By the Reflection of What Is : Longreads

On the aesthetics, performance, and “majestic wrath” of Frederick Douglass, the most-photographed American of the nineteenth century.

John Stauffer and Zoe Trodd | Picturing Frederick Douglass: An Illustrated Biography of the Nineteenth Century’s Most Photographed American| Liveright | Nov. 2015 | 22 minutes (5,654 words)

The following excerpt appears courtesy of Liveright Publishing.

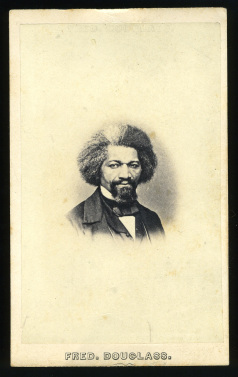

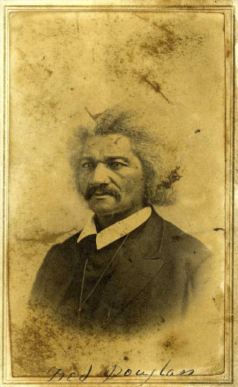

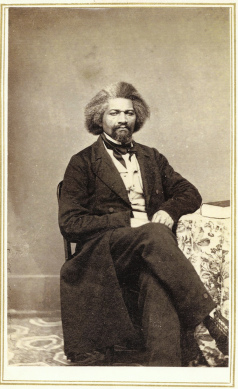

Frederick Douglass was in love with photography. During the four years of civil war, he wrote more extensively on photography than any other American, even while recognizing that his audiences were “riveted” to the war and wanted a speech only on “this mighty struggle.” He frequented photographers’ studios and sat for his portrait whenever he could. As a result of this passion, he also became the most photographed American of the nineteenth century.

It may seem strange, if not implausible, to assert that a black man and former slave wrote more extensively on photography, and sat for his portrait more frequently, than any of his American peers. But he did. We know this because Douglass penned four separate talks on photography (“Lecture on Pictures,” “Life Pictures,” “Age of Pictures,” and “Pictures and Progress”), whereas Oliver Wendell Holmes, the Boston physician and writer who is generally considered the most prolific Civil-War era photo critic, penned only three. We have also identified, after years of research, 160 separate photographs of Douglass, as defined by distinct poses rather than multiple copies of the same negative. By contrast, scholars have identified 155 separate photographs of George Custer, 128 of Red Cloud, 127 of Walt Whitman, and 126 of Abraham Lincoln. Ulysses S. Grant is a contender, but no one has published the corpus of Grant photographs; one eminent scholar (Harold Holzer) has estimated 150 separate photographs of Grant. Although there are some 850 total portraits of William “Buffalo Bill” Cody and his Wild West Show, and 650 of Mark Twain, no one has analyzed how many of these are distinct poses, or photographs as opposed to engravings, lithographs, and other non-photographic media. Moreover, Cody and Twain were a generation younger, and many if not most of their portraits were taken after 1900, when the Eastman Kodak snapshot had transformed the medium, bringing photography “within reach of every human being who desires to preserve a record of what he sees,” as Kodak declared. In the world, the only contemporaries who surpass Douglass are the British Royal Family: there are 676 separate photographs of Princess Alexandra, 655 of the Prince of Wales, 593 of Ellen Terry, 428 of Queen Victoria, and 366 of William Gladstone.

Douglass’s passion for photography, however, has been largely ignored. He is, perhaps, most popularly remembered as one of the foremost abolitionists, and the preeminent black leader, of the nineteenth century. History books have also celebrated his relationship with President Lincoln, the fact that he met with every subsequent president until his death in 1895, and that he was the first African American to receive a federal appointment requiring Senate approval. His three autobiographies (two of them bestsellers), which helped transform the genre, are still read today. Yet, because his photographic passion has been almost completely forgotten, historians have missed an important question: why would a man who devoted his life to ending slavery and racism and championing civil rights be so in love with photography?

The first part of the answer is that Douglass embraced photography as a great democratic art. More than once he praised Louis Daguerre, the founder of the first popular form of photography, the daguerreotype, and hailed him as “the great discoverer of modern times, to whom coming generations will award special homage. . . . What was once the special and exclusive luxury of the rich and great is now the privilege of all. The humblest servant girl may now possess a picture of herself such as the wealth of kings could not purchase fifty years ago.”

Poets, prophets, and reformers are all picture-makers.

