4 Things You Learn From Making 200 Calls A Night For Hillary

The Colorado Democratic ground game is drunk. It’s the eve of the first debate and our oracle has the E-Day odds at 50/50. A coin toss between Shiny Happy Neoliberal Yaaas Queenism and a postmodern performance artist lazily plagiarizing Margaret Atwood and Mike Judge. But data was supposed to save us. Good ole Mitt proved you can’t win an election with just white people, right? So why print this heresy, 538? Is Nate just trying to keep us on our toes, testing our faith, as oracles do?

Concerned citizens everywhere agree this pronouncement calls for cheap tequila, but we are pious Field Organizers, beholden to vows: No sleeping in the office. No personal calls in the office. Absolutely No Drinking In The Office, Under Any Circumstances, Even When A Volunteer Brings Prosecco. So we do these things in the parking lot, and we do them every day, so that by the time The Candidate trots onscreen in crimson, we have crumpled our doubts and need not interrogate them, training a muscle that none of us will admit, even afterhours, we are flexing more and more each week.

The leadership’s favorite adjective for us is “scrappy,” usually lobbed our way when we’re assigned tasks no vertebrate would accept — “thanks for being scrappy and driving 90 minutes south of your District to knock doors this weekend!” I write a simple Chrome extension that displays “scrappy” as “willing to work for less than minimum wage.” It catches on like wildfire.

We’re required to make 200 calls a night and knock about 100 doors a day. We’re in the office from 8AM to 10PM, on an easy day, and we make a flat $3,000 a month (supporter housing included, if you’re down to live in some affable stranger’s absent daughter’s bedroom). There are no weekends. We flutter our lids at each other as a joke about our sleeplessness, until we all develop persistent eye twitches as a symptom of insomnia. I constantly wonder how many other Field Organizers nationwide are regularly reminded they’ve been assigned to the most important congressional race in the country. The punchline is that, unlike virtually everybody, we staffers are disillusioned by everything except our candidate.

If you hung around a Democratic Field Office this autumn, the portrait of HRC as a corporate commandant whipping her reluctant base to the polls is alien to you. This profoundly exhausting gig is only even attemptable if you’ve taken a shot of the Kool-Aid. Some of us are in it for the down ballot elections. Some of us are With Her without reservation. I genuinely believe that the alternative is apocalyptic, which I’m reprimanded for saying on the phone and then encouraged to repeat once it becomes clear that it’s luring volunteers through our door.

I promised a listicle, so let me skip to the good stuff and tell you everything you learn from working the final months of a Presidential campaign:

1. When you have to make hundreds of calls a night, you will be instructed many, many times, to please enjoy the music while your party is reached. You won’t. Not once.

2. The best way to get to the top of a campaign call list is to hang up on the organizer mid-call. Our only inputs are “In Favor,” “Not In Favor,” and “Undecided.” I didn’t personally do this, but the only agency FOs have over egregiously rude callers is to gleefully mark them the latter, which bumps you to our Evangelist Missionary Five Calls A Day Until You’ve Admitted The Whitewater Scandal Was A Hoax Department. Just tell them you’ve moved. Or you’re dead.

3. Elections are won and lost based on who can manipulate the highest number of mercenary retirees into performing menial tasks for free.

4. Boredom can’t kill you, but you will wish it could.

It’s Item #3 I find most revelatory. It’s not hard to conjure the Venn Diagram if you think about it — you’ve got your People Who Give A Shit About The Election circle and your People With The Time And Financial Security To Harangue Strangers On Weekdays circle and then Retirees smack dab in the middle, just above we 20-somethings fleeing adulthood. And even through whatever defenses bulwark anyone whose gig depends on emotional labor, something about these people gets to me.

There’s Bob, a dapper Vietnam vet who clearly visits Mr. Rogers’ tailor, and chooses to knock more doors than we do on any given Sunday despite a bad back. There’s Georgette, who tears through call sheets insatiably, chemo be damned, like an English major pounding out papers on Adderall. There’s Arnold, a veritable data wizard and my Soul Twin as far as taste in TV, although he’s far better at recalling Klingon maxims than I am. And Mary, whose dialect I have not heard outside of film noir, who makes the grueling trek from her car to our phone bank every Tuesday and Thursday night, rain or shine. You can tell she hates asking you to hand her her cane.

These people will help us exceed insanely high call goals, but more importantly, we feel genuine affection for them. We shoot the shit about the Cubs, about impending dates and family drama, about Dr. Who and the latest speedbumps in the news cycle, which seem increasingly personal as the Day of Reckoning closes in. We talk about James Comey like a drunk uncle who just ran over the family dog. Our narrative on The Opponent changes from week to week; sometimes he’s a Drunken Toddler, other days a Sinister Oligarch, a boogeyman we can fear without taking too seriously.

Their earnestness makes me feel both hopeful about our chances and profoundly uncomfortable in a way I am only now able to articulate. It’s not that we’re lying to them — we believe everything we say. What bothers me is the stuff I don’t say, the needling questions:

What are the odds that, in a community this small, calling the same tiny list of desired acolytes over and over again at dinnertime, based on metrics handed down from Brooklyn, isn’t just silly — it actively turns our prospects against us?

