In 1967, the hunt for a black serial killer in Cincinnati stoked racial unrest and led to a riot

Police deputizing 5,000—mostly white—citizens made it much worse

It began in October of 1965, with the gruesome sexual assault of Elizabeth Kreko. Kreko was approached by a man outside of her apartment in the peaceful Walnut Hills section of the city at around noon. He asked if he could speak with the caretaker and when she led him to the basement, he dragged her into a side room, raped her, and attempted to choke her to death with a double-knotted clothesline. She was found barely alive. Within two weeks, two more women in the neighborhood were attacked in similar fashion.

All three reported that their assailant had been a black male, but otherwise the descriptions differed. Less than a week later another woman, 39-year old Margaret Helton, was attacked by a black man who asked politely for directions, then dragged her into a car, told her she was being robbed, and wrapped a rope around her neck. She was able to scream, leaning on her horn as he ran off into the afternoon.

The attacks continued through the latter part of 1965 and into 1966, as fear gripped Cincinnati’s white community. In December, Emogene Harrington, 56, was found strangled with her clothing ripped in her apartment building by a double-knotted plastic cord. In January of 1966, an intruder attempted to choke a woman in her Walnut Hills basement. Her husband reported hearing the screams and chasing off a tall black man wearing a trench coat and hat. In April of 1966, Lois Dant was strangled and sexually assaulted in her Price Hill apartment by an assailant who reportedly knocked on her door asking for the apartment manager.

As the stories piled up, the investigation proved increasingly frustrating to police. Authorities wavered on whether or not these attacks were committed by the same person, but key elements seemed to link them. Ropes or cords were used to strangle the women in most cases, and most of the attacks included sexual assault But most importantly, the survivors reported that the assailant was black.

Police chief Jacob Schott announced that the same man had been responsible for the murders. “There cannot be three of them,” he told the press. Desperate to put an end to the threat, police expanded their squad, putting 22 men to work on over 1,000 tips. A Cincinnati Enquirer article dated June 25, 1966 ran the headline “Negro Killed Three Women, Police Say.”

An event of this magnitude shook the sleepy city to its core. Mark Twain once said, “When the end of the world comes, I want to be in Cincinnati. It is always ten years behind the times.” The town prided itself on its bucolic and virtuous disposition, largely removed from the terrors of nearby urban centers like Chicago and St. Louis. But in America, the discomfort of race way has a way of insisting itself upon everyone’s pretensions of innocence. After riots shook Watts in 1965 and nearly a decade of race-related turmoil had rocked the South, including Cincinnati’s southern neighbor, Kentucky, an October 1965 Gallup Poll cited civil rights problems as the number one worry in the country. Cincinnati was not immune. The sudden appearance of a cold-hearted and seemingly unstoppable rapist/murderer, combined with white America’s growing anxiety, made for a heady mixture.

