A History of American Protest Music: How The Hutchinson Family Singers Achieved Pop Stardom with an Anti-Slavery Anthem

On March 18, 1845, the Hutchinson Family Singers were huddled in a Manhattan boarding house, afraid for their lives. As 19th Century rock stars, they didn’t fear the next night’s sellout crowd, but rather the threat of a mob. For the first time, the group had decided to include their most fierce anti-slavery song into a public program, and the response was swift. Local Democratic and Whig papers issued dire warnings and suggested possible violence. It was rumored that dozens of demonstrators had bought tickets and were coming armed with “brickbats and other missiles.”

“Even our most warm and enthusiastic friends among the abolitionists took alarm,” remembered Abby Hutchinson, and “begged that we might omit the song, as they did not wish to see us get killed.”

It wasn’t that most people didn’t know the Hutchinsons were abolitionists. The problem was that slavery (as well as its parent, racism) was an American tradition, and performers who wished to be popular did not bring their opposition onto the stage. Five of our first seven presidents, after all, were slaveholders.

The song that would be performed the next night, “Get Off the Track!,” was unambiguous about the direction our young country was headed. It grafted an original antislavery lyric onto the borrowed melody of a racist tune, and the result was not just a hit, but a newfound popularity for the abolitionist movement. It’s not too much to say that the Hutchinson Family Singers helped invent pop stardom and punk rock; they subverted tired old tradition, turning it into successful new expression.

The Hutchinson Family Singers formed in Milford, New Hampshire, in 1839, and helped shape American music as independent from European. “Family concerts,” according to one historical article, “contained little of the operatic, less of the classical, and none of the mystical.” It was, instead, the origins of pop music. Particularly with the Hutchinsons, there was comedy, melodrama, morality tales, and a genre-defining stagecraft of non-musical cues — some of which bordered on hysteria They sang of lost children in the Alps, ships on fire, train wrecks, and the “progress of insanity.” (“No, by heaven I am not mad!” they screamed during the chorus of “The Maniac,” tearing at invisible asylum chains.)

They were young and attractive. Jesse, the lyricist and sometimes manager, was thirty-two. He stayed mostly backstage while the quartet — Judson, the temperamental poet; John, the theatrical one; Asa, the big-boned bass singer; and Abby, the pure maiden of just sixteen, whose “sweet manners won all hearts” — performed. They came across as plain-spoken and honest, singing in pure tones and ringing harmonies, with wholesome lyrics they were careful to enunciate.

At the beginning, the Hutchinsons were like the other thirty or so family bands touring the country. They needed something to set them apart, and it started with a costume. The Druid Horn Players appeared robed as “ancient priests,” the Old Folks Concert Troupe donned pre-Revolutionary War garb, and the Kilmistes sent out an older player with a feather in his cap, who announced the coming performance by “making a donkey of himself.” Another popular group, the Rainer Family Singers, claimed to originate from the Tyrolean Alps, and dressed accordingly in lederhosen and feathered hats. John saw the group perform. Soon Abby sported her own Swiss bodice, and joined her brothers on stage in an updated incarnation called The Aeolian Vocalists.

They were also baldly ambitious. After a Thanksgiving Day concert at their hometown Baptist Meeting House in 1839, John had a vision of singing “to numerous audiences…and witnessed the gathering in of piles of money — gold, silver, and quantities of paper.”

It’s not too much to say that the Hutchinson Family Singers helped invent pop stardom and punk rock; they subverted tired old tradition, turning it into successful new expression.

By 1844, and renamed the Hutchinson Family Singers, they were a massive touring success, drawing crowds in their thousands in Manchester and Boston. The Swiss Alps angle had been abandoned, as had too the novelty numbers where two brothers played three instruments with their feet. The Hutchinsons had become natural-born Americans.

If you were going to sing American, then you needed to draw from emerging national themes. The Hutchinsons chose egalitarianism. They were plainspoken teetotalers — “cold-water singers,” against slavery and for women’s rights.

Like The Partridge Family, they also had their own theme song, “The Old Granite State,” about the group’s Yankee origins:

Liberty is our motto

And we’ll sing as freemen ought to

Till it rings o’er glen and grotto

From the old Granite State

‘Men should love each other

Nor let hatred smother

Every man’s a brother

And our country is the world!’

When they performed the song for the Anti-Slavery Society’s annual meeting in Boston in 1843, the Hutchinsons added a new verse:

Yes, we’re friends of Emancipation

And we’ll sing a proclamation

Till it echoes through the nation,

From the Old Granite State,

That the tribe of Jesse

Are the friends of Equal Rights

“Oh, it was glorious!” wrote one attendee. “Slavery would have died of that music and the response of the multitude.”