It should be noted that Douglass and photography came of age together. Born in February 1818, he escaped from slavery on September 3, 1838, a year before Daguerre and Henry Fox Talbot created the first forms of photography. For the rest of his life, he would mark his new birth of freedom by celebrating it in place of his unknown birthday. He began his career as an abolitionist orator in 1841, just as technical improvements reduced exposure times, enabling the proliferation of daguerreotype portraits. Portraits fueled the demand for photography and constituted over 90% of all images in the medium’s first five decades.

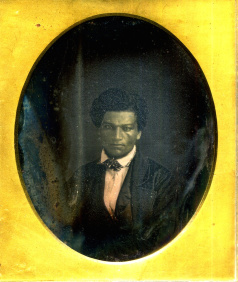

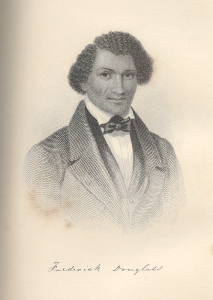

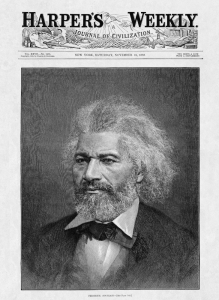

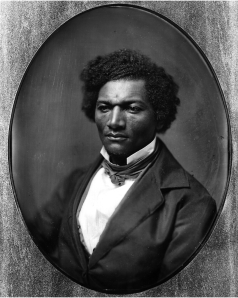

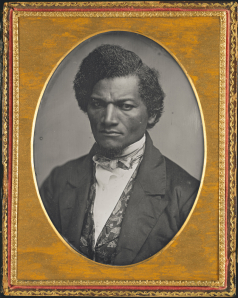

He first sat for a photograph, a daguerreotype, around 1841 [plate 1]. After publishing his best-selling autobiography in 1845, he lectured throughout the British Isles for two years. There he received his legal freedom and was introduced to The Illustrated London News, the world’s first (and hugely successful) pictorial weekly. The Illustrated disseminated photographs and sketches by cutting engravings from them, enabling readers to receive the news visually for the first time. In 1846, Douglass was twice featured in the paper, and when he returned to the United States in 1847 to launch a newspaper, it was increasingly common for books to be illustrated with frontispiece engravings cut from photographs. Four years later, the American illustrated press was launched in Boston with Gleason’s Pictorial Drawing-Room Companion, followed by the wildly popular Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper in 1855 and Harper’s Weekly in 1857. By then, there were photographic studios in every city, county, and territory in the free states, and new forms of photography to choose from, notably the tintype and ambrotype. Virtually every Northerner could afford to have his or her portrait taken.

From the 1850s on, the free states enjoyed a love affair with photography that surpassed every other nation on earth. The American South, however, lacked the cities, roads, entrepreneurship, and other aspects of a capitalist infrastructure that enabled photography to flourish in the North. Moreover, in their efforts to defend slavery, Southerners suppressed freedoms of speech, debate, and the press, including photography and visual images.

Early on, Douglass recognized this close connection between photography and freedom. He defined himself as a free man and citizen as much through his portraits as his words. The democratic art of photography echoed the freedom articulated in the nation’s founding document. His own freedom had coincided with the birth of photography, and he became one of its greatest boosters.

The second reason for Douglass’s love of photography is that he believed in its truth value, or objectivity. Much as his Bible referred to an unseen but living God, a photograph accurately captured a moment in time and space. Even more than truth-telling, the truthful image represented abolitionists’ greatest weapon, for it gave the lie to slavery as a benevolent institution and exposed it as a dehumanizing horror. Like slave narratives (Douglass was a master of the genre), photographic portraits bore witness to African Americans’ essential humanity, while also countering the racist caricatures that proliferated throughout the North.

Douglass paid close attention to such caricatures. He noted with scorn in 1872: “I was once advertised in a very respectable newspaper under a little figure, bent over and apparently in a hurry, with a pack on his shoulder, going North.” And he was all too familiar with the wider tendency toward racist depictions of African Americans: “We colored men so often see ourselves described and painted as monkeys, that we think it a great piece of good fortune to find an exception to this general rule,” he wrote in 1870.

Photographers, however, recognized that their medium lied—many self-consciously manipulated the image, solarizing it, airbrushing out unwanted subjects, or distorting it in other ways. But Douglass and most patrons of the art believed that the camera told the truth. Even in the hands of a racist white, it simultaneously created an authentic portrait and a work of art. Neither Douglass nor his peers recognized any contradiction between photography as an art, and as a technology.