Why are we taking on a huckster whose demonstrated superpower is turning everything into a perverse strongman competition by trying to “stay above him” and “keep it to the issues?” Has nobody asked Jeb Bush how that whole thing worked out?

Is it possible that we’re fielding an insanely qualified Presidential candidate, but we haven’t come up with a more compelling emotive pitch than Fuck This Guy?

(To be fair, we actually did ask that first one, just once, at an 8AM all-hands meeting our State Director rolled into at 9:30. She told us to try making more calls.)

But we don’t have better answers. Smarter people than me will perform autopsies later, but in the present tense, the gospel is all we have. Our volunteers are fiercely inspired, derive so much optimism from the youthful confidence we project. And if we give up on HQ’s omniscient Model For Success, what is any of this for? I mean, Jesus Christ, think about that for a minute — if we take these questions too seriously, we have to consider that the fate of the free world hinges on, what? Bad sabermetrics? A game we play because it makes us feel like Good People Who Did Something?

And this last question brings the feeling into focus, makes me realize my unnamable queasiness isn’t because we’re taking advantage of our unpaid telemarketers — it’s because I’ve been them. Full of unflinching faith in magnetic leaders, ready to fight for a plan riddled with flaws I was too close to see, believing I was approaching the finish line when I was running in place. This is when our evening phone banks, frenetic and brimming with other people’s grandparents, start to trigger scattered memories, images of another group with whom our volunteers share only the same level of conviction:

I remember the melee as the cops battered our tent city, and the unwashed, undaunted entrepreneur hawking seaweed through the chaos with no loss of enthusiasm. I remember the rumors that the pigs were rolling in at midnight, so Occupy Boston should celebrate, because it’s 12:30 and WE’RE! STILL! HERE! I remember being impressed that the boy in the chef’s jacket kept chanting even as they massaged his face into the dirt.

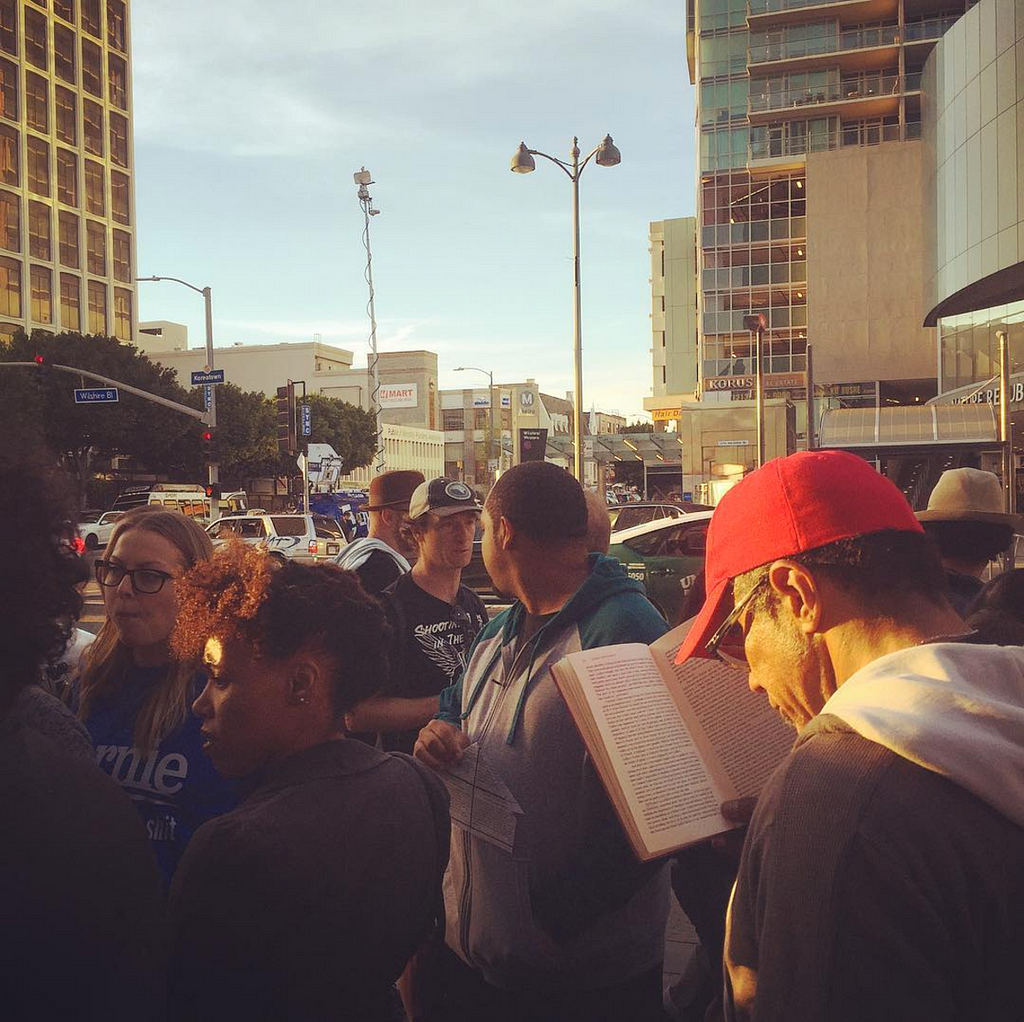

And then four years later, wading through crowds just as young but better-smelling, making small-talk beneath an Angelino sun on our pilgrimage to Feel The Bern. I was born too late for The Beatles and too early for the Thunderdome, so Senator Sanders would have to do. An interruption finally pierces the Matrix-level-déja-vù:

The two topless women in line had almost nothing in common with that Occupying culinary student, giggling and flailing their legs while half-smiling officers man-handled them into a patrol car. The last thing I saw before they slammed the door was the #FreeTheNipple sharpied just above the blonde girl’s piercing. I don’t know why I associate these moments. Perhaps because these protests of corporate governance and patriarchal body-policing ultimately made the same-sized dent in the power structures they opposed. Maybe you can see it if you squint.

I finally grew disillusioned with the Occupy movement not because of any police raid, but because it was ultimately Just For Us: The circular debates, the lack of leaders or unified policy goals — these things were conducive to our self-image as uncompromising radicals, not the implementation of change. Our leaderless system didn’t protect us from leaders, it just kept us at the mercy of whoever happened to be the most charismatic speaker in the camp. In retrospect, I think I underestimated the scale of that truism.

Speaking of non-sequiturs, let’s talk about fidget spinners, because I’m a Hip Teen™. A fidget spinner is a neat gizmo for hyperactive children, but you might not know that a precursor to the current product was devised on a trip to Israel as a way to “distract young [Palestinian] boys throwing rocks at [Israeli] police officers.” Regardless of how you feel about the plight of the Palestinian people, can we just relish in the callous absurdity of that image for a minute? The idea that a protestor’s rage could be redirected from driving off perceived invaders to an innocuous toy, implying our REAL problem is that the IDF is just too darn cheap to shell out for a few Beyblades in Gaza? What a feeble, apathetic narrative.

And it turns out narrative is everything. There isn’t one reason why Trump won, but he did a great job pandering to those who believe You Should Be Afraid Of Everyone — the Mexicans coming to take your job, the transgender predators stalking your bathrooms, the dastardly Muslims plotting your incineration. I am similarly wary of the increasingly popular Lefty plotline that Everyone Is Afraid Of Us — the Democratic establishment we will inevitably overthrow, the corporate media we will blind with our truths, the cowering Koch-bought patriarchs who know the Resistance is coming, all the way up to Cheeto Caligula himself. Never mind things like coalition-building, union outreach, local candidacies, class solidarity, or midterms — we’ll win because of course we will.

Which of these stories do you think drives more voters to the polls?

For our purposes, a fidget spinner is a political act that affords a level of self-gratification which obscures the tangible impact it will have on the world. This is bigger than “slacktivism,” and the people handing out fidget spinners don’t even have to have bad intentions — everyone involved can earnestly believe in the value of what they’re doing.

I promise I am not an Old Man Yelling At A Cloud, ranting that it’s always foolhardy to Believe In Stuff. I am saying that, if there’s one thing that wading waist-deep into both Granola Grassroots and Corporatized Leviathan politics has taught me, it’s that we should carefully interrogate anything that makes us feel brave. Because the sliminess of pandering has nothing to do with whether it works. Because, in the coming weeks, months, and years, you will be inundated on all sides by those who ask you to conflate serving their ends with heroism, and the sell won’t always be quite so obvious, or even intentional. Fidget spinners hide in plain sight.

Calling the same increasingly aggravated voters over and over again, because I guess it worked for a different candidate eight years ago, was a fidget spinner. Giving a studio money in the service of pissing off Nazis is a fidget spinner whether the movie’s any good or not. It’s handing a cop a Pepsi, but it’s also the gleeful circlejerk over our superiority to that image, because our activism could never be so performative, so oriented around patting ourselves on the back. So many leftbook arguments become as fidget spinnery as wearing a safety pin to show your support. I know people who don’t doubt for a second that voting for Hillary was a fidget spinner, voting for either of the two most popular parties was a fidget spinner, or that voting itself is, and will always be, a fidget spinner.

I’m not even certain who’s wrong. This is an account of one guy’s lived experience, not a treatise on Field Organizing as a whole. I’d like to end on a Grand Unified Theory for sniffing out fruitless activism, but nobody has that. And if you complain that I’m preaching with the benefit of hindsight, you’re right. And I know we have to train this muscle, the work of rational suspicion, of learning to discern between baubles on lures and the light at the end of the tunnel.

If we don’t, we risk conflating what feels right with what does good, our activism as revolutionary as a flag-colored profile picture, as scribbling a hashtag and running naked down the street.

Zach Ehrlich is the Creative Director of Defiant Network. He’s been a film and TV writer, a political operative, and most recently the assistant to an Oscar-winning director. Follow @EachZhrlich for further adventures.

4 Things You Learn From Making 200 Calls A Night For Hillary was originally published in Extra Newsfeed on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Powered by WPeMatico