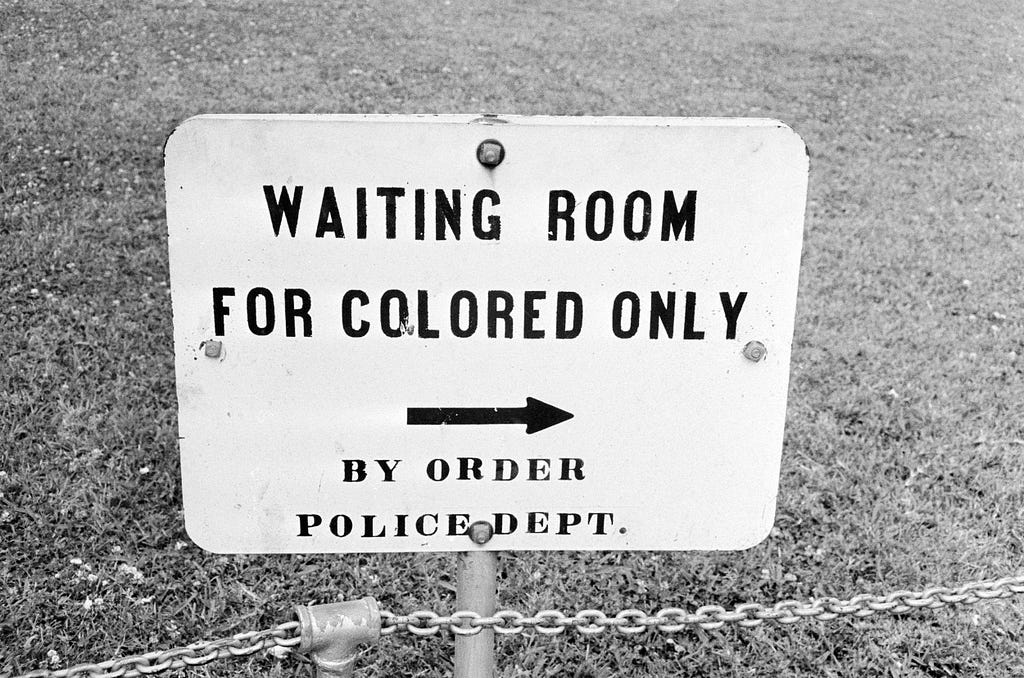

On the quiet Sunday morning of August 3, 1952, Ruby McCollum, the richest black woman in the town of Live Oak, Florida, put two of her children in the backseat of her blue Chrysler. She then drove to the office of Clifford Leroy Adams, a prominent white doctor and state senator-elect. She parked, walked in the “colored entrance” and through the office waiting room. She pulled a .38 caliber pistol from her pocketbook, and shot the doctor dead.

White townspeople would say that McCollum was trying to dodge a medical bill, but McCollum would claim that she’d been sexually victimized by the doctor for years, and forced to bear his child. The murder and the national attention garnered by the subsequent trial brought to light the open “secret” of rape in the South, and dredged up many other issues the town of Live Oak had long kept buried.

Halfway between Tallahassee and Jacksonville, Live Oak was sleepy and serene. A straightlaced, segregated town, it was the kind of place that was pleasant for white families and much less friendly to others. As historian Carol Herring says in the 2012 documentary The Other Side of Silence: The Untold Story of Ruby McCollum, “This part of North Florida is the deepest of the Deep South.” Rodney Hurst, an author and civil rights activist, corroborates that for nonwhites, Live Oak “was not a town that you wanted to travel to or through, and you didn’t want to spend the night there.” Eight years before Ruby McCollum turned a gun on Clifford Adams, a 15-year-old named Willie James Howard was lynched for sending a Christmas card to a white girl. (The girl was the daughter of a state legislator, who came for the boy personally and may have been the one to kill him.)

By all accounts, the town of Live Oak all but screeched to a halt after Ruby McCollum pulled the trigger that August. “Dr. Adams Slain by Negress,” read the headline in the local paper the following day. People speculated about McCollum’s motives — there were rumors she and Adams were lovers — and black residents feared reprisals by the KKK. As C. Arthur Ellis and Leslie E. Ellis write in The Trial of Ruby McCollum, Live Oak residents gathered at beauty shops and lunch counters the following day to express their shock and grief over the sudden death of the kind “poor man’s doctor,” but “public lamentations soon gave way to whispers about Adams’ darker side.” Was Adams involved in illegal business with McCollum and her husband? Might he have owed her money? Did Adams’ rumored habit of overprescribing morphine contribute to McCollum’s state of mind that day?

Newspapers from all over the country reported on the sensational McCollum trial. The Pittsburgh Courier, one of the most widely distributed black newspapers in the country — at the height of its popularity, as many as 14 editions circulated nationally — sent novelist and anthropologist Zora Neale Hurston to cover it. The judge, who was a pallbearer at Dr. Adams’ funeral, imposed a gag order on McCollum, prohibiting her from giving interviews. Furthermore, the press was barred from the courtroom. But Hurston sat daily in the segregated balcony, scribbling the notes that became “The Life Story of Ruby McCollum,” a multi-installment report. In it, she wrote with nuance about not only the testimonies, but the underpinnings of racial prejudice that warped the entire proceeding.

