Evolving from cassette to CD to .zip file to streamed playlist, the hip-hop mixtape has changed its format but not its spirit and intention: to showcase different artists and DJs, and to introduce new music to the streets. Although the mixtape rose to prominence in the 1990s, the concept dated from hip-hop’s dawn.

Like soundclash tapes from Jamaica, recordings immortalized key events and live sets, but it took time, money, and connections to locate them.

Providing opportunities for DJs to showcase their skills while introducing listeners to new music, mixtapes were collections of tracks mixed and recorded on cassettes. Kool Herc, Grandmaster Flash, and Afrika Bambaataa created and sold mixtapes when they were coming up, creating a foundation for definitive classics such as “The Adventures of Grandmaster Flash on the Wheels of Steel” and Bambaataa’s “Planet Rock.”

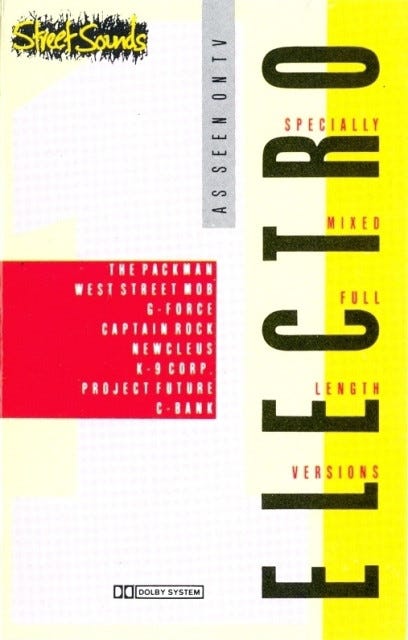

In 1983, London record company entrepreneur Morgan Khan issued the first of the soon-to-be classic Electro series on his StreetSounds label. These low-priced samplers, featuring the latest U.S. tracks mixed by various DJs, were issued on vinyl as well as cassette. The Electro albums were more than just compilations—they were effectively mixtapes between the U.K. audience and the early U.S. hip-hop movements. The series held biblical-like importance for any breakdance crew or hip-hop enthusiast across the U.K.

Thanks to the Electro albums, Run-D.M.C., BDP, Grandmaster Flash & the Furious Five, and Doug E. Fresh received widespread coverage; artists such as Ice-T, 2 Live Crew, Dr. Dre’s World Class Wreckin’ Cru, and Ice Cube’s C.I.A. were discovered in the U.K. years before they signed any kind of major label deal.

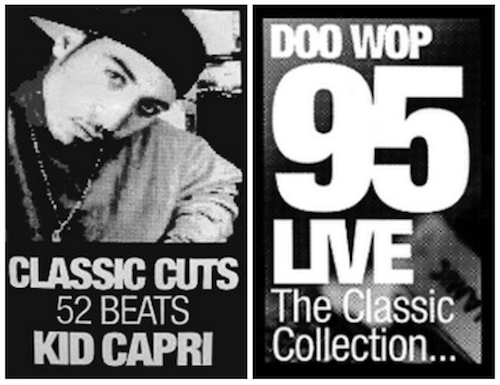

In the early 1990s, mixtapes became the soundtrack of the New York streets. Masters of the art such as Brucie B and Kid Capri paved the way, the latter dropping a classic called 52 Beats that cut up classic breaks. Ron G’s legendary mixtapes fused R&B and hip-hop blends, including exclusive freestyles from the likes of Biggie and Tupac. Among the biggest distributors were Tapemasters Inc. and Tape Kingz, who had direct links to the most renowned DJs.

Although there were hundreds of DJs in cycle, the mixtape game was a level playing field. It was survival of the hardest working. The DJs that got the exclusives, and mixed or marketed their product the best, won. Even though stores, DJs, and artists benefited from the exposure and financial returns, this was a highly illegal process. Stores were effectively selling bootleg material, unauthorized copies of intellectual property. Despite this, demand grew and DJs kept supplying that demand.

