Licensed to Ill: The Beastie Boys’ Complicated Legacy

Sexism and homophobia are forever tied to the Beasties’ debut—30 years on, so is their maturity and repentance

Last month marked the 30th anniversary of the Beastie Boys’ debut record, Licensed to Ill, one of the most famous and influential albums in hip-hop history. As the anniversary approached, I started to think about not only what the album meant to me in shaping my own musical taste, but also the way it impacted the culture at large. This is the album that brought hip-hop to the white kids in the suburbs — myself included — showing that rap music had much greater commercial appeal than many skeptics could imagine.

When we look back, we find a complicated legacy that led the Beastie Boys to both embrace and shun all that their debut LP stood for. Here are five observations about Licensed to Ill that stand out 30 years after its release.

1. The album is actually even more popular than you realize.

This seems obvious, but it’s important to not underestimate that this is still one of the best selling rap albums of all time, even 30 years later. Considering that so many naysayers in 1986 dismissed hip-hop as a novelty genre, this is incredible.

Hip-hop had been constantly increasing in popularity since its humble beginnings in the mid-70s, but it was Licensed to Ill that really shook up the culture and catapulted rap music to new levels of acceptance. It’s easy to group the Beastie Boys in with the rest of the closely-knit, Def Jam and Rush-affiliated artists like LL Cool J and Run-DMC. But at the time, Licensed to Ill stood out completely from the rest of rap music as a cultural phenomenon in itself. Of course, we must not ignore the obvious racial implications here — after years of critics dismissing hip-hop as being “too black” for mainstream America, it was three obnoxious Jewish boys who helped bring hip-hop to the masses.

The industry waited for years for another hip-hop album to do as well as Licensed to Ill, but no other album came close. In fact, it remained the best selling rap album until MC Hammer’s breakthrough in 1990. And if we’re only counting critically respected hip-hop artists — sorry, Hammer — it wasn’t until 1992’s The Chronic that a rap album made the kind of legitimate mark that Licensed to Ill made. For all the well-deserved love and adoration that the Golden Era gets, it’s important that we don’t forget that for hip-hop’s first 20 years, Licensed to Ill and The Chronic stand out as the two records that made the biggest impact in hip-hop becoming a mainstream cultural force.

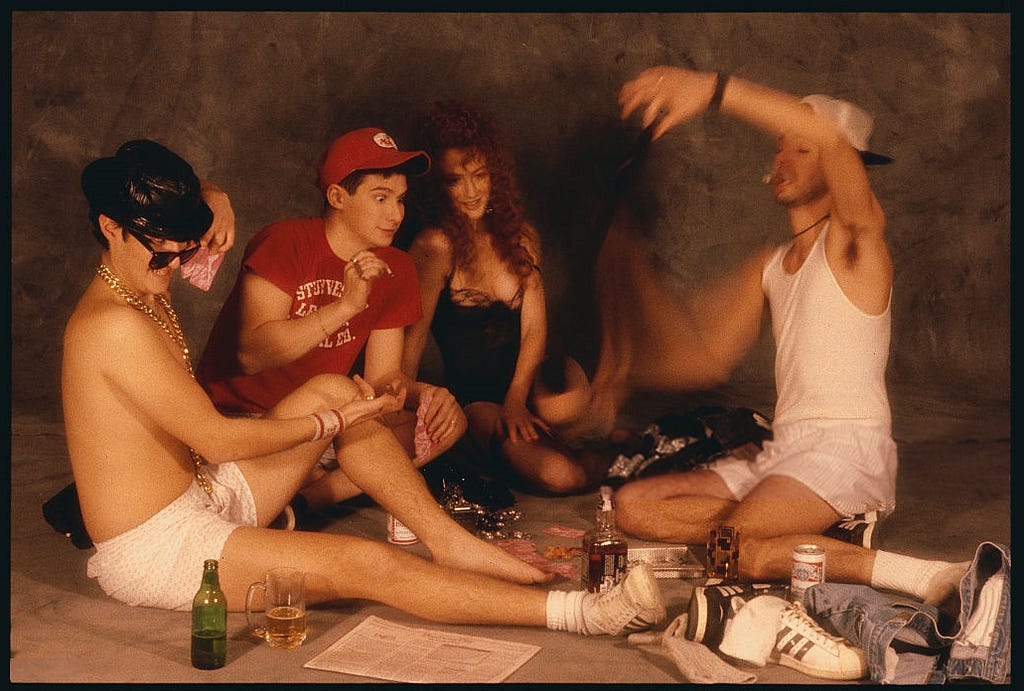

2. Sexism and homophobia are forever tied to ‘Licensed to Ill,’ but so is the Beastie Boys’ later maturity and repentance.