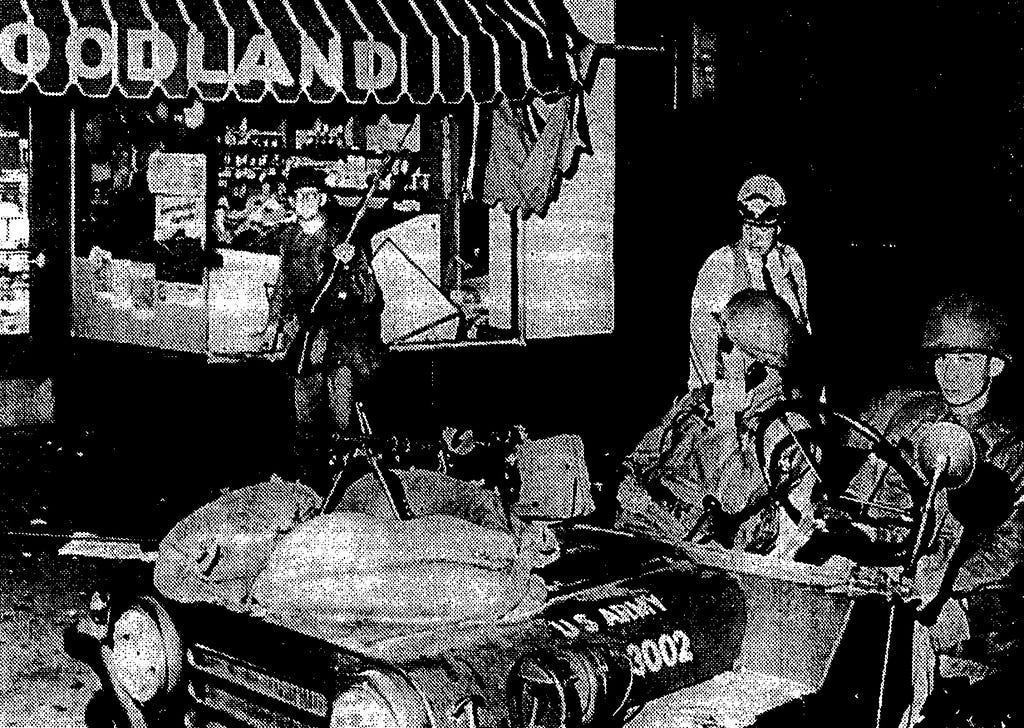

As the summer progressed, riots took place in Atlanta, Chicago, and Dayton, Ohio, just 53 miles northeast of Cincinnati. While the local assaults continued, police began to indiscriminately round up black men, particularly in Cincinnati’s Avondale neighborhood, and put them in lineups. Civil rights groups protested, but the environment of fear won out. Police would ultimately deputize a vast network of firefighters, meter readers, security guards, and mail carriers, to report any suspicious activity. At full strength, 5,000 citizens and police were working on the case. A hotline received 800 tips per day; 15,000 cars were checked out; and editorials were printed in the Enquirer begging the killer to come forward. Halloween would officially be moved to daytime.

Another grisly murder in August 1966 further changed the direction of the investigation. At around 2am, a cab driver, a short black man with a goatee, picked up 31-year-old Barbara Bowman from a cafe in the Rich Hill neighborhood. Later that evening, police would find Bowman lying dead on a sidewalk. She had been stabbed in the neck by a paring knife that lay several feet from her, along with a rope that was used to choke her. Her shoes and jewelry were found near the scene, her purse a little ways back. The cab was up on a curb and it was clear that she had tried to escape when the driver ran her down before stabbing and strangling her. The murder had not only been gruesome, it had also been uncharacteristically sloppy. Furthermore, Bowman, at 31 years old, was decades younger than all the other victims.

Also unlike the other cases, this one had witnesses galore: everyone who had been in the cafe, for starters. Another cab driver reported picking up an out-of-breath black man just blocks from the scene moments after the murder was thought to have taken place. Furthermore, the fake cab driver had picked up eight previous fares and interacted with dispatch throughout the night. Police were quickly able to assemble a composite sketch.

The murder of Alice Hochhauser two months later set events on an even faster downward spiral. Hochhauser, 51, was a mother and the wife of the chief surgeon at Good Samaritan hospital. She was brutally attacked, raped, and killed, in the garage of her home in the posh historic Gaslight district on October 11, 1966. The brutality of her murder, combined with the fact that it took place in a quiet, segregated, suburban neighborhood of tree-lined streets and luxury homes sent the city into full frenzy.

