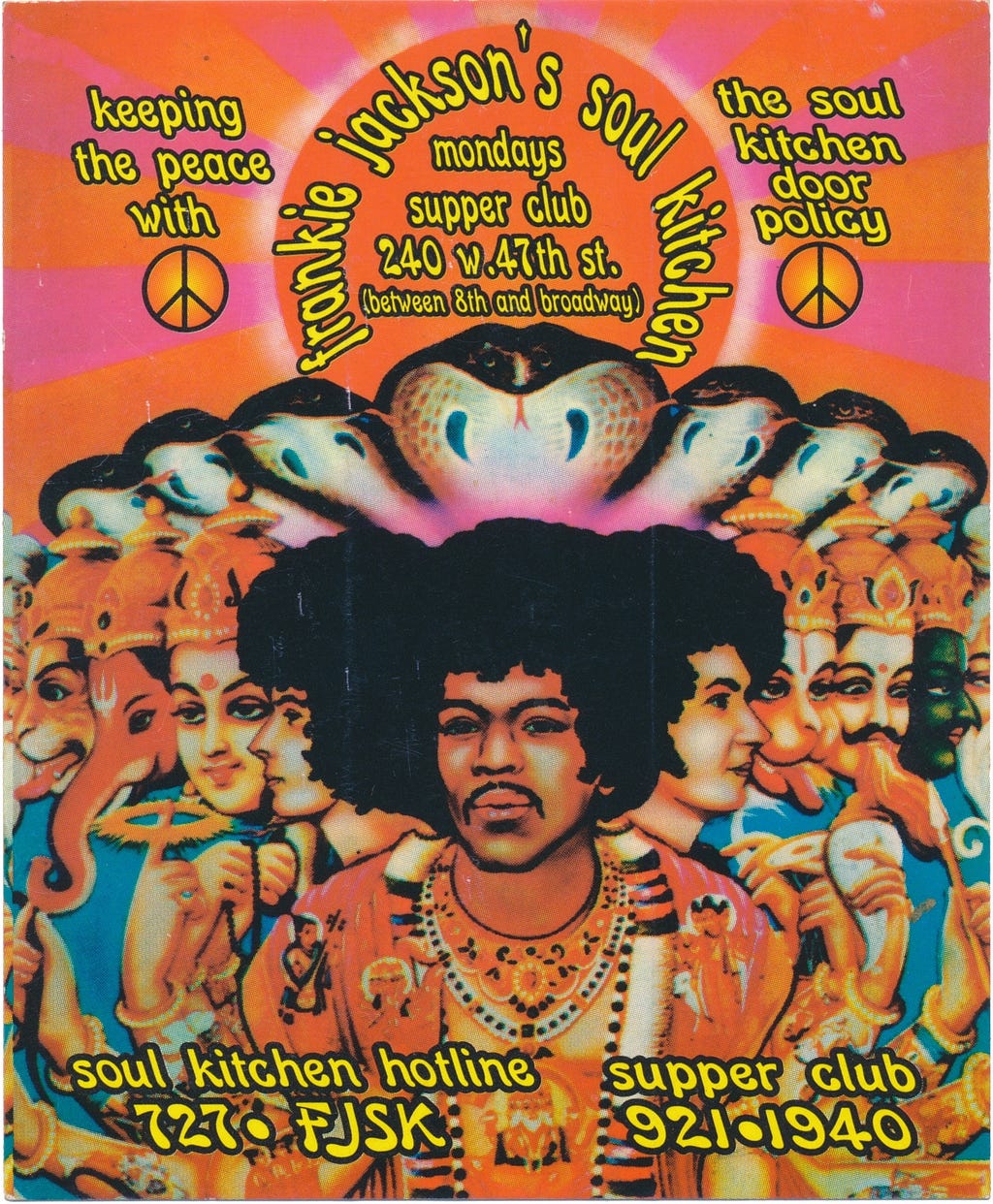

Soul Kitchen came about ’cause even though I was playing new music at Nell’s — house and hip-hop — I was also playing playing funk, soul and disco, but wanted to to do something where I could just play those records out, exclusively and in their entirety. One of our first spots was Brother’s Barbecue — our dream place, ’cause it was a soul restaurant and was small. We brought in a shitty sound system and set it up in the back, and it just took off from there. We went from Brother’s, where we had like 50 people, to 1,500 people plus, with crowds lined down the street to get it.