Thirdly, Douglass believed that photography highlighted the essential humanity of its subjects. This was because of the medium’s ability to produce portraits for the millions. Influenced by Aristotle’s Poetics and the writings of Ralph Waldo Emerson and Thomas Carlyle, Douglass argued that humans’ proclivity for pictures is what distinguished them from animals: “Man is the only picture-making animal in the world. He alone of all the inhabitants of earth has the capacity and passion for pictures.” He summarized the significance of a photograph of Hiram Revels, the first African American senator, by saying: “Whatever may be the prejudices of those who may look upon it, they will be compelled to admit that the Mississippi Senator is a man.”

Emphasizing the humanity of all humans was central to Douglass’s reform vision, since most white Americans believed that blacks were innately inferior to whites, lacking in reason and rational thought. Furthering that view were Ethnologists (precursors of anthropologists), who argued that blacks had smaller craniums, and brains, than whites, and thus lacked whites’ cognitive abilities. In an 1854 speech, “Claims of the Negro Ethnologically Considered,” Douglass engaged ethnologists’ methods of comparing craniums and blacks’ and whites’ comparative capacities for reason, but with limited success. After his “awakening” to the philosophical power of photography, however, he dismissed ethnologists’ methods out of hand. “Dogs and elephants are said to possess reason,” he says. But they lacked “imagination,” the realm of thought enabling humans to create pictures of themselves and their world. Douglass exposed ethnologists’ faulty method of analysis: they “profess some difficulty in finding a fixed, unvarying, and definite line separating . . . the lowest variety of our species, always meaning the Negro—from the highest animal.” The line separating humans from other animals was quite clear, Douglass emphasized, as philosophers from Aristotle forward had acknowledged: “man is everywhere a picture-making animal and the only picture-making animal in the world. The rudest and remotest tribes of men manifest this great human power and thus vindicate the brotherhood of man.” The picture-making power was “a sublime, prophetic, and all-creative power.”

The fourth reason for Douglass’s love of photography is that it inspired people to eradicate the sins of their society. The power of the imagination allowed people to appreciate pictures as accurate representations of some greater reality. It helped them try to realize their sublime ideals in an imperfect world. As Douglass put it in an adage inspired by his reading of Thomas Carlyle: “Poets, prophets, and reformers are all picture-makers—and this ability is the secret of their power and of their achievements. They see what ought to be by the reflection of what is, and endeavor to remove the contradiction.” Douglass considered himself all three: a poet, prophet, and reformer. So did most other abolitionists. As a group, abolitionists and antislavery advocates, from Douglass and Lincoln to Whitman and Sojourner Truth, had their portraits taken with greater frequency, distributed them more effectively, and were more taken with photography, than other groups. Photography inspired them to remove the contradictions between what ought to be and what is.

Douglass recognized, however, that the power of photography depended upon its circulation in the public sphere. Photographs, like writing, needed to be published in books, newspapers, broadsides, and pamphlets in order to be disseminated. Whereas a daguerreotype or ambrotype offered a private viewing experience, its publication sent it into the world and made it public. Through the dissemination of his image and word, Douglass photographed and wrote himself into the public sphere, became the most famous black man in the western world, and thus acquired cultural and political power.

Negroes can never have impartial portraits at the hands of white artists

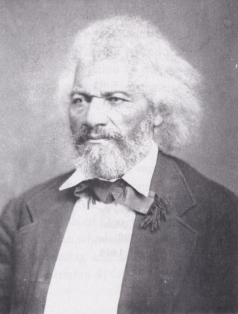

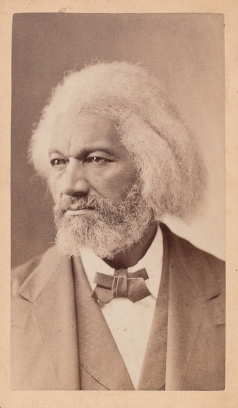

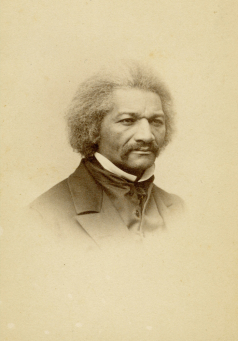

His portraits and words sent a message to the world that he had as much claim to citizenship, with the rights of equality before the law, as his white peers. He knew, as James Russell Lowell put it, that “(t)he very look and bearing of Douglass are eloquent, and are full of an irresistible logic against the oppression of his race.” His likeness embodied his cause of racial equality. This is why he always dressed up for his sittings with photographers, appearing “majestic in his wrath,” as one admirer said of his portrait, and why he labored to speak and write with such eloquence. He was widely considered one of, if not the, greatest orators in the Civil War era, more eloquent even than Lincoln or Emerson. It was through his images and words that he “out-citizened” white citizens, at a time when most whites did not believe that blacks should be citizens.

