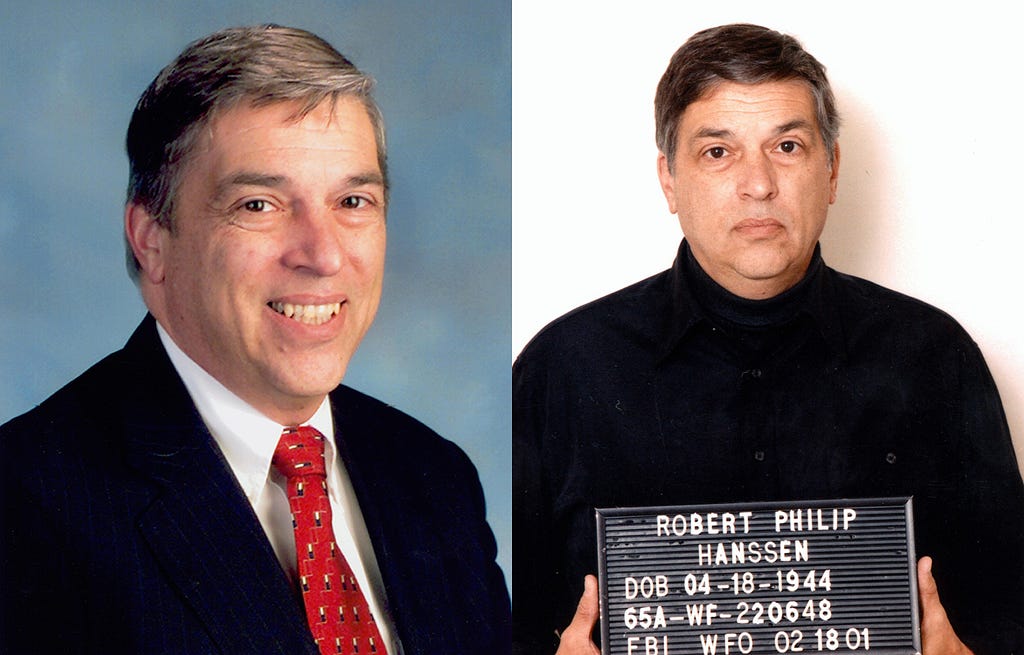

There was a Russian spy in the FBI for 15 years, and even he warned of election tampering

Starting in the Reagan Administration, Robert Hanssen was a mole

On February 18, 2001, after Robert Hanssen returned his visiting friend to the airport, he drove back toward home in Vienna, Virginia and stopped at Foxstone Park. He stuck a piece of white medical tape on the sign outside the entrance of the park. Hanssen then walked through the cold park to a wooden footbridge and placed a sealed black garbage bag in a secret spot near the base of the bridge.

In a matter of moments, Hanssen briskly, but inconspicuously, darted back to his car. But before he could reach it, he was swarmed by a team of FBI officers who were pointing guns in his face and yelling, “Freeze!”

As the FBI agents clapped handcuffs on Hanssen, he had only one question: “What took you so long?”

So long, indeed.

Hanssen had already been caught spying once for the Soviet Union, just three years after he joined the FBI in 1976. But it wasn’t the intelligence community that caught him. It was his wife, Bonnie, who discovered that he was dealing with the Russians after finding him scurrying to cover up some documents in the basement of their home. When she pressed Hanssen, he told her that “he was just tricking the Russians and feeding them false information,” she later told The New York Times. “He never said he was spying. I told him I thought it was insane.”

But Hanssen, who had recently been assigned to the counterintelligence unit to focus on Soviet activity, was not tricking the Russians. He was a Russian spy and had been working for Soviet military intelligence since 1979. In that short time, he had already sealed the fate of Gen. Dmitri Ployakov, one of the most important agents to the United States, who had been spying for the American intelligence community since the early 1960’s. Soon after Hanssen informed the Russians, Polyakov was forced into retirement and later executed.

As a conservative Roman Catholic, Bonnie Hanssen demanded they see a priest to discuss Robert’s activity. Robert P. Bucciarelli, a priest affiliated with Opus Dei, a conservative Catholic organization they had joined several years earlier called on Hanssen to donate the money from the Soviets to charity, vow not to spy again and confess his sins and ask God for forgiveness. Do these things and and the Hanssens would have Bucciarelli’s blessing to not report the matter to the FBI.

