It is the site of the deadliest stateside disaster of World War II, an accidental explosion which killed hundreds of men — the majority of them black.

Yet the Port Chicago Naval Magazine National Memorial is the least visited site in the National Park Service’s system in the lower 48 states, even though it’s just an hour’s drive from San Francisco.

On the night of July 17, 1944, a massive explosion and fire tore through two ships and the pier. Of the 320 men killed instantly, 202 were African-American and many were just teenagers.

Among other things, the memorial is a reminder of the cost of segregation. After a small group of survivors took a principled stand against discrimination in the American military, the incident at Port Chicago helped convince Navy brass to begin the gradual process of desegregation.

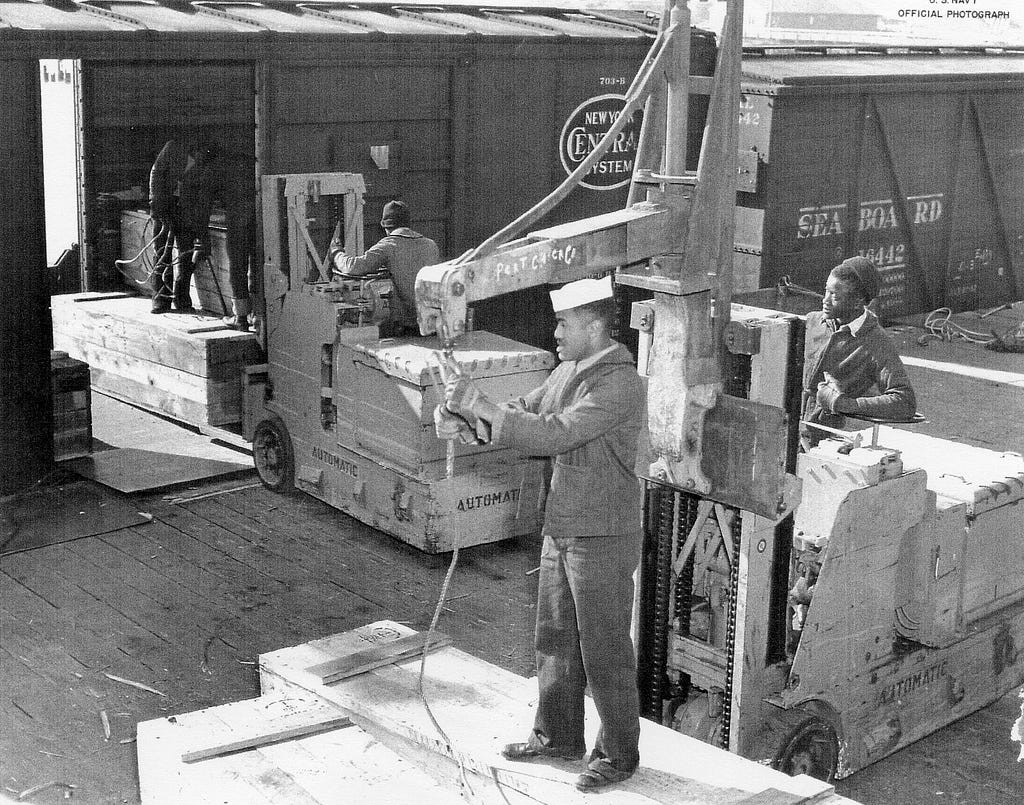

During World War II, the Navy loaded thousands of pounds of explosives onto cargo ships headed to the Pacific theater at Port Chicago, near the mouth of the Sacramento River. The ammunition, artillery shells, and torpedoes were stored in bunkers and transported to the docks by train, unloaded by hand, on carts or with winches, and carefully lowered into the holds of ships. The facility was built in 1942 in response to the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbor, and operated around the clock.

The work, like that of stevedores or longshoremen, was hard and dangerous and done in a hurry — with the added risk of handling live munitions. But the war in the Pacific depended on it.

Young black men enlisted to help the war effort and to escape Jim Crow. But the armed forces were just as segregated as American society writ large. Most black enlisted men were assigned to dead-end jobs loading, cooking, or driving on shore, instead of being shipped out to fight.