Douglass made every effort to circulate his photographs. He shared them with absent family members and close friends. He gave them as gifts to new friends, for example to Susan B. Anthony. He used them to garner subscriptions to his newspaper, thereby disseminating them further. And his photographs helped promote his talks. After the Civil War he became a speaker with the Redpath Lyceum Bureau, organized by the abolitionist James Redpath. The Bureau used a lantern slide of Douglass to advertise his affiliation to the agency.

But Douglass faced a problem in trying to disseminate his portrait on a mass scale. The half-tone process, which enabled photographs to be mass-produced, would not be perfected until the twentieth century. While he had to rely instead on engravings cut from photographs for book and newspaper illustrations, he did not have the same faith in the objectivity of an engraver (or painter) as he did of a camera. In 1849 he discovered an engraving of himself, cut from another engraving that possibly stemmed from a painting, in A Tribute for the Negro, by the British abolitionist Wilson Armistead [plate 2.6]. The engraver had portrayed Douglass with a slight smile. Douglass was outraged, and in his newspaper he noted that his portrait had “a much more kindly and amiable expression than is generally thought to characterize the face of a fugitive slave.” Although he was no longer a fugitive, he wanted the look of a defiant but respectable abolitionist. He then attacked the fallibility of engraving and painting: “Negroes can never have impartial portraits at the hands of white artists,” he stated. “It seems to us next to impossible for white men to take likenesses of black men, without most grossly exaggerating their distinctive features. And the reason is obvious. Artists, like all other white persons, have adopted a theory respecting the distinctive features of Negro physiognomy.” The vast majority of whites could not create “impartial” likenesses because of their preconceived notions of what African Americans looked like.

Douglass’s criticism of white artists highlights why he was so taken with photography. As an art and a technology, photography overcame whites’ “preconceived notions” of blacks; the camera, unlike an engraving or painting, represented them accurately. Douglass surmounted the problem of disseminating his photographs using an unreliable medium by hiring engravers he could trust. John C. Buttre was his preferred engraver.

Still, even a faithful engraving lacks the extraordinary detail of the photograph on which it was based. In fact engravings may appear to us today as crude representations. But they and lithographs were the only available processes for disseminating a photograph. Significantly, most Americans treated engravings cut from photographs as objective or “authentic,” much as most people today interpret a half-tone photograph in the New York Times as truthful. So did Douglass; if the engraving in Armistead’s book had in fact been drawn from a painting, then there are no known instances of Douglass critiquing an engraving cut from a photograph. The illustrated press, from Illustrated London News to Frank Leslie’s and Harper’s Weekly, referred to engravings cut from photographs in their pages as “photographs,” whereas engravings from sketches were called “sketches.” Editors simply ignored the transfer process necessary to mass-produce an image. While the truthfulness of sketches from “eyewitness” artists were sometimes challenged, virtually no one “questioned the veracity of a photograph,” or an engraving cut from it.

By resolving the problem of circulating his “impartial” likeness, Douglass authorized millions of portraits to be sent into the world.

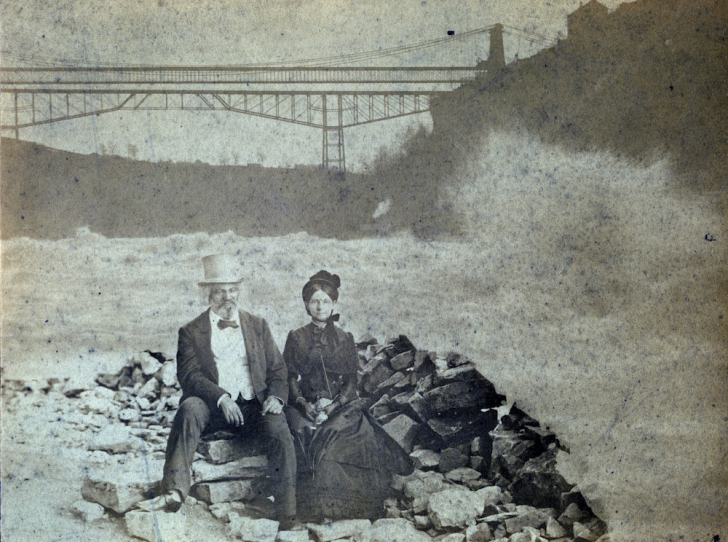

With very few exceptions, these were public portraits—designed to bolster his public persona. For Douglass, photography was not a personal or sentimental tool, a way to visualize family relationships or friendships. There are no extant images of Douglass with his first wife, Anna, or any of his children. The only photograph that falls into the category of private memento is a honeymoon shot from 1884 with his second wife Helen Pitts [cat. 110].

