This little-known American smuggled thousands of French Jews out of Nazi-occupied France

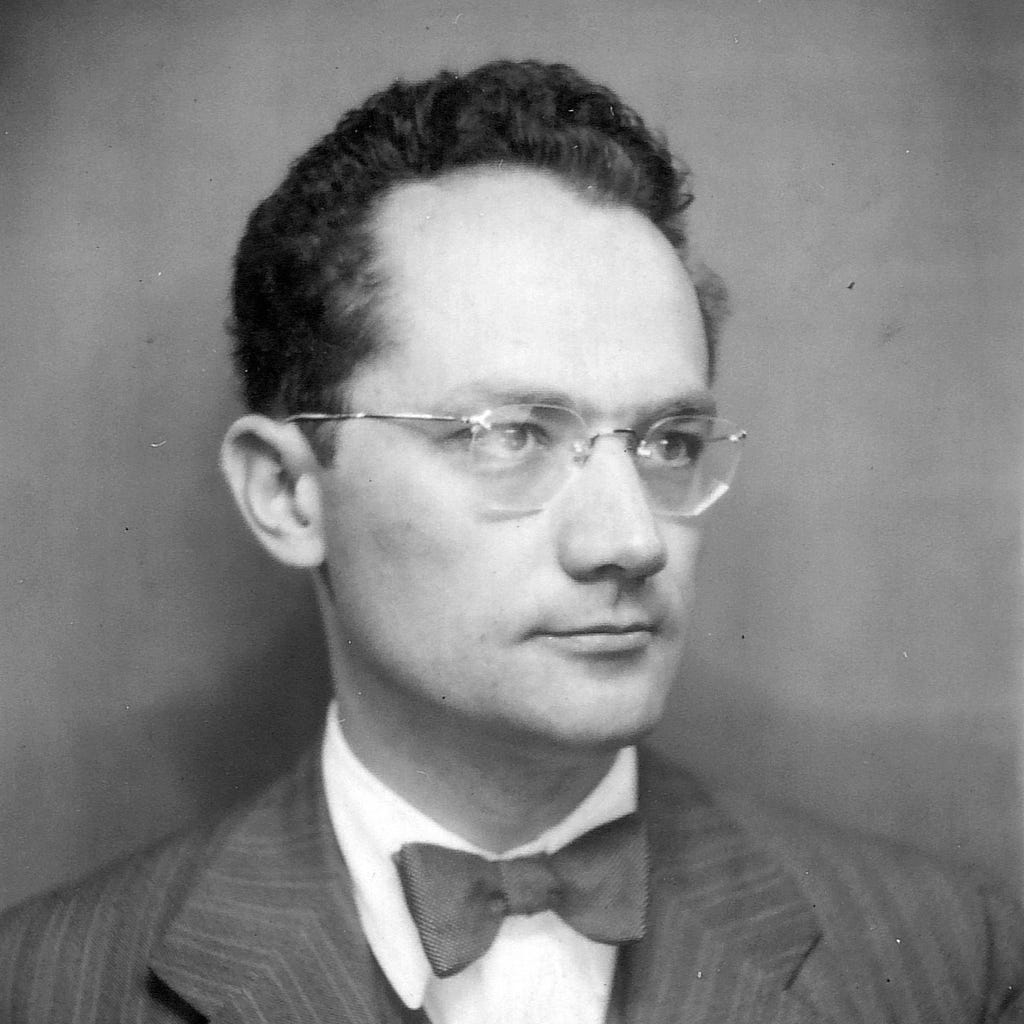

Varian Fry is often called the ‘American Schindler’

As the reach of Nazi power expanded, and terrified families scrambled to get out of Europe, a young American editor named Varian Fry headed directly into the action. Fry was a bookish Jersey boy and a born empath who had even organized a fundraiser for the American Red Cross during World War I — which included an ice cream stand and vaudeville show — at the tender age of nine.

Fry attended Harvard, where he started a literary journal, Hound & Horn, with his friend Lincoln Kirstein, a dynamic writer, thinker, and “cultural swizzle stick” who would go on to co-found the New York City Ballet. Through Kerstein’s sister, Fry met his wife, an Atlantic Monthly editor named Eileen Avery Hughes. Though he was kicked out of Harvard for planting a “For Sale” sign on a dean’s lawn, Fry managed to charm his way back in and graduated in 1931 with a degree in classics.