By the mid-1840s, there was another form of popular American music, one in direct competition with Hutchinson family values. Minstrelsy was on the rise. White men with “blacked-up” faces sang racist songs in an exaggerated dialect, creating characters like Jim Crow, Gumbo Chaff, and Zip Coon. Blacks were portrayed in many ways — as naive, fun-loving children or preposterous dandies — anything that would provide entertainment and accomplish the fundamental goal of portraying “authentic” African Americans as being unworthy of uplift. They were too simple-minded, or greedy, or wily, or violent, to be treated as equals.

Blackface performer Dan Emmett, with a group from New York called the Virginia Minstrels, sang one of the genre’s most popular songs. “I come to town de udder night,” it begins in its mush-mouth vernacular,

I hear de noise den saw de fight

De watchman was a runnin’ roun’

Crying Old Dan Tucker’s come to town!

So get out de way! Get out de way!

Get out de way, Old Dan Tucker

You’re too late to get your supper

Tucker was a hardened sinner,

He nebber said his grace at dinner

De ole sow squeal, de pigs did squall

He ‘hole hog wid de tail and all

Here was the drunken brawler, another blackface stereotype helping to condemn a race to servitude. “Old Dan Tucker” was an undeniably catchy melody and a high-stepping breakdown. It was everything reformist music wasn’t: danceable, rhythmic, virile, and thrillingly secular.

Emmett was popular in the South for his biggest hit, “Dixie.” He claimed to have written “Old Dan Tucker” as well, but its origins probably predate him. (He may not have actually written “Dixie” either. There was a different understanding of intellectual property rights at that time.)

Meantime, the abolitionists were seen as party-pooping sourpusses. “We were right, and all the world about us was wrong,” wrote anti-slavery poet John Greenleaf Whittier. “We could look for no response but the laughs of derision or the missiles of the mob.”

John intervened after Asa expressed an interest in seeing the Virginia Minstrels. “I persuaded him not to,” John wrote in his diary. “So we had a family meeting, sang ‘Old Hundred,’ and talked about heaven.”

In the same month, Jesse Hutchinson wrote a new song, “Get Off the Track!” Bold to the point of combativeness and insistently rhythmic, it was different from the group’s sober, middle-class material. “Ho, the car Emancipation,” Jesse wrote, picturing the progress of equality as a speeding train, “rides majestic through our nation.”

Bearing on its train the glory

LIBERTY! A nation’s glory

Roll it along! Roll it along!

Roll it along! Through the nation

Freedom’s car, Emancipation

The melody he used, or rather appropriated, was from “Old Dan Tucker.”

“Get Off the Track!” was an immediate hit, at least with the abolitionist crowd. At its debut in May 1844 for the Anti-Slavery Society Meeting, people danced in the aisles, including speaker William Lloyd Garrison. Soon there were Abolitionist Frolics and picnics. People protested with music and dance, making the process altogether more enjoyable.