Cat. #110. Unknown photographer, August 1884. Niagara Falls, NY. Albumen print, National Park Service, Frederick Douglass National Historic Site

The sheer number of these public portraits, from his earliest known photograph as a young man with an Afro, circa 1841, to the postmortem portrait fifty-four years later, conveys not only Douglass’s faith in photography, but his understanding of the public identity he was crafting. By continually updating his public persona, he embraced what might be called a proto-modernist conception of the self that paralleled his radical egalitarianism. Just as he rejected fixed social stations and rigid hierarchies, so too did he repudiate the idea of a fixed self. He imagined the self as continually evolving, in a state of constant flux, which exploded the very foundations of both slavery and racism. Of course slavery and racism both depend upon some individuals being “fatally fixed for life.” Slavery creates a low ceiling above which no one can rise, and racism reflects the belief that some people are permanently superior to other people. Douglass’s fluid conception of the self conjoined art and politics. He went so far as to say that “the moral and social influence of pictures” was more important in shaping national culture than “the making of its laws.”

***

Douglass embraced almost all forms of photography, a truth that is evident from the archive of his portraits, which include virtually every format of nineteenth-century photography. There are nine daguerreotypes and four ambrotypes; one lantern slide and one salt print, which are comparatively rare; along with stereographs, cartes-de-visite, cabinet cards, wet-plate albumen prints, dry-plate prints, a glass negative and postcards. The only major forms not present in the archive are the British calotype — which was quite rare in America and circulated primarily among the British aristocracy — and the tintype, the cheapest and least vibrant form of nineteenth-century photography.

As Douglass posed for all these varied kinds of photographs, he sat frequently for fellow activists, such as Thomas Collins of Westfield, Massachusetts [plate 19]. He also rewarded loyalty. In 1859 the Philadelphia photographer John White Hurn helped Douglass escape after news broke of John Brown’s capture at Harpers Ferry. Douglass was in Philadelphia, and Hurn, a telegraph operator, suppressed the delivery of a message to the sheriff ordering Douglass’s arrest as a conspirator in Brown’s raid. He then warned Douglass, who left Philadelphia immediately and reached safety in Rochester, then Canada and England. When he returned to Philadelphia in 1862, he sat for Hurn, and did so again in 1866 and 1873 [plate 17]. Hurn produced a total of nine extant photographs, the most by any Douglass photographer.

Douglass was also inclusive in choosing photographers. They comprised women and men, whites and blacks, Southerners and Northerners. This diversity is partly owing to the fact that most of his portraits were taken while on the road, amid speaking tours. The sheer number of different photographers also reveals the comparative openness of the photographic profession. There were few barriers to entry for aspiring artist-entrepreneurs. Start-up costs were modest, and it took only a few months to learn the basic process.

At a time when “professional” implied men, Lydia Cadwell, an accomplished Chicago photographer, inventor, and gallery owner, created four stunning images of Douglass during his western tour in the winter of 1875-76 [plate 41]. Amid the guerrilla warfare of Reconstruction, Carl Giers, a German immigrant who settled in Nashville, photographed Douglass in 1873 during his trip to address the Tennessee Colored Agricultural Association [plate 38 and plate 38b]. Then too, many of the nation’s best-known photographers, from Mathew Brady [Plate 43] and Alexander Gardner to John Howe Kent and George Kendall Warren, also photographed Douglass. Gardner inadvertently includes Douglass (and John Wilkes Booth) in his famous photograph of the Second Inaugural; Douglass stands directly in front of Lincoln, and Booth in the balcony above him [figures 3 and 4].

