This amazing woman is the forgotten architect of the American Social Security system

You can thank her for your retirement benefits

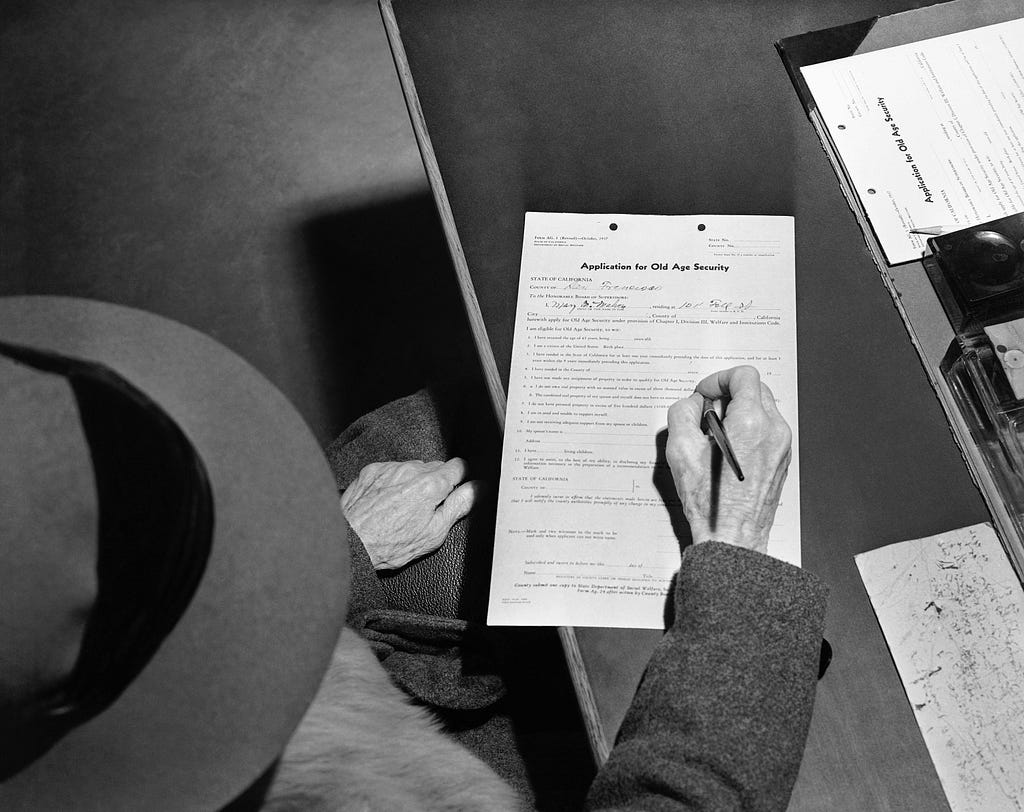

In the early 1930s, homeless Americans were picking food scraps off the street and cooking over oil drums in shantytowns. At one point, the unemployment rate reached an all-time high of 25 percent. The country needed new leadership, a plan for healing. It elected President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, whose New Deal ushered in many successful programs, not the least being Social Security. That’s where Barbara Armstrong stepped in.

Her theories on economic security formed the backbone of one of America’s most successful social benefit programs. Social insurance, she felt, should be a universal right enjoyed by all — without an expiration date. Today, it’s one of the reasons Baby Boomers are off kiteboarding in Florida.

Before she became the first female law professor in the country and a drafter of the Social Security Act of 1935, Barbara Armstrong (nee Nachtrieb) was born in San Francisco in 1890. She grew up the third of four children. By 1913, she had earned her BA from the University of California at Berkeley, and her law degree two years later from the university’s Boalt Hall — one of two female graduates that year.

For two years, she split time taking on occasional cases and working as executive secretary for the California Social Insurance Commission. There, she studied worker’s compensation and other government-sponsored poverty solutions, which inspired her return to school for a Ph.D. in economics. In 1921, she earned her doctorate while at the same time working as the first tenure-track female faculty member at a law school approved by the American Bar Association.

Armstrong was beloved by students and faculty alike. She worked diligently as a lecturer and later as an assistant professor in both the law and economics departments at Berkeley. She was an ardent feminist whose early interests in social insurance preceded popular theory by years. Many of these ideas she had studied during academic travels to Europe between 1926 and 1927. When she returned home, Armstrong synthesized the social insurance applications of 34 different industrial countries into Insuring the Essentials: Minimum Wage Plus Social Insurance — A Living Wage Program in 1932. Not exactly a rollicking read, but an important work. In it, she concluded, “Except in the field of industrial accident provision, the United States is in the position of being the most backward of all the nations of commercial importance in insuring the essentials to its workers.” The book astounded Washington with its theories on unemployment, disability, health care, and retirement.