I was 7 years old when I bought Licensed to Ill and — like everyone else who got into music in the 80s and 90s — I was immediately obsessed with it. That obsession wasn’t just because “Fight For Your Right” and “No Sleep Til’ Brooklyn” were really catchy. The Beastie Boys themselves were extremely charismatic and it was their personalities as much as anything that made them into superstars.

But when we look back at them now, we see that they were actually pretty insufferable. They were great at upsetting out-of-touch parents and cultural authority figures; as a matter of fact, their parody of MTV’s hair-metal obsession in the “No Sleep Til” Brooklyn” video is one of the all-time best disses of pop culture’s gatekeepers. Even though they tried to play off their frat boy stereotype schtick as just having a good time, looking back at the group during this era is like revisiting your favorite John Hughes movies. We begin to realize that so much of 80s pop culture was really offensive.

Even the most charitable interpretations of “Girls,” “Brass Monkey,” and the “wiffle ball bat” line of “Paul Revere” don’t sit well today. At least Columbia forced the Beasties to change the album title from Don’t Be a F*ggot — yes, the group actually wanted this to be the name of the album. A mistake like that would have been impossible to redeem themselves from.

Of course, this was the 1980s and there’s always going to be a debate around how much we should excuse antiquated attitudes for being a product of a different time. This is especially true of the Beastie Boys, who for the rest of their career made it a priority to apologize for their offensive lyrics during this period. The most notable instance of this was MCA’s now legendary verse on “Sure Shot,” where he publicly repented for the group’s earlier sexism:

“I want to say a little something that’s long overdue,

The disrespect to women has to got to be through,

To all the mothers and sisters and the wives and friends,

I want to offer my love and respect till the end.”

This was a complete 180 for a group that were as famous for having go-go dancers and a 20-foot hydraulic penis on stage as they were for any talent they had. They should be celebrated for having the courage to throw away a large part of what made them successful — much easier said than done — in order to stand up for what’s right. In doing so, they laid the blueprint for how artists can mature in public without excusing the impact of their early mistakes.

3. The parody defense: Was this whole album just a joke that went over everyone’s heads?

Well, they kind of didn’t excuse their earlier mistakes — they were really duplicitous about the whole thing. As much as they apologized for Licensed to Ill, they equally justified their offensive behavior by saying that the entire album was simply a joke and that they were actually parodying the things they were rapping about. But if it was all a big satire, then why did they need to apologize?

They say while it started out as a parody, they were swept up in the hype and eventually became the very thing they were fighting against. In an interview with Tikkun, MCA said that “it wasn’t until “Fight for Your Right (to Party)” came out that we started acting like drunken fools… It started off as a goof on that college mentality, but then we ended up personifying it.”

Yet check out their video for “She’s On It” from the Krush Groove soundtrack, which came out before the band started writing for Licensed to Ill. Isn’t this the same exact thing they were doing on the album?

Of course, there is a lot of humor on the album. But to act like the entire album was some noble, progressive satire that was so convincing that even the group themselves fell for it is disingenuous at best. They were genuinely homophobic, as shown by a painful 1987 interview where Ad Rock and MCA explain and attempt to justify why New York City caused them to dislike gay people.

We should applaud the group for maturing, but if we excuse their early behavior as some well-intentioned parody that got out of hand, aren’t we doing a disservice to the band’s later growth?