“What happened there was what was happening to black labor generally — namely, to be segregated into the most demeaning jobs, the hardest jobs, the lowest-paying jobs,” said UC Berkeley professor emeritus, Robert Allen, who wrote The Port Chicago Mutiny in 1989. “That was the history of black labor, going back to sharecropping, the Jim Crow system, all of that. These guys were products of that themselves.”

At Port Chicago, all of the 1,400 enlisted men assigned to load ammunition were black. Their commanding officers were white, and often urged them to work harder and faster, even placing bets on which crews could load the most tons of munitions per hour.

The sailors were told that the larger bombs didn’t have fuses and would be armed when they arrived at their destination. But this wasn’t always the case.

The enlisted men and their supervisors got minimal training on handling munitions and operating winches.

On the night of the accident, the E.A. Bryan cargo ship was about half full of explosives and fuel. The Quinault Victory was moored on the other side of the pier with boxcars full of bombs parked on the dock between the two ships.

Two explosions tore through the docks in quick succession, setting off a devastating fireball. The E. A. Bryan was destroyed, and 390 men were injured. The Quinault Victory was also blown to pieces and its stern landed in the water offshore. Seismographs at UC Berkeley registered the explosion as a small earthquake. Of the 320 men killed, only 50 could be identified. Many of the black survivors were tasked with clearing rubble and gathering the body parts of their fellow crewmen, while the white sailors got a month of leave to recover.

A month after the disaster, when the wreckage was cleared, the survivors were told to go back to work at the Mare Island Navy Yard in Vallejo.

“Keep in mind that half of them are teenagers,” Allen said. “These are kids, terrified of going back to work and getting killed in another explosion.”

More than 250 men refused to return to the docks. In peaceful times, it’d be called a strike. But in wartime, the Navy saw it as mutiny, and punishable by death. The men were thrown in the brig and locked up in a prison barge.

“I wasn’t trying to shirk work,” Seaman First Class Joseph Small explained later in an interview with Allen, the sociologist from Berkeley. “I don’t think these other men were trying to shirk work. But to go back to work under the same conditions, with no improvements, no changes, the same group of officers that we had, was just — we thought there was a better alternative.”

At the age of 23, Small was older than many of his crewmates, who looked up to him as a leader.

“I was a winch operator on the ship,” he recalled later. “And I missed killing a man on the average of once a day — killing or permanently injuring a man. And this was all because of rushing, speed. I didn’t want to go back into this. This was my reason for refusing to go back to work — to get the working conditions changed.”