Figure 3. Alexander Gardner, Lincoln’s Second Inaugural, 1865, detail (Frederick Douglass circled). Library of Congress

Figure 4. Alexander Gardner, Lincoln’s Second Inaugural, 1865, detail (John Wilkes Booth circled). Library of Congress

Four black photographers portrayed Douglass. Cornelius Battey, born in Augusta, Georgia in 1873, established a successful studio in New York with a white partner. Battey photographed Douglass in 1893, before becoming the instructor of photography at Tuskegee Institute in Alabama [plate 54]. James Reed formed another interracial partnership, teaming up with the white artist, Phineas Headley, in New Bedford, Massachusetts, where Douglass had lived for three years as a fugitive. In 1894, Reed created two of the most beautiful portraits of the elder Douglass [plate 59]. James Hiram Easton operated a studio in Rochester, Minnesota, from 1862 until the late 1880s, with his wife as his photographic partner. He photographed Douglass during a speaking tour through the Midwest in 1869. And James Presley Ball, one of the nation’s preeminent photographers, portrayed Douglass in two 1867 cartes-de-visite [plate 28].

Ball’s Cincinnati studio, in operation from 1851 to the 1870s, became known as the “Great Daguerreian Gallery of the West.” In 1854 Gleason’s Pictorial featured Ball’s gallery and declared that Ball photographed “with an accuracy and a softness of expression unsurpassed by any establishment in the Union” [figure 6]. “Scarcely a distinguished stranger” who came to Cincinnati did not “seek the pleasure of Mr. Ball’s artistic acquaintance,” Gleason’s noted.

Douglass was apparently so taken with Ball that he featured Gleason’s article, with an engraving of the gallery, on the front page of his newspaper, Frederick Douglass’ Paper. Ball’s gallery indicated that American visual art stemmed as much from blacks as whites. It offered up a microcosm of what America could be: an integrated place where patrons like Douglass could mingle, listen to music, and feel ennobled by the art as they waited for their portraits. True art could indeed break down racial barriers.

For Douglass, the diversity of photography reflected the diversity of humanity. “There have been many daguerreotypes taken of life,” he said in an 1860 speech on “Self-Made Men.” “They are as various as they are numerous. Each picture is coloured according to the lights and shades surrounding the artist” and sitter. The sailor, farmer, architect, and poet each viewed the world differently. Humanity was a “vast school,” and thus daunting to understand: “those who learn most seem to have most to learn.” Photography brought “focus” to the subject through its accurate portrayal of people.

Figure 6. S. C. Peirce, “Ball’s Great Daguerrian Gallery of the West,” c. 1854. Gleason’s Pictorial Drawing-Room Companion, 6:13 (April 1, 1854): 208.

It was as though Douglass viewed the world as a vast picture-gallery, which highlighted both the common humanity and sublime uniqueness of each person. In this, he seemed to echo Walt Whitman’s unpublished poem, “Pictures,” written in the 1850s:

In a little house I keep many pictures

hanging suspended — It is not a fixed house,

It is round — it is but a few inches from one side of it to the other side,

But behold! it has room enough — in it, hundreds and thousands, — all the varieties;

—Here! do you know this? This is cicerone himself;

And here, see you, my own States—and here the world itself,

bowling

through the air;

rollingThere is room enough in Whitman’s and Douglass’s “little house” for all the varieties of humanity. Like Cicerone, they are guides, showing visitors the fluid, all-embracing nature of photography and democracy. Douglass, even more than Whitman, was one of America’s great evangelists of the eye, introducing his viewers, readers, and listeners to a vision of interracial democracy, in which everyone was a citizen with equal rights before the law. His picture-gallery was all-inclusive.

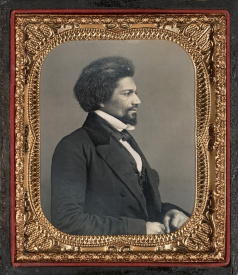

Douglass recognized too, that his relationship with the camera and photographer contributed to the transformative power of the medium. His portraits suggest that he understood his role as an artist or performer, part of a pas de trois with the photographer and camera. With that role, he acknowledged the challenges of sitting for a portrait: the “photographic process” was one of “stern serenity,” which tended to produce “something statue-like” in subjects, he said. The process required the sitter to be absolutely still for several seconds (much longer in the 1840s). Such a process might “deter some of us” from having their photograph taken, he added. And so he confronted the challenge much as a dancer did: by performing for the photographer, and appreciating the crucial role of timing, lighting, and set design.

Eventually, Douglass developed his own aesthetic. In his oeuvre, the vast majority of his portraits are closely cropped or vignetted. The effect draws attention to Douglass himself. There are comparatively few props to distract the viewer. He rejected the usual nineteenth-century studio practice of using elaborate backdrops, painted scenes of ornate columns and landscapes. Such objects detracted from his solemn, dignified performance of black masculinity and citizenship. On the rare occasion that he used a prop, he made sure it was significant: Lincoln’s cane; a book or newspaper [plate 18]; and a lion’s head chair, an acknowledgment of his own leonine mythology as “The Lion of Anacostia” at the “sunset” of his life [plate 57]. In other sittings, he was clearly experimenting with different angles, adjusting his clothing, and even trying out varied gestures.