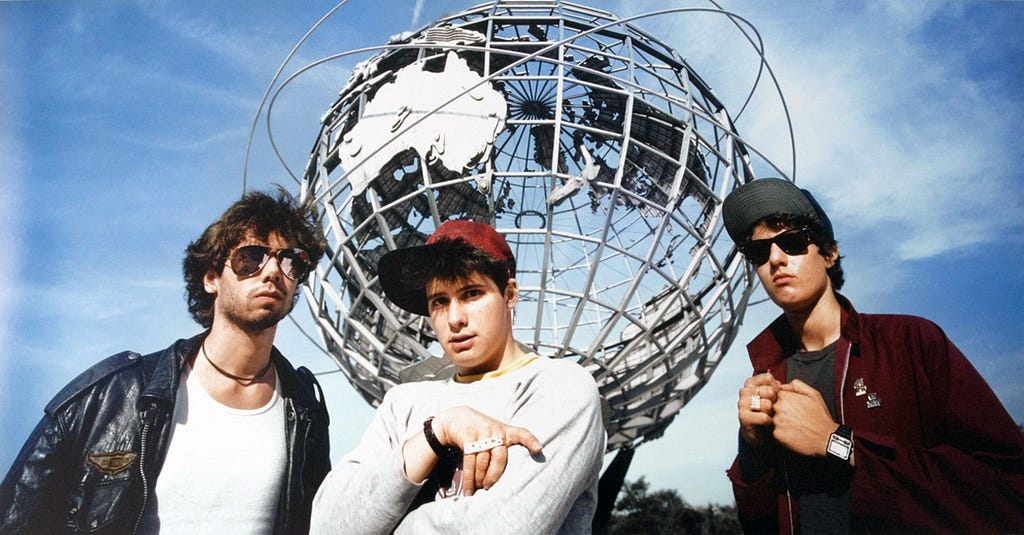

4. Despite being a trio of goofy white boys, they were completely embraced by the hip-hop community.

The Beastie Boys grew up in the burgeoning New York hardcore scene and as writer David Anthony points out, Licensed to Ill begins to make a lot more sense when viewed in that context. They combined the tough guy antics of the Cro-Mags with the drunken party anthems of Murphy’s Law and presented it in a hip-hop fashion. But before their dive into rap music, they were just another generic hardcore/punk band. It wasn’t until they put out the novelty rap record “Cookie Puss” in 1983 that they decided to completely drop the hardcore bit and go all in as rappers. Within three years they would become the biggest hip-hop group in the world.

Considering how new they were to hip-hop, it’s pretty incredible how they were universally embraced by the hip-hop community. In an underground scene like that of the early 80s, there’s usually a lot of bitterness for acts that blow up without paying major dues. And for it to be three Jewish kids that pretended to be gangsta rappers, it’s shocking that they weren’t shunned as culture vultures, especially after the incident at the Apollo when they were opening for Run DMC and Ad Rock jokingly shouted, “all you ni**ers, wave your hands in the air!”

And yet almost all the major players in New York hip-hop — everyone from Chuck D to Big Daddy Kane to DJ Red Alert — embraced them as one of their own. And they all give the same reason for why they were so beloved: they were true to themselves. They were three obnoxious Jewish boys and that’s how they personified hip-hop.

Again, I find this to be a little strange and not just because of the aforementioned tough guy, gun talk. Just looking at old pictures, it’s pretty clear that they very often copied the b-boy look again and again.

But despite what to me seems like the group obviously trying to fit in, we still praise them as bold trendsetters — just check out Chuck D and LL Cool J’s Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction speeches for the group. The way they gleefully talk about how the group broke down barriers while remaining true to their own spin on hip-hop makes me think I must be judging the group too harshly.

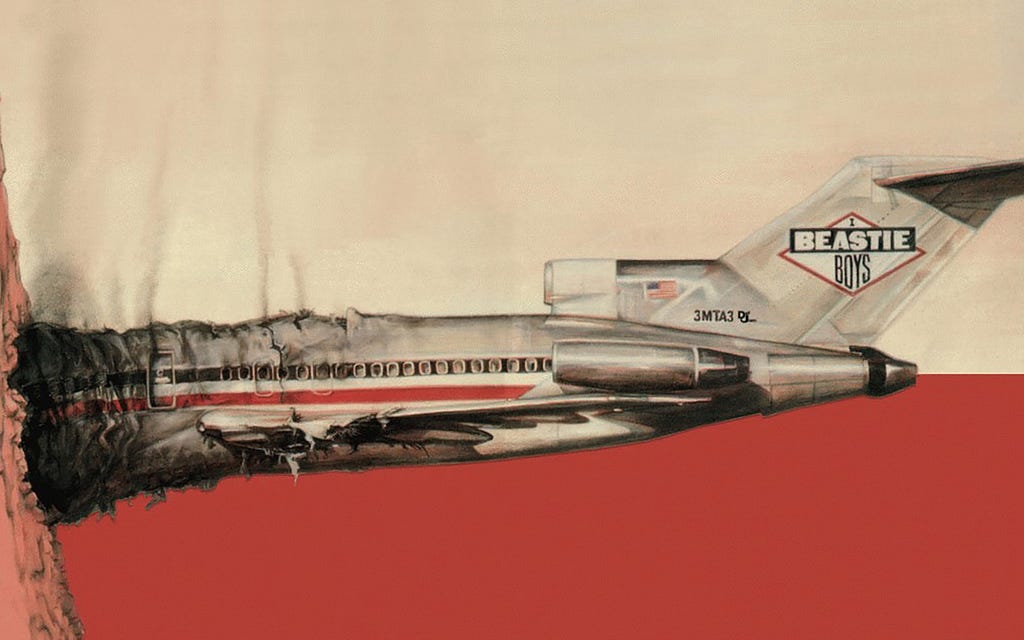

5. The album lives in the shadow of their later works, but was just as innovative

Whenever people talk about how important Licensed to Ill was, it seems to have less to do with the music itself. Instead, everyone focuses on the group’s personalities and their commercial appeal. And so far I’ve done the same thing. But because of the hype and popularity, this album doesn’t get its due when placed next to their later material.