Although Hanssen had spent most of the $30,000 he received from the Soviets by that point, he began making small payments to a charity affiliated with Mother Teresa’s Catholic charity. The debt Hanssen was repaying nearly bankrupted the family of eight, but he assured Bonnie that he was making good on the plan.

On October 4, 1985, Hanssen sent a letter addressed to a KGB officer in Washington, DC. Inside was another one marked “Do not open. Take this envelope unopened to Viktor I. Cherkashin.”

Cherkashin, Moscow’s chief counterspy at the Soviet embassy, was a KGB colonel adept at handling double agents. Inside that second envelope was an anonymous offer to send a trove of classified papers to the KGB in exchange for $100,000. It also proposed a plan to keep selling similar secrets.

“They are from certain of the most sensitive and highly compartmented projects of the U.S. intelligence community,” wrote the sender, who identified himself as “B.” “All are originals to aid in verifying their authenticity.”

“B” also named three KGB officers who had been recruited by the U.S. Soon after, the three officers were recalled to Moscow where two were executed and one placed in a labor camp. That initial communication sparked sporadic exchanges of information and cast between Hanssen and the KGB that lasted until December 1991.

Hanssen was particular about how he should be addressed and how he would conduct his business. He used other aliases, such as Ramon Garcia and Jim Baker, but his handlers were instructed to only address him as “Dear Friend.” When Moscow contacts suggested different drop sites or to meet Soviet agents face-to-face, he declined. “I am much safer if you know little about me,” he wrote in 1988. “Neither of us are children about these things. Over time, I can cut your losses rather than become one.”

By 1991, Hanssen began to feel he could become one of those losses and cut ties with his Moscow contacts, making his double agent persona dormant for 8 years. In 1999, he made contact once again, but different power dynamics with new players were in place after the fall of the Soviet Union — a condition Hanssen had not properly navigated.

A disgruntled Russian intelligence operative provided the FBI with a fingerprint Hanssen left on one of his dead drop black garbage bags, as well as a tape recording from one of his rare phone calls with a Russian agent. The FBI also obtained the complete original dossier the KGB had on Hanssen.

In 2000, the FBI began a full surveillance operation against Hanssen. Part of the scheme was to give him an obscure assignment with a small team who knew it was a mole hunt. Counterintuitively, that meant giving Hanssen access to more classified and top secret information to see if that would cause him to slip up.

In all, by the time he was arrested in February 2001, Hanssen collected an estimated $1.4 million for giving lists of American undercover agents abroad, the identities of Russian double agents, documents showing the U.S. was intercepting Soviet satellite transmission and the methods by which the U.S. would retaliate in the event of a nuclear attack.

On May 16, 2001, Hanssen was indicted on 21 counts of spying for the Soviet Union and Russia. After initially pleading not guilty to all charges, he avoided the death penalty in a plea bargain that included a life sentence without the possibility of parole.

“It’s astonishing that the very guy who was going after dissenters was in fact working for the Soviets,” said Michael Ratner, vice president of the Center for Constitutional Rights, a group that had been monitored by the FBI during Hanssen’s tenure.

But why did he do it?

“Fear and rage,” Hanssen told his investigators. “Fear of being a failure and fear of not being able to provide for my family.”

Hanssen said he had “rage” toward the FBI each time he was denied a promotion and was determined to prove they had made a mistake in not promoting him by pulling off increasingly large-scale feats of espionage. Hanssen was plagued with an outlook that other FBI agents lacked his commitment and the bureau itself which, in his view, was not fighting the Russians the right way.

Ironically, his FBI reports on Soviet influence became increasingly alarming. One 1998 FBI report with Hanssen’s initials on it warned that Moscow specifically had sought to recruit U.S. doctors, astronauts, and congressmen, even suggesting that Moscow even might look to meddle in upcoming presidential elections.

“It is possible that the Soviet Union will institute a new series of active measures operations designed to discredit those candidates who have platforms that are not as acceptable to the Soviet government as those of other candidates,” the report states.

Far-fetched.

There was a Russian spy in the FBI for 15 years, and even he warned of election tampering was originally published in Timeline on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Powered by WPeMatico