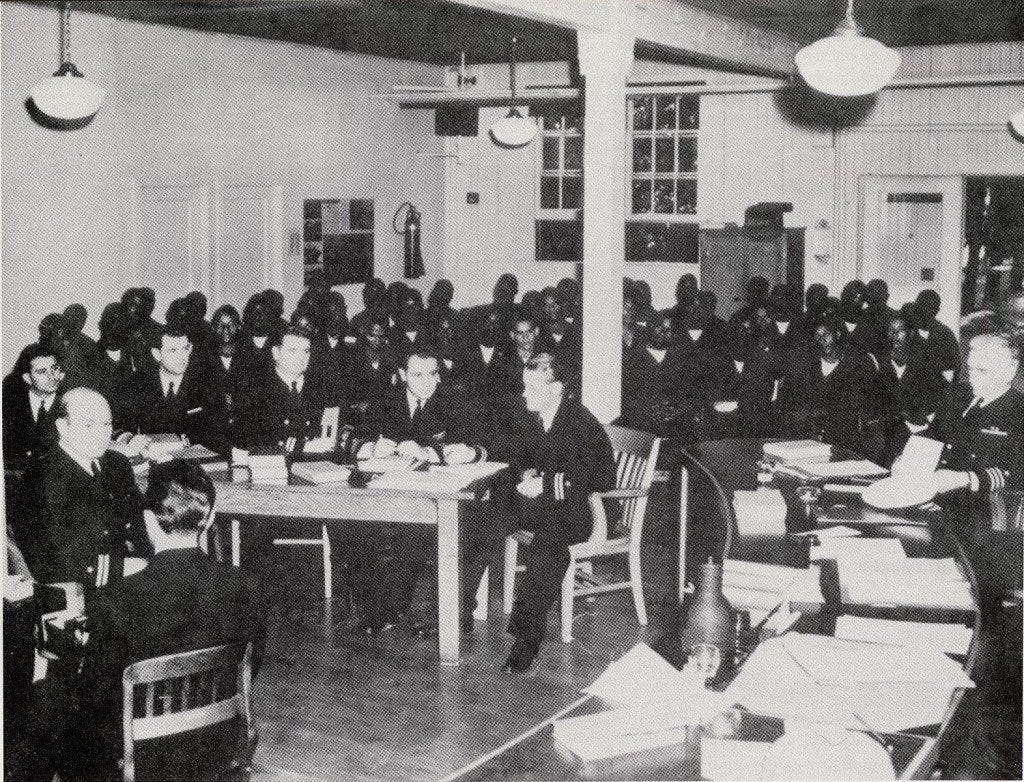

Under threat of death, 208 sailors went back to work. Naval prosecutors charged the remaining 50 with mutiny, arguing that they conspired to undermine the authority of the officers and disobeyed orders.

The case went before a military court-martial at Treasure Island. The defense argued that the young black sailors may have refused orders, but made no organized effort to seize command, and were therefore not guilty of mutiny. In fact, one jailed sailor had worked as a cook, not on the docks, and another had a broken wrist. So when asked if they would load munitions, they answered, “No.”

“I am willing to be governed by the laws of the Navy and do anything to help my country win this war,” testified Seaman Second Class Freddie Meeks. “I will go to the front if necessary, but I am afraid to load ammunition.”

Thurgood Marshall, then lead counsel for the NAACP, observed the court-martial and was dismayed by what he saw. The black sailors were blamed for causing the explosion and their capabilities were belittled on the stand. After a panel of admirals deliberated for less than an hour, they sentenced all 50 sailors to 8 to 15 years in prison and dishonorable discharges from the Navy.

At a press conference, Marshall said, “This is not 50 men on trial for mutiny. This is the Navy on trial for its whole vicious policy toward Negroes. Negroes in the Navy don’t mind loading ammunition. They just want to know why they are the only ones doing the loading!”

He wrote a pamphlet entitled, “Mutiny? The Real Story of How the Navy Branded 50 Fear-Shocked Sailors as Mutineers,” to publicize the plight of the Port Chicago sailors and the institutionalized racial discrimination in the U.S. military. He appealed on behalf of all 50 men the next year, but the court reaffirmed their convictions and lengthy sentences.

Meanwhile, First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt sent a copy of Marshall’s pamphlet to the Navy secretary, with a handwritten note expressing her wish that “in the case of these boys, special care will be taken.”

The Navy sent two divisions of white sailors to work at Port Chicago, the first step toward desegregation. Soon, black and white sailors were working, training, living and eating together on ships and bases around the world.

The case of the Port Chicago 50 helped pave the way for the Navy to desegregate well before President Harry Truman signed the executive order that formally integrated the rest of the military in 1948.

The convicted sailors were quietly released after a year and a half in federal prison. Most were shipped out to serve in the Pacific after the war ended.

The last survivor of Port Chicago blast, Freddie Meeks, was pardoned by President Bill Clinton in 1999, as part of a campaign to raise awareness about this chapter of World War II history. The rest of the Port Chicago 50 refused to ask for pardons because they believed only the guilty need to ask for forgiveness. They maintained all along that they’re not guilty of mutiny and pushed for exoneration instead. Meeks died in 2003.

In 1994, Congress asked the Pentagon to review the case. The Navy found that racism influenced assignments during World War II, but the convictions weren’t “tainted by racial prejudice.” Navy brass refused to expunge the convictions because sailors are required to obey orders, even if those orders are life-threatening.

Also in 1994, a group of private citizens called the Friends of Port Chicago placed a plaque at the waterfront site to remember the sailors, merchant marines and civilians who died there. They continue to push for a posthumous exoneration of all 50 sailors.

In 1999, President Barack Obama made the site of the explosion part of the National Park System. But since the location is surrounded by a working Navy base, visitors must book guided tours two weeks in advance.

This explosion killed hundreds of black sailors and eventually helped desegregate the U.S. military was originally published in Timeline on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Powered by WPeMatico