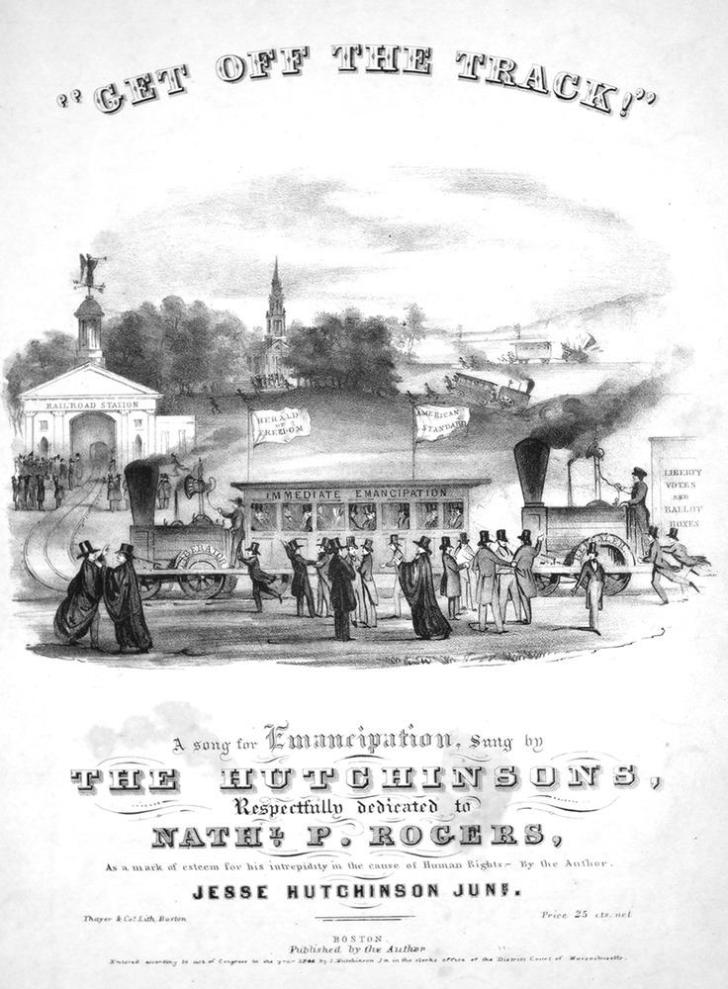

“Get Off the Track!” sheet music. Image via Johns Hopkins University Lester S. Levy Sheet Music Collection

A year later, as the frightened group sat in the Manhattan boarding house wondering whether to perform, they were approached by the landlady. “Boys,” she said, “if any disturbance occurs in the concert you look out for yourselves. I shall rush to the stage and take Abby bodily, and carry her off in my arms.” And so the decision was made that the show would go on.

The next night, backstage, Abby pointed to the program. “Gentlemen,” she told her brothers, “we are going to sing this tonight, if we have to die for it.”

They took the stage. Jesse ran out from the wings to join his brothers and sister. They began the song, Abby remembered, “with a fervor and enthusiasm greater than was our wont.”

By this time they had the performance down. To say the song was uptempo is understatement: it came at a gallop, the words falling like hammer blows. As each frantic verse progressed, the group abandoned musical phrasing and time. They waved their arms and shouted, “Get out of the way!”, as if people were about to be obliterated by the inevitable.

“And when they came to the chorus-cry that gives name to the song,” wrote N.P. Rogers, who witnessed the debut performance, “when they cried to the heedless proslavery multitude that were stupidly lingering on the track…standing like deaf men right in its whirlwind path, the way they cried ‘Get Off the Track,’ in defiance of all time and rule, was magnificent and sublime.”

The reaction was explosive. At first, John recalled, “the audience hissed; then some began to cheer, and there was a tug of war; finally the cheers prevailed.” After they finished, Abby wrote, “and when we sat down, the applause was tremendously overwhelming.”

The Hutchinson Family Singers went on to startling success. They toured Ireland, Scotland, and England with Frederick Douglass, and forced American theater owners to integrate their venues.

In November, 1855, three brothers of the family founded the town of Hutchinson in Minnesota. It forbade liquor, bowling alleys, and gambling of all types, and granted that women “shall enjoy equal rights with men and shall have the privilege of voting in all matters not restricted by law.”

During the Civil War, when General George McClellan kicked the group out of the Union lines for being too fiercely abolitionist, president Lincoln reinstated them, saying, “It is just the character of song that I desire the soldiers to hear.”

The Hutchinson Family Singers were, according to one critic, “exactly what Americans — the children of a young, bold republic — ought to be.”

Minstrelsy never quite went away. By the end of the century, it had transformed into another popular blackface genre, the Coon Song, in which blacks were portrayed as razor blade-wielding, watermelon-eating layabouts and thieves. African Americans weren’t allowed to make blues recordings until 1920, and movie star Al Jolson appeared in blackface in 1927’s massive hit The Jazz Singer.

“Old Dan Tucker” persisted too, moving away from its racist past to a new life as a hillbilly nonsense song:

Old Daniel Tucker wuz a mighty man

He washed his face in a fryin’ pan

Combed his head wid a wagon wheel

And he died wid de toofache in his heel

But before the Hutchinson family began their career, way away on a hill overlooking Lake Russell in Elbert County, Georgia, there stood a moldering headstone. Interred beneath it since 1818 was Daniel Tucker, a Methodist minister, Revolutionary War veteran, farmer, and ferryman. In life he was beloved of the local slave population, as he used much of his spare time to teach and pray with them. This is why it was said that he was usually home too late to get his supper.

There are those who say “Old Dan Tucker” was originally about this man. That’s the one part of this story that’s impossible to know.

***

Tom Maxwell is a writer and musician. He likes how one informs the other.

Editor: Mark Armstrong; Fact-checker: Matthew Giles