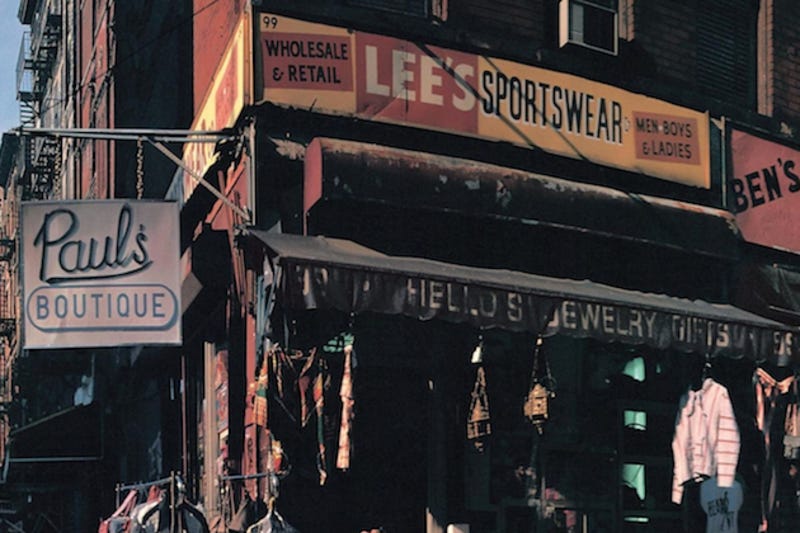

To many fans and critics, Licensed to Ill was the debut that, despite being a commercial sensation, is really just a product of its time. It’s a fun — yet dated — mid-80s Def Jam record. Then out of nowhere, they split from Def Jam’s control and matured into true artists by dropping their frat boy schtick and hooking up with the Dust Brothers to create a wildly creative masterpiece in Paul’s Boutique. And as the story goes, the band would continue experimenting for the rest of their career, never to return to the generic and immature style of Licensed to Ill.

In many ways, it makes sense why the album has become thought of as just a product of its time. Rick Rubin’s beats often sound like any other album that he produced from that era, most notably LL Cool J’s Radio. And although “No Sleep Til’ Brooklyn” and “Fight For Your Right,” were groundbreaking in the sense that they brought hip-hop to a new fanbase, creatively speaking they were really nothing new — Run DMC had already been using metal riffs for a few years on songs like “Rock Box” and “King of Rock.” This only feeds the narrative that the group was artistically riding Run DMC’s coattails, popularizing the Hollis, Queens trio’s style for a white audience.

But if we look beyond the surface, Licensed to Ill was actually a really innovative album — only a few hip-hop artists like Doug E. Fresh and Mantronix were making such experimental hip-hop at the time. There’s the amazing “Hold it Now, Hit It,” one of the strangest hip-hop singles of the period; “Paul Revere,” a fake western origin story propelled by a backwards sampled loop; and “Rhymin’ and Stealin,’” which contains the legendary, yet super-random bridge that has the group screaming “Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves” over and over. This is by no means a normal hip-hop album.

Licensed to Ill doesn’t get looked at as a creative breakthrough because it’s unfairly judged against the rest of the band’s catalogue and not appreciated on its own terms. Of course, Paul’s Boutique was creatively groundbreaking, but that doesn’t mean that what preceded it is therefore generic. Both albums were extremely progressive in their own ways, but because hip-hop as a whole progressed by leaps and bounds between 1986 and 1989, Licensed to Ill looks basic in comparison. But they didn’t simply go from immature idiots to musical geniuses by the time Paul’s Boutique came out, like many would have you believe. Ad Rock, MCA and Mike D were always extremely creative and simply took the experimentation they learned on Licensed to Ill to another level as they moved on from Def Jam.

To see more of Matthew Reyes’ work, check out his website The Earlier Stuff, where he explores the fun, interesting, and occasionally weird world of music.

Licensed to Ill: The Beastie Boys’ Complicated Legacy was originally published in Cuepoint on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Powered by WPeMatico