This white reporter from Pittsburgh dressed like a black man for 30 days to expose Southern racism

The new book ‘30 Days a Black Man’ looks back at his story

In 1948, a white, Pittsburgh-based journalist named Ray Sprigle laid out in the punishing Florida sunshine far longer than is advisable, and got himself a screaming sunburn. He did it on purpose. The burn was painful, and his skin came off in sheets. But a couple days later the redness yielded to a deep, dark tan. With his new coloring, thick-framed black glasses, and a freshly Bic-ed head, Sprigle traveled to the Deep South to pretend to be black for a month.

A veteran newsman, Sprigle enjoyed donning disguises and disrupting the status quo. During World War II, he’d posed as a butcher to expose a black market meat racket. In 1938, he won a Pulitzer Prize for investigative work revealing that U.S. Supreme Court Justice Hugo Black, newly appointed by President Franklin Roosevelt, was a member of the Ku Klux Klan.

In posing as a black man, Sprigle was looking to experience the racism of the Jim Crow South firsthand, and bring back to readers an honest depiction of both the injustices black Americans faced, and the flowering of black culture in spite of that brutal reality. In an exhaustive new book, 30 Days a Black Man, journalist Bill Steigerwald chronicles Sprigle’s journey, exploring the context that made his record of the experience such a powerful document.

Sprigle spent four “endless, crawling” weeks traveling through the South in a dark green Mercury. He wasn’t alone. Knowing his mission would require the mentorship and cooperation of an actual black man, Sprigle reached out to the NAACP, and was connected with John Wesley Dobbs, a formidable Atlanta activist, who accompanied him on the trip. Before departing, Sprigle got an education from Dobbs in how to conduct himself as a black man. The lessons can be distilled to: don’t talk back, hit back, fight back, or forget to say Sir or Ma’am. Don’t use the wrong door, seat, or water fountain. If you bump into a white woman, back away apologizing. Never defend yourself.

Nothing could have prepared Sprigle for what he experienced. For one thing, he was surprised that his blackness was only questioned twice during the journey. But, he realized, no one in their right mind would try to “pass” in the direction he was; it would be senseless to willingly choose second-class citizen status. It also became immediately clear that the spectrum of skin tones was far broader than he thought. He was struck by what that meant, the generations of rape and what was then called “miscegenation.” “Looks to me from where I sit, as just another light-skinned one of millions of other light-skinned Negroes,” he wrote, “that the noble white man got hold of this racial purity thing a little late. Where does he think these millions of white, light, and brown Negroes came from? Think the stork found ’em somewhere?”