In addition, as is now clear from the clusters of images taken at a single sitting, he worked with the photographer to obtain the “perfect” shot. For example, there are three similar photographs from a sitting with John Howe Kent in early 1874. In one, Douglass’s overcoat is undone, hanging loosely. In another, the overcoat is fastened but creased. In a third, he has straightened out his coat. It is the one with the straightened coat that exists in multiple archives, suggesting it is the one that Douglass authorized for sale and circulation.

This experimentation and artistry is reflected in the compelling force of his portraits. Understandably, photographers sought him out and apparently loved working with him. One friend owned “more than twenty pictures of him,” and in 1870 noted that “the photographers are running after him to sit for them.” Even now, save for a few isolated shots, his portraits consistently command our attention.

Douglass’s photographic self, much like his persona as an orator and writer, continually evolved. The earliest three photographs suggest that he was exploring this new medium, searching for an appropriate pose or “visual voice.” In the first known image, a daguerreotype from around 1841, he appears dazed or “statue-like,” as he would have said [plate 1]. No doubt this was partly because exposure times in 1841 lasted several minutes, as opposed to several seconds a few years later. In an 1843 daguerreotype the camera is positioned at the level of his chest, and he looks above it and to one side [plate 2]. This was the pose recommended by photographic manuals. “The eyes should be fixed on some object a little above the camera, and to one side, but never into, or on the instrument,” instructed the photography teacher Henry Snelling. The look evoked a statesman or visionary, as Alan Trachtenberg has noted. But Douglass was still a fugitive and not yet comfortable with his visual persona. In the daguerreotype his eyes seem only half open and partially shrouded in shadow (especially his right eye), thus complicating a visionary gaze. In an 1848 daguerreotype by the Edward White gallery, he looks askance with his head down, as if unwilling to trust the camera or the photographer [plate 3].

These three images indicate uncertainty about his early 1840s visual persona. Such uncertainty is reflected in an 1846 letter to a fellow fugitive: “I got real low spirits a few days ago, quite down at the mouth. . . . I looked so ugly that I hated to see myself in the glass.” What he sought was a look that could lay claim, for himself and other blacks, to respect and dignity, in essence the right of citizenship—-a visual voice of radical democracy.

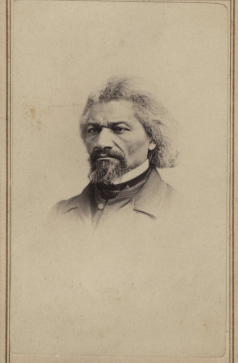

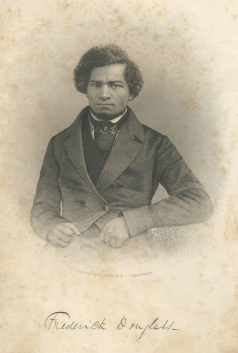

Douglass seems to have found that look in 1847, revealed in an 1850 daguerreotype that is a copy of one (now lost) from 1847. He stares sternly into the camera lens in a dramatic and crafted pose. It sent a message of artful defiance or majestic wrath, and with minor variations, it became his visual voice from the late 1840s through the Civil War. The frontispiece of his best-selling, second autobiography, My Bondage and My Freedom (1855), resembles the 1850 daguerreotype and similarly evokes artful defiance [plate 9]. Based on another lost photograph, it too draws attention to his physical strength and aggression, depicting as it does a broad-shouldered young man in a pugilistic pose, with furrowed brows and firm lips. Owing to the popularity of My Bondage, the frontispiece was probably the most widely disseminated portrait of Douglass in America until after the Civil War.

In the 1850s Douglass began fashioning for himself another, even more dramatic pose: the profile portrait. It was limited chiefly to distinguished men and women, and it generally evokes majesty rather than defiance. In the antebellum era there are only five known profile portraits of Douglass. In one, from around 1855, his fists are clenched, suggesting a look of majestic defiance [plate 10]. In the 1870s, after he became a distinguished statesman, the profile portrait became one of his favorites.