Hardcore hip-hop fans of technical skills revered the Crooklyn Cuts series by Premier, and the classic Rocks the Casbah mixtapes by DJ Spinbad pushed the parameters of creativity. Doo Wop served up the classic 95 Live (The Classic Collection) mixtape for heads who wanted to hear freestyles by their favorite artists.

Fans were constantly fiending for new material from the likes of Nas, Notorious B.I.G., Ja Rule, and Jay-Z… and Queens-native DJ Clue? had the right friends in high places to get the latest music. Walking around the streets of New York in 1994, it was impossible to ignore DJ Clue?’s voice blaring out of car stereos and stores. Canal Street in Manhattan, Fulton Street in Brooklyn and 125th Street in Harlem were lined with hundreds of vendors selling every kind of mixtape in existence, including Clue?’s catalogue.

Labels were victims of this piracy, but they also had to acknowledge that their artists were being discovered at an unprecedented rate. They couldn’t ignore the promotional opportunity that this presented for the artists that they had invested in. DJs had a direct line to the consumer: they circumvented the politics of daytime radio and the need for expensive music videos, and were a cost-effective A&R source. Some labels actually released their own mixtapes or deliberately leaked music to key mixtape DJs. Bad Boy released several mixtapes with DJ Clue?, Doo Wop, S&S, and Stretch Armstrong. Penalty Recordings released a mixtape with DJ Premier.

A new generation of DJs were back in the limelight. Bigger than ever thanks to the mixtape, they were self made, touring the world, and signing record contracts for official legal mixtapes. Loud Records — home to the Wu-Tang Clan, Mobb Deep, and Xzibit — signed Funkmaster Flex to a multi-album deal and commercially released four legitimate mixtapes. Tony Touch made history with his Power Cypha series — a collection of exclusive freestyles by key rappers. The 50 MCs edition was an epic feat that separated him from every other DJ. Tony Touch eventually signed a deal with Tommy Boy Records, and commercially released the first volume of The Piece Maker mixtape. Roc-A-Fella Records signed DJ Clue? to an exclusive deal, commercially releasing several editions of his Professional mixtape.

Towards the end of the decade, with the increased availability of CD writers, the mixtape made the transition to the compact disc. More DJs and more distributors meant more widespread availability, while a generation of graphic designers fueled a need for artwork that could compete with the creative department of any record label. Anything was fair game: freestyles, live clips, demos, unreleased material. As DJs competed to feed the streets at ever-faster rates, the standard of technical skills and mixing slowly diminished. It became more about DJs presenting the music. Kay Slay, Whoo Kid and, later, DJ Drama shouted out their trademark idents or taglines in their mixes, these becoming recognized as their seal of approval or co-sign.

The turning point for the mixtape industry came courtesy of Curtis Jackson. Although 50 Cent had previously signed to Columbia Records and released tracks such as “How to Rob” and “Rowdy Rowdy,” after an attempt on his life he was dropped from his label deal. His debut album Power of the Dollar was quietly released without any promotion and 50 was blackballed from the industry.

A victim of the streets and the music industry, 50 Cent used the mixtape market to return to the game and make his mark: 50 Cent Is the Future is a classic mixtape, thought to be one of the best of all time. 50 had his back against the wall and, together with Lloyd Banks and Tony Yayo from his G-Unit collective, he served up a collection of raw, audacious freestyles laid over other artists’ instrumentals to heat up the streets. It worked: his style and audacity caught the attention of the streets and created an immediate new fanbase. He was the underdog, the streets wanted to see him win and they wanted more music from him, as did Eminem and Dr. Dre.

An entire mixtape based on one artist’s music had not been done before. 50 Cent Is the Future was the ultimate showcase of 50’s uncompromising ability, free from any label or industry restraints, free of any pressure to appease the mainstream media.