His German wasn’t great, but when the journal The Living Age wanted to send Fry to Berlin as a foreign correspondent in 1935, the “earnest young liberal” jumped at the chance. He arrived, according to biographer Andy Marino, “with a mission, and a fat, empty notebook” that quickly filled with notes on the Nazi frenzy, the “wildly cheering crowds…full of gleeful children waving their red and white flags with that sinister black spider at the center, their proud mothers smiling and waving to the bull-necked brownshirts strutting along.” Fry stayed in a hostel, the Pension Stern, where he met people like anti-Nazi lawyer Alfred Apfel — who was representing a man charged with setting the Reichstag Fire — and other endangered Jewish artists and intellectuals.

One balmy night in July, Fry witnessed a small riot on the street outside the hostel on the Kurfuerstendamm. In his 1945 memoir, Surrender on Demand, Fry would later call it the first great pogrom against the Jews. “I…saw with my own eyes, young Nazi toughs gather and smash up Jewish-owned cafés, watched with horror as they dragged Jewish patrons from their seats, drove hysterical, crying women down the street, knocked over an elderly man and kicked him in the face.” There was plain delight on the faces of the perpetrators. A child turned to Fry and said, “This is like a holiday for us.” Middle-aged couples out strolling on the promenade joined in the beatings. “When Jewish blood spurts from the knife, then things will get even better,” the mob shouted in a call and response Fry likened to a Christian liturgy.

In that instant, his life changed forever.

Fry wrote about what he’d witnessed in The New York Times, and became a staunch anti-Nazi journalist, working once he’d returned to the States to raise money for underground European anti-fascist movements. When France fell to the Nazis, Fry was one of a group of concerned activists and intellectuals who formed the Emergency Rescue Committee (ERC) with the specific aim of helping refugees in Vichy France who’d been displaced by the war and were in danger of being turned over to the Nazis. The group compiled a list of about 200 artists and intellectuals at risk of persecution and death.

Then, on August 4, 1940, the 32-year-old Fry, one of the most determined of the ERC’s founders, travelled from New York to Marseilles. He had the list of names, and $3,000 in cash strapped to his leg. He booked himself into a small hotel, where he planned to stay about a month, working with a small group of activists to help the Jews and non-Jews on his list gain safe passage out of France. “By the end of the second week,” he wrote in his memoir, “the crowds waiting outside my door were so large the management complained…A few days later, the police came by with the Black Marias and picked up the whole lot of them.” But more arrived, and then more. The number of people who needed his help was overwhelming.

Fry ended up staying in France 13 months. But French authorities were onto him — he was under constant surveillance — so rather than pursue any visas through legal channels, he began, with the help of a network of activists, hiding those in imminent danger, and smuggling them to freedom.

In 1941, Fry was forced by both the Vichy and American governments to return to the U.S. By then, he had helped thousands of Jewish or anti-Nazi refugees escape—estimates range from 2,000 to 4,000. Among them were Hannah Arendt, André Breton, Marc Chagall, Max Ernst, Claude Lévi-Strauss, Victor Serge, and others who would go on to make extraordinary contributions in arts and letters, not to mention the many others who would go on to simply live.

The ERC office was raided and closed in 1942. That same year, Fry wrote “The Massacre of the Jews,” an unflinching piece that appeared in The New Republic and was one of the first accounts of the Nazi extermination campaign to appear in the American press. “The program is already far advanced,” he wrote, beseeching readers not to turn a blind eye to what he called “the most appalling picture of mass murder in all of human history.”

As those who are drawn to war and conflict often note, there is a perverse fun to be had in high-stakes living, even when it’s life-and-death. As another biographer, Sheila Isenberg, wrote in A Hero of Our Own: The Story of Varian Fry, ‘’It sometimes seemed as if Fry was hosting a giant party.” An intellectual himself, he had a penchant for cavorting with artists, writers, and activists over big meals, even as the Gestapo was closing in. ‘’There’s a hell of a lot of fun — though that’s not quite the word — in rescue work,” Fry said. “It’s stimulating to be outside the law…And as for depression, anxiety — all that pattern simply vanishes.’’

That pattern came back, however. After years of living anxiously but ebulliently under the watch of the Nazis, and working nobly toward something he believed was vitally important, Fry struggled to re-assimilate to life in the U.S. He worked as an editor at The New Republic, and published his memoirs after the war concluded, but his marriage disintegrated, and a subsequent union also ended in divorce. He suffered from depression, and claimed to have grown more troubled as time went on, feeling from a rather young age like his best days were behind him.

Though France awarded him the Legion of Honor in 1967, five months before his death, the U.S. did not formally recognize Fry’s heroism until 2007, the 100th anniversary of his birth. He was also posthumously listed in Israel’s Righteous among Nations, a list of non-Jews who risked their lives to help Jews during the Holocaust, an honor he shares with Oskar Schindler.

This little-known American smuggled thousands of French Jews out of Nazi-occupied France was originally published in Timeline on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Powered by WPeMatico