The original flyers were Kinkos Xeroxes on card stock. We’d cut ’em with those Slingline papercutters and hand ’em out at Mars and other spots. Jack did the earliest flyers. They’re so emblematic of that time — no computers, totally DIY. Later, with early Photoshop, I’d find an image and my man Richie would work on it on a computer which we’d rent by the hour, and then we’d take the design to a print shop. The design would be on a big floppy disc! It was a whole experience, making those early flyers. The first couple of years we handed them out ourselves.

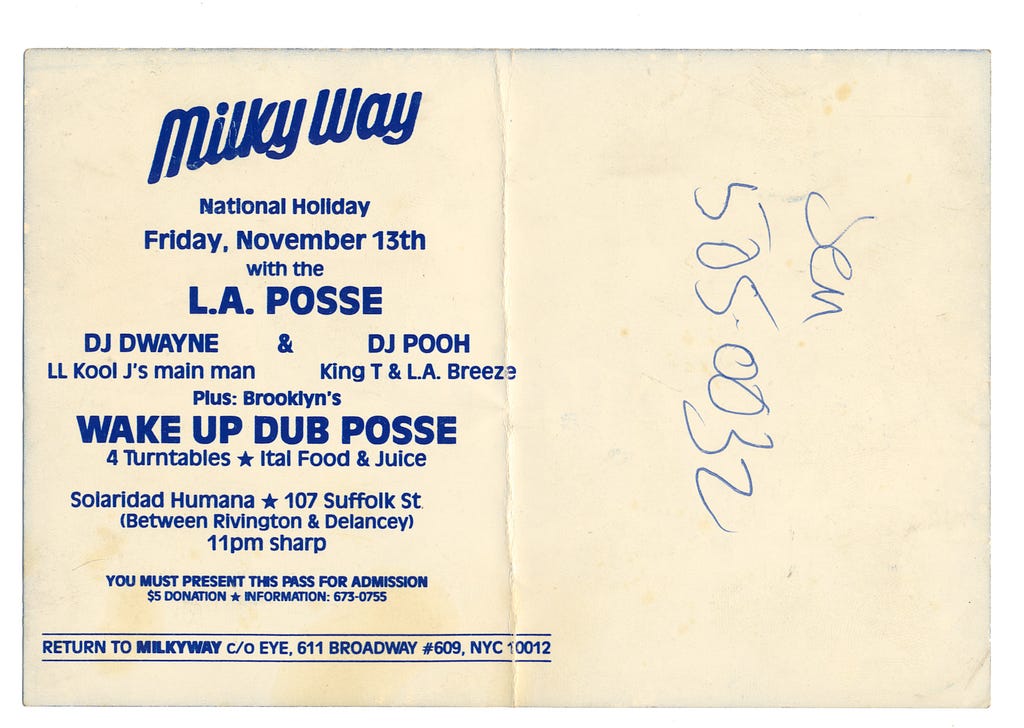

One of the first jobs I could get in the scene was as assistant cashier at Milky Way. My first night was an after party for the Beastie Boys when they opened for Run-DMC at Madison Square Garden. It was on the rooftop of Cuando which was a school on 2nd Ave and Houston Street. Truly, the most amazing collection of people came to Milky Way — whether it was Keith Haring, or John Kennedy Jr. & Darryl Hannah slumming it or whether it was the Jungle Brothers or Russell and Lyor and Fab Five Freddy. As a kid who loved hip-hop and a big all around music fan, there was no barrier to meet these people because at night it was quite democratic — everyone got to meet everyone.

As time went on, I was going out to find new spaces for these parties. I would walk the streets of the Lower East Side for hours to find spaces like olive oil warehouses, Polish war veterans homes, El Salvadorian refugee centers; different places where we could throw the parties. In time, I became a partner in Milky Way.