The floodgates were open for artists to make their own mixtapes. They weren’t going to DJs for the exposure — 50 had shown artists how to do it for themselves. New artists used mixtapes to get noticed, whereas established artists used them to generate heat before their major label album dropped. Kanye West dropped the Get Well Soon mixtape over a year before The College Dropout appeared in 2004. Dipset released The Diplomats series of mixtapes; Fabolous unleashed More Street Dreams 2; Talib Kweli liberated The Beautiful Mix CD prior to dropping his album The Beautiful Struggle; and Consequence unveiled Take em’ to the Cleaners.

Brands began to commission and benefit from mixtapes. Kanye teamed with the Akademiks clothing brand for Jeanius Level Musik. Jay-Z’s The S. Carter Collection — his first and probably last mixtape — coincided with the launch of his Reebok ‘S. Carter’ shoe. Promo companies such as Cornerstone released monthly mixes with key DJs such as Premier, Jazzy Jeff, and Green Lantern, who paid attention to detail and employed real turntable skills.

As a DJ, producer, curator, and radio host, Green Lantern has set a standard that few can live up to. Working closely with new and established artists, he is the only DJ to have been recruited by Eminem, Jay-Z, and Nas for international tours, helping them rock crowds and advising them on set lists. Green Lantern has produced a vast number of classic mixtapes with precision and exemplary turntable techniques including the legendary Invasion Series with Eminem, The Champ Is Here with Jadakiss, and the N Word with Nas, which was a prelude to his controversial untitled album in 2008.

In 2006 DJ Drama had the southern hip-hop scene sewn up with his Gangsta Grillz series, but it was the Dedicated series with Lil Wayne that put him on the map. Drama worked closely with Wayne on the mixtape and created a new dynamic perception for an artist who was already a ten-year veteran within hip hop. DJ Drama was internationally known on the back of Dedication 2 and it helped stoke the flames of anticipation for Lil Wayne’s Carter III album. “I think in a lotta’ ways what me and Wayne did together has helped his growth, and helped him climb to where he is now,” DJ Drama said. “That’s what the Gangster Grillz brand is all about, so shout out to him, he’s doin’ his thing… I think he’s feeding the people, and I can understand that, since I call myself Mr Thanksgiving — you know that’s what I do, I feed the people, I feed the streets.”

In 2007, however, Drama became one of the few DJs to be arrested for selling mixtapes. Atlanta police raided his office and seized 81,000 CDs; Drama and his team were filmed by local TV news channels being taken into custody on charges of running a crime ring, bootlegging, and racketeering. “They took some equipment, they took some bank accounts, they took some hard drives,” he recalled. “But instead of waving a white flag, I went in and redid my whole album. Instead of worrying about the stuff they took, I went and bought me some new stuff. A lot of other artists came to my support, put my album back together, and I stand here right in front of you today.”

Drama has been credited with rejuvenating the careers of Lil Wayne, Young Jeezy, and many other artists. Labels were paying for him to produce and release mixtapes that presented a difficult dilemma for the RIAA (Recording Industry Association of America) and the police who were trying to charge him. DJ Drama never appeared in court and he hasn’t stopped releasing mixtapes.

In 2007, when Kanye West put Lil Wayne on his track “Barry Bonds,” it was official to anyone who didn’t already know that Lil Wayne was hot. “Man, he just gave so much material, just knocking out like so many mixtapes, so many freestyles, and just jumping on everything,” Kanye West recalled. “I just thought that was amazing, how many ill verses he had, like his voice, his whole movement. I feel like my album’s a time capsule of 2007, it’s also a classic, but it’s also one of those ones ‘Now this is what was going on in 2007…’”

The mixtape is a powerful, cost-effective way of introducing new music to potential new fans. People listen to them with the intent and expectation of discovering new music and artists. They have been the soundtrack to many lives.

Excerpted from Hip-Hop Raised Me by DJ Semtex, published by Thames & Hudson. Available now from Amazon, Barnes & Noble and other fine retailers.

Street Dreams: How Hip-Hop Mixtapes Changed the Game was originally published in Cuepoint on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Powered by WPeMatico