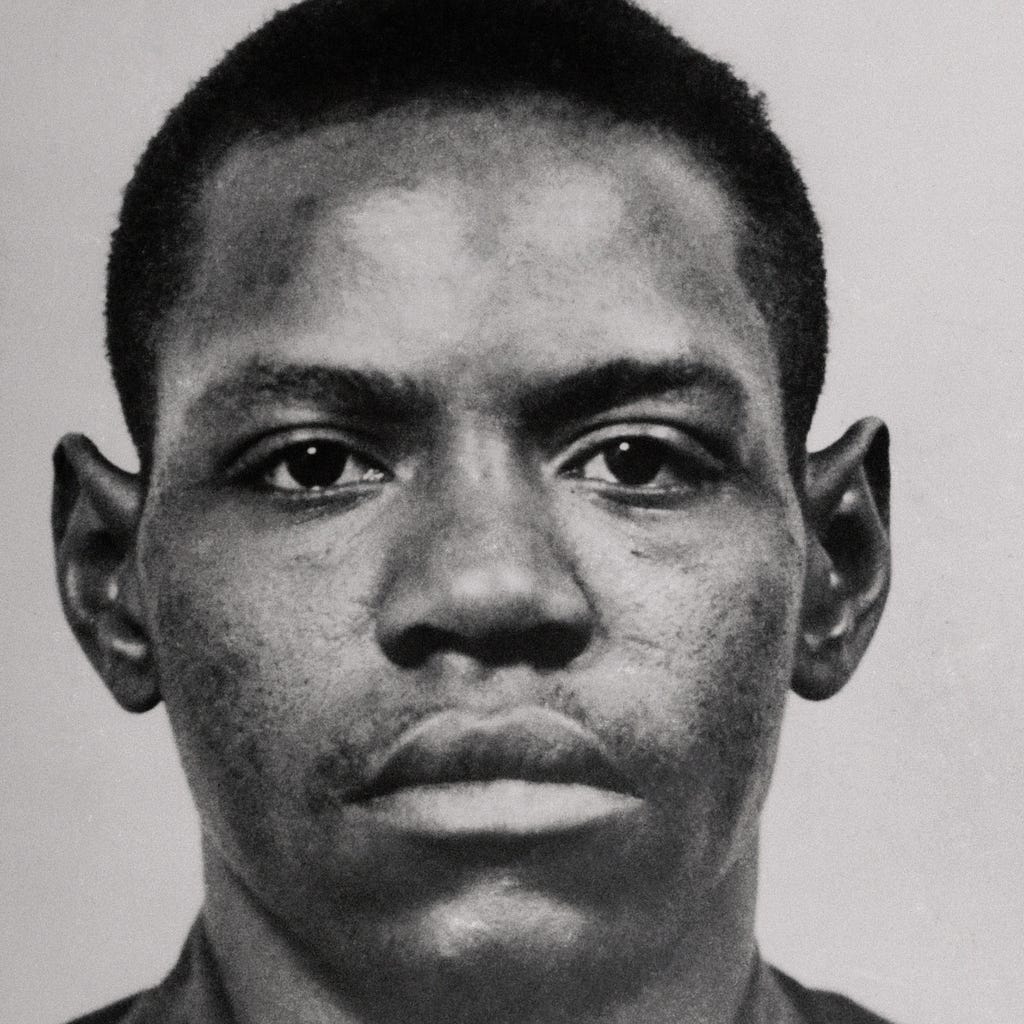

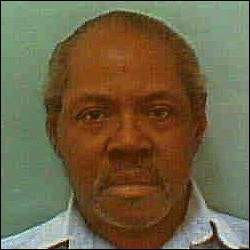

Another botched attempt to snare a victim resulted in police getting a license plate number which eventually led them to Posteal Laskey, a 29-year-old former cab driver who had a sex offense on his rap sheet. He was immediately identified by eight witnesses, though some were tentative. On December 15, 1966, Laskey was indicted for only one murder, that of 31-year-old Barbara Bowman.

The trial began on March 27, 1967. An all-white jury was seated. The judge selected had previously faced Laskey in 1958 and had said, in the court record, “Men like you should be put out of society for life.” Laskey’s attorneys petitioned for a venue change but were denied. As physical evidence was scant, the trial depended almost entirely on eyewitness testimony. Witness descriptions differed, but the prosecution was able to call forth a good number of people who could testify that Laskey had been seen, had used the cab in question, and had called into dispatch on the evening of Bowman’s murder. In Laskey’s defense were just five witnesses, two of whom were his mother and brother. Less than three weeks later, Laskey was found guilty of the Bowman murder and sentenced to death. While he was never charged with any of the other murders, police, investigators, and the press certainly gave the impression that Posteal Laskey was in fact the Cincinnati Strangler.

Laskey’s conviction, the racially charged investigation, and years of deep-seated institutional racism in Cincinnati meant that the city set was to explode.

In 1967, nearly 30 percent of Cincinnati’s population was black, but there was only one black seat on the city council. Nearly 40 percent of public schoolchildren were black, yet only one black person served on the school board. Organized protest had been plentiful in the city, but the outcomes had not changed. The NAACP organized a protest to draw attention to the lack of black representation in trade unions, to no avail. In 1963, Fred Shuttlesworth, who had been instrumental in the civil rights movement in Birmingham, organized an action against discriminatory practices at the county hospital, but the activists were arrested and charged with trespassing. In a trend that was echoed throughout the Long Hot Summer, young people in northern cities were growing increasingly disillusioned with the limitations of nonviolent protest. When it was laws that were oppressive, protests could be effective in changing them. But when it was attitudes, double standards, and a broadly racist culture that hounded black residents, marches and sit-ins did little.

Tensions in Cincinnati following the conviction of Laskey grew so thick that Martin Luther King made a special trip to the city to appeal for calm. That same day, however, Posteal Laskey’s cousin Peter Frakes picketed with a sign that said, “Laskey innocent, Cincinnati guilty.” Police arrested Frakes and charged him with trespassing and blocking traffic. This struck black residents as a particularly hollow use of the statute (when had white people been arrested for blocking traffic on the sidewalk?) and frustration mounted.

A tense protest meeting was held on June 12 and after it dissipated, a rock was thrown through a church window. Soon a fire was set in the street and a Molotov cocktail was hurled into a drug store where earlier in the day a group of black youths had argued with a white owner. That night there were 14 arrests made. The next night, unrest continued with fires, broken windows, overturned cars and more arrests. Violence became worse in the ensuing days. A black man was shot in the neck on his front porch. A 15-year-old white resident was critically wounded by crossfire in front of a gas station.

By the next day, 900 National Guardsman had been deployed to Cincinnati with “shoot to kill” orders. It took another 24 hours for the uprising to be entirely quelled and when it was 63 were injured, 404 arrested and one had died.

Laskey’s execution was never carried out. In 1972, the Supreme Court struck down all existing death sentences in Furman v. Georgia. So, Laskey lived in prison until he died in 2007. No one claimed his body and he was buried on prison grounds. Despite the fact that he was never tried for any other murder, at the time of his death the Enquirer still referred to him as the Cincinnati Strangler.

In 1967, the hunt for a black serial killer in Cincinnati stoked racial unrest and led to a riot was originally published in Timeline on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Powered by WPeMatico