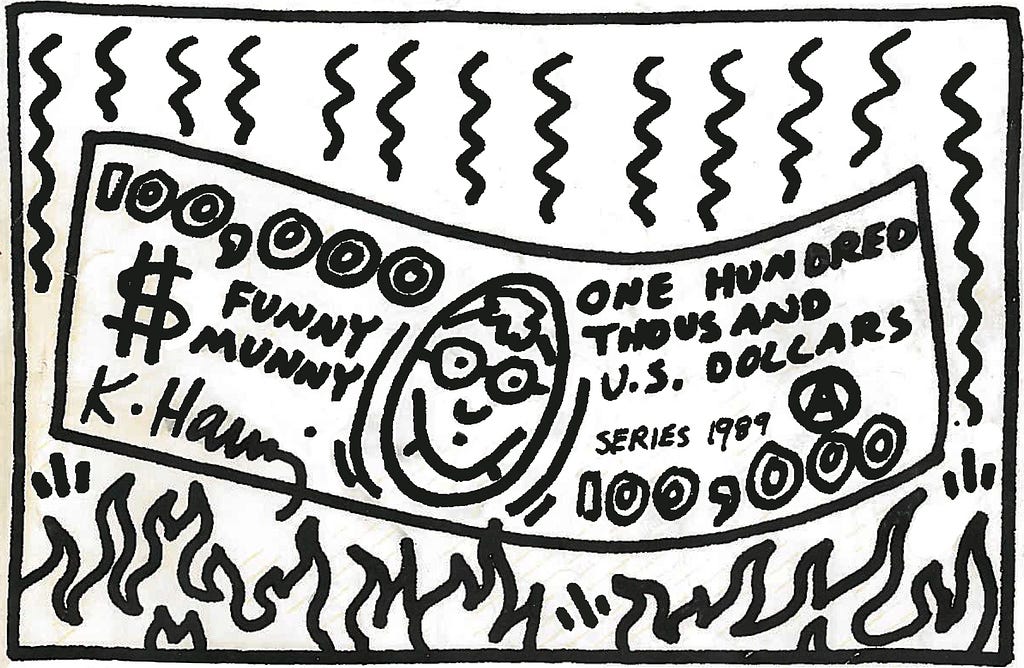

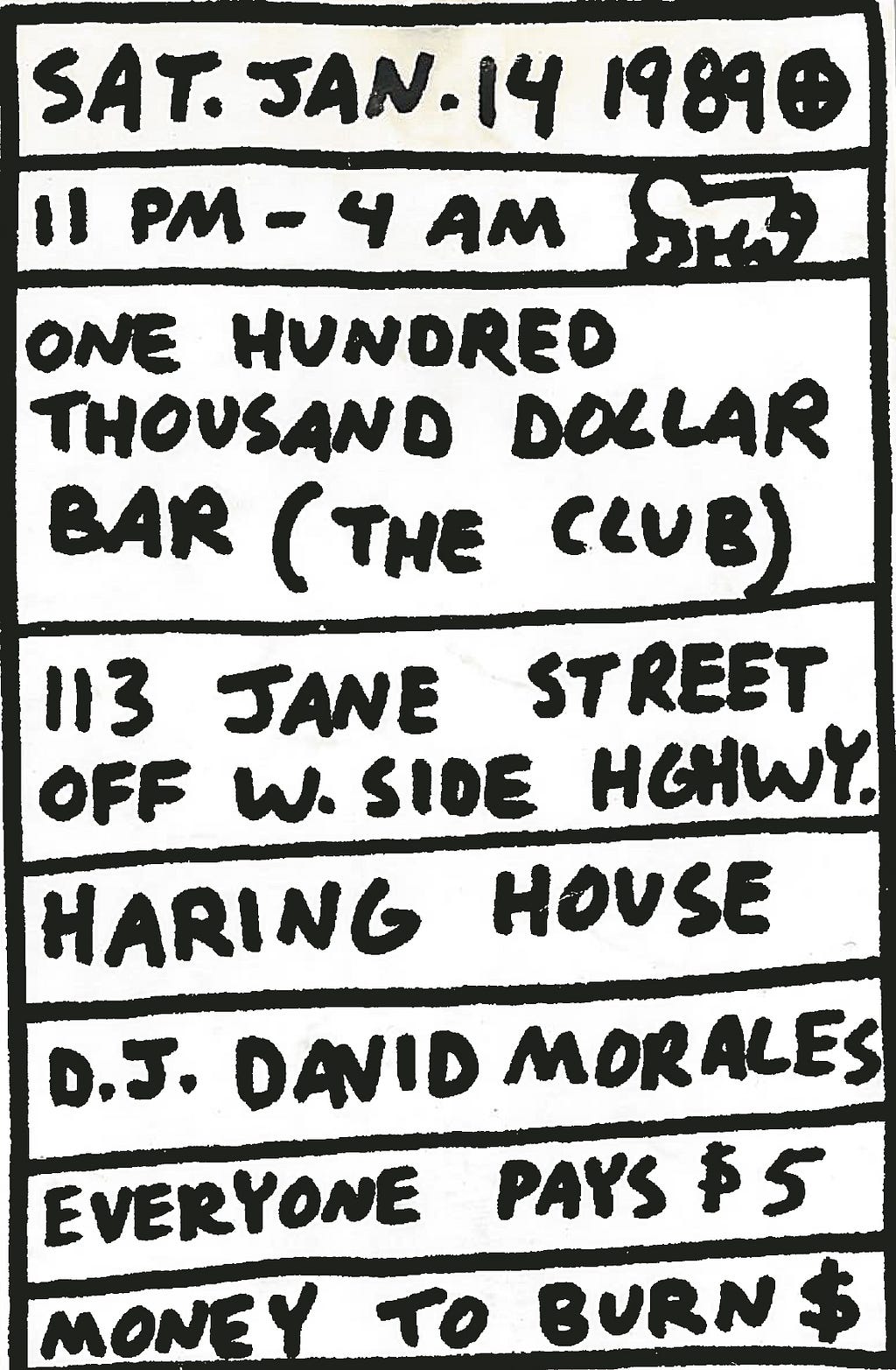

First we did Milky Way, then came PayDay—another hip-hop night and then Saturday night was our house night, $100,000 Bar, for which Keith Haring did the flyer. We did the first shows for Rob Base, De La Soul—we brought in the West Coast with N.W.A and Schoolly D came up from Philadelphia. It was a mixing of lots of artists—visual artists, graphic designers, video artists, music people, fashion people, etc.

On the west side of Manhattan, where all the new condos are now—that’s where all the old print shops used to be. We would put a telephone number on a flyer, and we have an answering machine and on the day before the party we would put the address on the outgoing message. So we had to have flyers, and you had to call the number to get the address. That’s how you knew where the party was. That’s how we made sure that the people we wanted to be there were there, and the people we didn’t want to be there wouldn’t be. It wasn’t just about the law. After a few weeks at the same location (if we stayed at the same location) we picked up more and more people who would hear about it, and then the parties would get out of control. When we moved locations, we were able to tell the people who we REALLY wanted to be there and get it back to the core group.

I’d be on the streets for hours talking to people — “can I throw a party here?” “Can I load in sound equipment?” “Can I do this, can I do that?” We faced a lot of challenges. One of the biggest was at this olive oil warehouse in Tribeca with no working elevator. We had to bring 20,000 pounds of sound equipment up five flights of stairs to throw the party and then bring it down the next day.