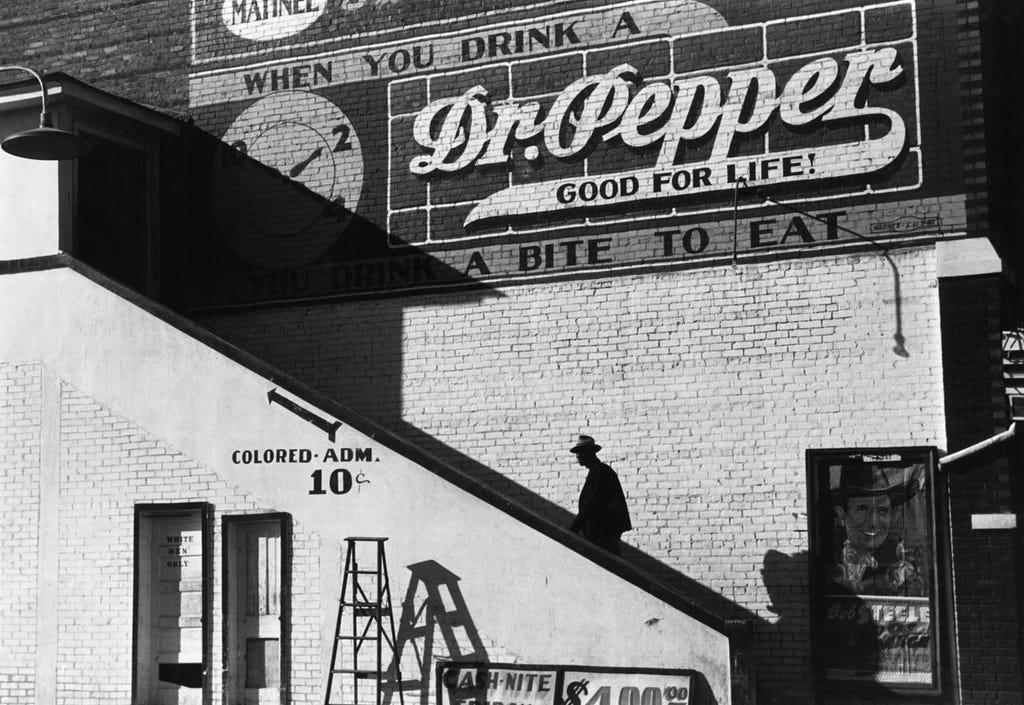

Sprigle lived among Southern black people. “I ate, slept, traveled, lived Black,” he wrote. “I lodged in Negro households. I ate in Negro restaurants. I slept in Negro hotels and lodging houses. I crept through the back and side doors of railroad stations. I traveled Jim Crow in buses and trains and street cars and taxicabs. Along with 10,000,000 Negroes I endured the discrimination and oppression and cruelty of the iniquitous Jim Crow system.” He wrote that he sat for long hours in groups of black people “where we discussed everything from Shakespeare to atomic energy and the price of cotton.” He hung out in shotgun shacks talking to sharecroppers, learning the impossible economic calculus of that particular injustice. He also talked to tenant farmers, businessmen, clergymen, doctors, dentists, and nurses, attendeding picnics (he described the food rapturously), church services, and meetings at Masonic temples. He heard stories of violence and death, fear and struggle, and called the racism he encountered both “heartbreaking” and “plain silliness.” From the very first day of his journey, Steigerwald writes, Sprigle “found himself feeling contempt for the white race.”

“I Was a Negro in the South for 30 Days,” the resulting 21-installment series published in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette is a study not only of American race relations, but a window onto a particular white, Northern sensibility halfway through the last century. What Sprigle recorded, of course, was filtered through his particular assumptions about what he’d find. For example, that anything he witnessed was surprising at all, well, he had to be white to find it so.

Many white readers did find Sprigle’s exposé shocking. As Steigerwald writes, the work was unprecedented. “It was daring. It was openly biased. It was accessible. And everyone who read it could tell Sprigle was genuinely appalled by what he had seen and experienced.” The Post-Gazette was flooded with mail. The Pittsburgh Courier, the city’s black paper, also ran the series. Eleanor Roosevelt was among Sprigle’s fans, and she penned a letter saying, “The subtle way in which this reporter’s feelings changed and he began to dislike his own kind…is very enlightening.” Steigerwald argues in his book that Sprigle’s series was instrumental in paving the way for legislation like Brown v. Board of Education in 1954.

As historian Juan Williams points out in his introduction to 30 Days a Black Man, Sprigle wasn’t the first to try something like this. In 1859, Mortimer Thompson, a New York Tribune writer, posed as a slave buyer in order to attend a Savannah, Georgia slave auction, chillingly concluding that for families, “the separation is…more hopeless, than that made by the Angel of Death.” Racial reversals have long captured the American imagination. Thirteen years after Sprigle’s work, another white journalist, John Howard Griffin, achieved celebrity status for undertaking a similar project and writing about it in Black Like Me.

Such experiments reveal an impulse to get at some deeper truth of racialized experience, to play with, revise, or take apart these arbitrary designations from the inside. But they also reveal their own impossibility. While race may be a biological fiction, it is a social reality. And though social scientists have long demonstrated the utility of ethnography, we must also acknowledge that one cannot, in the truest sense, “become” a black man.

The ease of Sprigle’s prose, his occasionally disconcerting playfulness, as when he discusses failed attempts at darkening his skin with walnut juice, his willingness to take certain risks, like walking through the “White” entrance of a railroad station just to see what would happen, serve as a reminder that he possesses the ability to move fluidly and temporarily between these worlds, but only because of his race. The opinions he forms only find a platform because of his race.

As one Ms. Hawk, proprietress of a YMCA Sprigle visits, commented later to Dobbs, “That friend of yours — he talks too much to be a Negro. I think he’s white.”

Bill Steigerwald’s 30 Days a Black Man is out now from Lyons Press.

This white reporter from Pittsburgh dressed like a black man for 30 days to expose Southern racism was originally published in Timeline on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Powered by WPeMatico