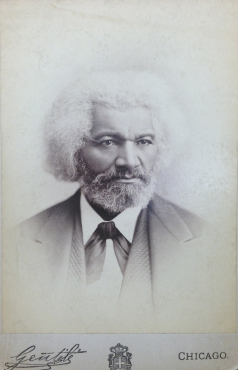

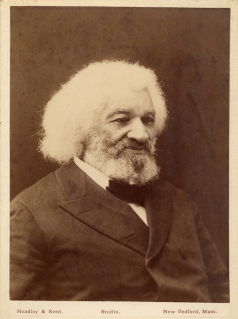

Over the 160 distinct poses, Douglass continually tried to articulate a vision of radical democracy. Three central themes stand out. Firstly, he almost never showed a smile, with the notable exception of an 1894 cabinet card six months before he died [plate 59]. Almost to the end of his life, he refuted the racist caricatures of blacks as happy slaves and servants. Secondly, he presented himself, in dress, pose, and expression, as a dignified and respectable citizen. Thirdly, his visual persona continually evolved, which undermined the foundations of slavery and racism. The photographs are thus a kind of visual autobiography. If Douglass wrote himself into public existence with his narratives, he also photographed himself into public existence, evolving across the years as a freedom fighter, steely visionary, wise prophet and elder statesman.

Perhaps the most noticeable visual marker of Douglass’s continual evolution is his facial hair. While nineteenth-century men experimented with hirsute faces, few did so as frequently as Douglass. He tracked, and often led, the prevailing fashion. In the 1840s, “a clean-shaven look was most prevalent,” writes Joan Severa. Douglass too, was clean-shaven. He grew chin whiskers in the early 1850s [plate 7] that evolved into a cropped fringe of muttonchop whiskers along the chin and jawline, also a trend at the time [plate 9]. By the mid-1850s he became a trend-setter with a full beard coupled with side-hair that covered his ears, a look that was not popular until late in the decade. He then began sporting a goatee, which he kept until about 1863. In January 1864 he anticipated another trend with a sporty walrus mustache, which would not become common for another two decades [plate 21]. Around 1865 he coupled his walrus mustache with a short ponytail. He kept his mustache until about 1873, at which point he briefly grew a full beard [plate 38]. Within a year, however, he shaved his chin whiskers, while retaining bushy sideburns that looped up to connect to his mustache. In 1875 he maintained a neatly groomed full beard, anticipating a look “affected by authority figures in the 1880s,” according to Severa. His beard and hair gradually lengthened and whitened until his death in 1895 [plate 160].

The evolution of his appearance, like his portraits, indicated his status as a “self-made man.” The appellation encapsulated his rise up from slavery; his abolitionism; his love of photography; and his faith that true art could break down racial barriers. “Self-made men” became for Douglass one of his signature speeches and a keyword denoting not riches but radicals who sought to eradicate the sins of their society as they evolved. The black abolitionist and physician James McCune Smith called Douglass an emblematic self-made man because he had “passed through every gradation of rank comprised in our national make-up and bears upon his person and his soul everything that is American.” Lincoln said something similar; after his first meeting with Douglass at the White House, he called him “one of the most meritorious men, if not the most meritorious man, in the United States.”

Douglass’s portrait gallery contributed to this persona as one of the nation’s preeminent self-made men. In certain respects it resembled the nation: both had come out from slavery and revolution to become a respected statesman or state. Then too, Douglass and his nation were both aspirational; they saw what “ought to be by the reflection of what is.” But unlike Douglass, most American statesmen did not seek to remove the contradiction between what was and what ought to be. While Douglass’s portrait gallery was all-embracing, America’s was narrow and petty. It continued to define itself as white.

As a result, Douglass’s portraits have served as an important visual legacy in the twentieth century and beyond, inspiring art that could break down racial barriers. His portraits connected past to present, summoning artists to create murals, sculptures, paintings, prints, drawings, and magazine covers based on the photographs. Douglass’s visual legacy protested lynching and segregation. It lobbied for civil rights and celebrated Black Power. It dignified the black body that white Americans, according to Ta-Nehisi Coates, have so often tried to destroy.

Plate 60 (cat. #160). Unknown photographer, February 21, 1895. Cedar Hill, 1411 W Street SE, Washington, DC. Cabinet card, National Park Service, Frederick Douglass National Historic Site

In Douglass’s awareness of the possibilities of imagery to shape public opinion, in the attempt by America’s first black celebrity to control and circulate his own image, was one of the first great battles in American history—a battle between racist stereotypes and dignified self-possession. Across fifty years of photographs, Douglass fought for the public image of African Americans. Across the next 120 years, in his visual afterlife, the photographs have fought on.

Source: By the Reflection of What Is : Longreads