Thursdays at The World were a memorable night that will always warm my heart. Upstairs, Frankie Knuckles would play a stomping house set to a predominantly gay, Black crowd while downstaits, Dmitry played mix of house and hip-hop which drew a straighter crowd… but everybody mixed between these two rooms once they got to the club.

I would drive Dmitry to work and usually dance all night. His sets were eight hours and he usually DJ’ed five nights a week. The World, like many NYC clubs, was a place for the mafia to launder drug and prostitution money, so the clubs didn’t need to make a profit, which is one reason the scene was so vibrant. The streets were grimy and the neighborhoods segregated but in the club world, we were integrated and drugs were not necessarily part of the experience. These were not pick-up clubs or bottle bars. The crowds really came to dance at a time when the music scene was electric.

Todd Terry, Backroom, Pal Joey, Masters at Work and Tony Humphries were some of my favorite producers that kept my feet itching to dance on most nights of the week. I was a waitress in the day or worked in the clubs as a bathroom attendant or coat checker. At The World we would see the latest house hits performed every week. The clubs made sure we got a DJ set AND a live show. I was lucky to see Paris Grey sing “Big Fun,” “Good Life” with Inner City (one of the first house hits) as well as Bas Noir, Jomanda, A Guy Called Gerald, Liz Torrez, Loleatta Holloway, Two Tons of Fun, and even XLR doing “Work It to the Bone.”

Excerpted from No Sleep: NYC Nightlife Flyers 1988–1999 by Adrian Bartos aka DJ Stretch Armstrong and Evan Auerbach, available now from powerHouse Books.

Purchase No Sleep at Amazon, Barnes & Noble, and other fine retailers.

If you enjoyed reading this, please click the ♥ below. This will help to share the story with others.

Follow Cuepoint: Twitter | Facebook

No Sleep: NYC Nightlife Flyers 1988 to 1999 was originally published in Cuepoint on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Powered by WPeMatico