In 1928, Boalt Hall hired Armstrong as an associate professor full time. She was promoted to professor after seven years, longer than most of her male colleagues. She was also paid less. Her dean — who presumably wasn’t in charge of compensation — reportedly said no professor should earn so little.

In the throes of the Great Depression, Armstrong put forth progressive hypotheses about the obligations of industrialized nations to the economic well-being of their citizens. This drew the attention of FDR, who in 1934 invited Armstrong to work as Chief of Staff for Social Security Planning, on the Committee on Economic Security (CES). Suddenly, she moved from advocating radical reform to writing actual legislation.

Prior to Roosevelt, U.S. presidents were expected to steer clear of Wall Street interests. President Herbert Hoover had formed a conservative belief in small government that would define his approach to Depression Era economics, which offered no immediate or major federal intervention. Instead, he called upon states to regulate minimum wage and private charities to help solve the nation’s poverty.

Meanwhile, conditions around the country worsened. By 1931, the unemployment rate hit 15.8%. Homeless families scavenged in makeshift shantytowns (sardonically known as Hoovervilles). Still, Hoover refused to involve the government by fixing prices or controlling currency, which he feared would lead to socialism. Instead, he emphasized aid through private volunteerism and charitable works. He asked employers not to cut wages. He suggested neighbors help each other. He believed the economy relied chiefly on morale, and that it would self-correct.

When it didn’t, the country elected FDR, who believed an aggressive federal intervention was needed. He surrounded himself with people like Armstrong, who had studied social insurance for years.

Armstrong was attuned to politics. According to Nancy Altman, author and president of Social Security Works, she was an “infighter” whose outspokenness convinced the CES to propose a federal program that addressed old age insurance. With the help of Labor Secretary Frances Perkins, the first woman appointed to the U.S. Cabinet, the Social Security Act of 1935 passed. “There were a lot of very strong women who surrounded Roosevelt at the time,” says Altman.

Granted, the act had its flaws, one being that participants wouldn’t see the first monthly benefits until 1942. Republicans argued that building up reserves amounted to IOUs and warned people would have to start paying taxes. Many of the act’s original proposals, such as the inclusion of agricultural and domestic workers, were “temporarily” thrown out due to implementation difficulties. Armstrong supported excluding the groups for these reasons, though Altman insists critiques around gender and racial bias are unfounded. A series of reforms in 1939 expanded Social Security benefits to include family dependents, wives, and widows — but no benefits for dependent men, who were presumed to be in the workforce.

“The 1939 legislation changed the basic nature of the program from that of a retirement program for an individual worker, to a family-based social insurance system (based on the then-current model of the family, in which the man was the breadwinner with a nonworking wife who cared for the minor children),” according to the Social Security Administration today.

The first person to become a Social Security beneficiary was Ida May Fuller, who, upon retiring as a legal secretary in November of 1939 at age 65, received her first benefit on January 31, 1940 — a monthly check for $22.54 (an amount equal to $389 today).

In 1950, the Social Security Advisory Council demanded further expansion. Congress brought 10 million additional workers under coverage, mainly self-employed, domestic, and agricultural workers; disabled workers were added in 1957. The goal was universal old-age and disability security (and actually, was initially designed with universal health care in mind). Today, about 93 percent of working Americans pay taxes into the Social Security program. By June of 2016, one in six Americans was collecting, at an average of $1,350 per month.

Barbara Armstrong returned to Berkeley after the initial Social Security Act of 1935 passed, long before Social Security’s many additional reforms. She had clashed with a few cabinet members — she reportedly called CES executive director Ed Witte “half-Witte” behind his back. Alas, she had a professorship, a daughter, and new issues to tackle back home. She taught courses on family and labor law, and in 1940, she and others attempted to introduce universal health insurance in California, but failed. On campus, Armstrong was a respected, passionate, opinionated, and witty presence. She supported other female staff through the Women’s Faculty Club at a time when “most of the faculty thought of women as frankly inferior beings,” said Lucy Sprague Mitchell, the first dean of women at Berkeley.

In 1970, at age 79, Armstrong was still actively teaching at Boalt Hall. That year, she was attacked by three unknown men while walking in Berkeley. She spent the rest of her years in a wheelchair, and contributed studies in cooperative measures against crime. She died in her Oakland home on January 18, 1976.

This amazing woman is the forgotten architect of the American Social Security system was originally published in Timeline on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Powered by WPeMatico