Ruby was married to an industrious man named Sam McCollum, who, along with his brother Buck, ran a highly profitable gambling ring. The family also sold liquor, grew tobacco on a nearby farm, and owned a couple of juke joints. The couple was known by nearly everyone in town. They lived in a two-story house, where they raised four children, one of whom was studying at UCLA at the time of the murder. During her trial, Ruby testified that the youngest, Loretta, was the child not of her husband Sam, but of Dr. Adams. She claimed the doctor had raped and assaulted her for years, forced her to bear his child, and threatened to kill her if she didn’t bear him another. Hurston wrote that the judge repeatedly shut down efforts by Frank Cannon, McCollum’s lawyer, to ask her for details about the violence. “Ruby was allowed to describe how, about 1948, during an extended absence of her husband, she had, in her home, submitted to the doctor,” Hurston wrote. “She was allowed to state that her youngest child was his. Yet thirty-eight times Frank Cannon attempted to proceed from this point; thirty-eight times he attempted to create the opportunity for Ruby to tell her whole story and thus explain what were her motives; thirty-eight times the State objected; and thirty-eight times Judge Adams sustained these objections.”

It seemed clear to many that Loretta was Dr. Adams’ daughter, but that meant to jurors that the wealthy woman and the 44-year-old, 270-pound doctor were simply lovers. In the documentary You Belong To Me: Sex, Race, and Murder in the South, Tameka Bradley Hobbs, a professor of history at Florida Memorial University, says Loretta “looked a lot like her father, so just visually it was very difficult for anyone to escape or deny that this was Doc Adams’ child.” Adams’ secretary, Thelma Curry, said that McCollum was a frequent visitor to the doctor’s office. And in a 1960 interview with Jet magazine, McCollum told an interviewer that the morning Dr. Adams delivered Loretta, he’d called her husband Sam “into the bedroom and told him: ‘Sam, I love all my children — niggers and white — and this is my baby. I want you to treat it right and see that it gets proper care.’”

The prosecution alleged that McCollum was haggling over a $116 medical bill the morning she shot and killed Adams. And indeed, Thelma Curry testified that she heard the two discussing money. But the focus on the payment was also a means of diverting attention away from the charge of sexual violence. According to Hurston, “It was like a chant. The medical bill as a motive for the slaying was ever insisted upon and stressed….there was this quick and stubborn insistence that the medical bill, and that alone, could have been the cause of the murder. It was obviously a posture, but a posture posed in granite.”

Of course, a man like Clifford Adams — white, elected to public office, celebrated in his community, and gunned down in the prime of his life — was about as sympathetic as a character could be in the 1950s Deep South, especially to jurors a lot like him. But the charge that Adams had raped McCollum, and its repetition throughout the trial, made the case bigger than one man’s reputation, bigger than any lone woman carrying out a solitary act of insanity or revenge. McCollum’s testimony — reportedly the first time in history that a black woman accused a white man of sexual assault in open court — served as a broader indictment of “paramour rights,” the widespread practice among white men of having sexual relationships with black women by force or coercion. Those relations, while certainly never mentioned in polite company, had tacitly become so normalized as to be nearly invisible. The proliferation of mixed-race children in the South was the result of such encounters, but like so many ugly realities borne of slavery, it was simply too fraught, too painful, or too uncomfortable to acknowledge. And needless to say, the men involved had no interest in publicity.

Hurston was no stranger to unease around this subject: she had written about the phenomenon before. In the capacity of anthropologist, she’d spent time in the 1930s in the turpentine camps of North Florida, and documented there the practice of white men subjecting black women to sexual relationships, coining the term “paramour rights.” So, it was with the life experience of a southern black woman and a particularly keen ethnographic eye that she took in the McCollum trial. That expertise enabled her to painstakingly report on not just the details but the stakes of the trial.

In pulling the trigger that day, Ruby McCollum exposed the seedy underbelly of pastoral Live Oak — including gambling, prostitution, illegal liquor sales, and the cops and officials who were paid off in cash to keep their mouths shut, as well as the existence of relationships, sexual and otherwise, that crossed the color line. She also surfaced a dark truth about white men. Though they would continue to lay claim to the bodies of black women, with relative impunity in many cases, historians mark the trial as a turning point in the national consciousness. Even if the legal system or the culture at large were slow to catch up, it was a bell that couldn’t be unrung.

As for McCollum, the jury of white men sentenced her to death by the electric chair at the trial’s end in 1953. She escaped that fate when her case was appealed and overturned on a technicality by the State Supreme Court, and when it was brought before the court again in 1954, McCollum was deemed mentally incompetent to stand trial. She was sent to the notorious Florida state mental hospital at Chattahoochee, where she resided until 1974, when her lawyer was able to arrange for her release. When interviewed in 1980, McCollum had no recollection of the shooting or its aftermath, which aroused suspicion that she’d been subjected to electroshock therapy while committed. She died in 1992.

When this black woman shot a white doctor in the 1950s, an ugly Southern secret came to light was originally published in Timeline on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Powered by WPeMatico