When this group of black mothers locked themselves in a government office, Boston erupted in riots

It was the beginning of the Long Hot Summer of 1967

The women of Roxbury were tired of being disrespected. Tired of being called names. And tired of being watched by the cops.

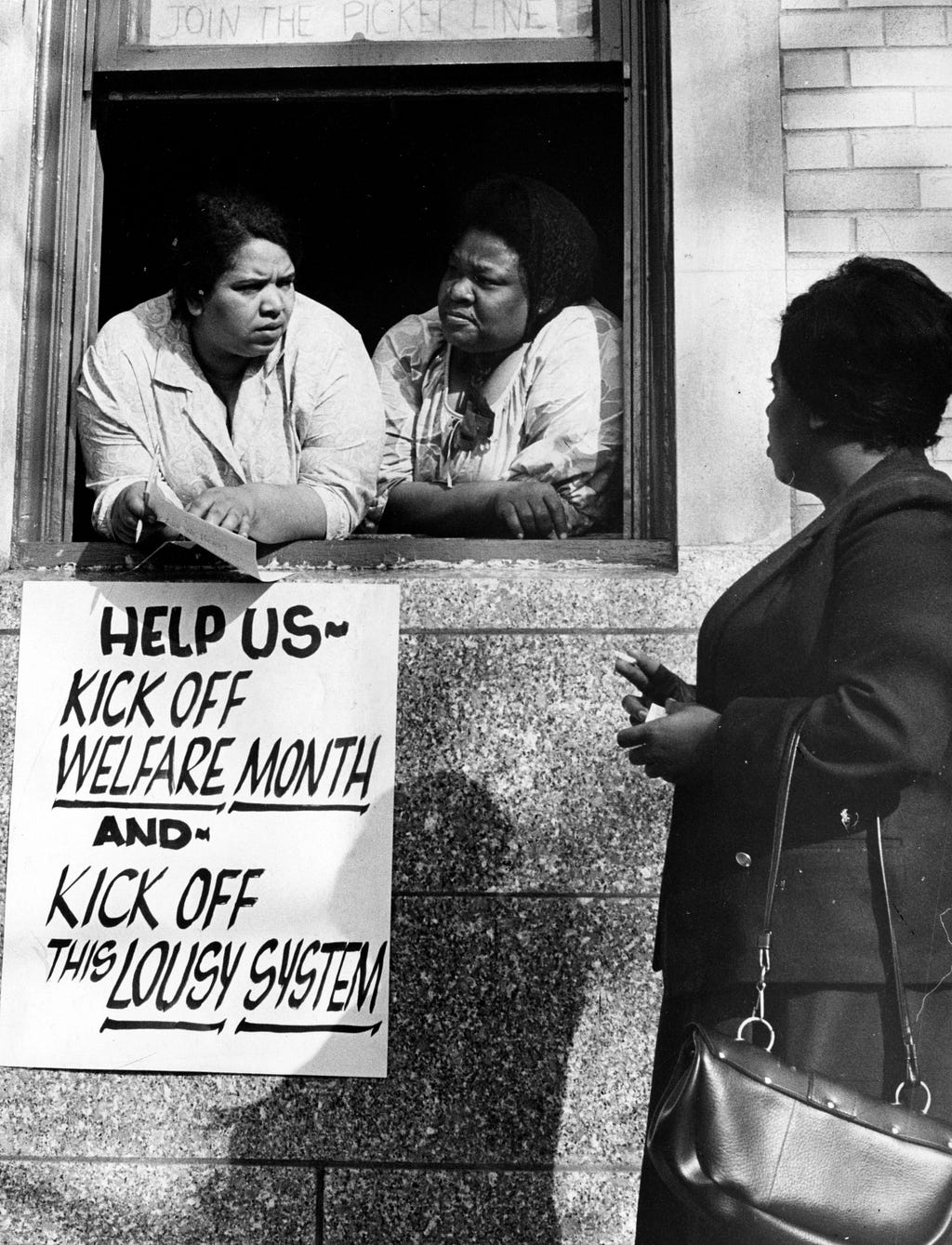

On Friday, June 2, 1967, in the majority black Boston neighborhood, Mothers for Adequate Welfare, a small but formidable citizens group gathered inside of their local social services office — which had “Overseers of the Public Welfare” engraved above its door. They had a list of direct but sensible demands. The action was one of 250 coordinated welfare protests nationwide. In an office where mothers were often mistreated, the women’s demands fell on hostile ears.

Welfare offices had a reputation for showing black residents the worst of what Boston had to offer. Residents felt that caseworkers doled out benefits capriciously, and unfounded, malicious gossip could lead to the termination of benefits. Families felt uneasy in welfare offices, where police stood watch, often armed, and residents had access to staff only one day a week. A growing group of neighborhood mothers was incensed. They staged sit-ins and marches on both local offices and the state house. Though the relative harmony had given way to some promises from the city, these mothers felt progress had not come fast enough.

JJessie Herr, a caseworker at the Blue Hill Avenue office would later tell The Boston Globe that everyone had it rough in the welfare office. Conditions were “terrible,” and they were even worse for families. Crowding was rampant, caseloads were untenable, and budgets were paper-thin. Sumner McClain, a caseworker who had quit his job a year earlier, said he had left 90 cases on his desk on his last day, and told the same reporter that “welfare checks were occasionally being cut without notice because of a shortage of clerks.”

Compared to other major cities, where tensions between black and white citizens had been simmering and boiling over for the nation to see for years, Boston had appeared to weather the storm. Even in the summer of 1966, when a few violent incidents stoked talks of a riot, local authorities collaborated with local organizations and leaders to allow cooler heads to prevail.

On June 2, 1967, cooler heads lost.

The mothers came demanding the removal of officers from the welfare building, increased availability of staff, and increased respect from welfare office staff, among other requests. When they were told the office was set to close up for the weekend, they were having none of it. They wrapped the exits with bicycle chains to keep employees inside while a few mothers made their way to a first-floor window and hung out a sign. When employees called police to report an older worker’s apparent heart attack, police and emergency workers arrived on the scene, as did the office’s director, Daniel J. Cronin. The police couldn’t break the chains from the outside.

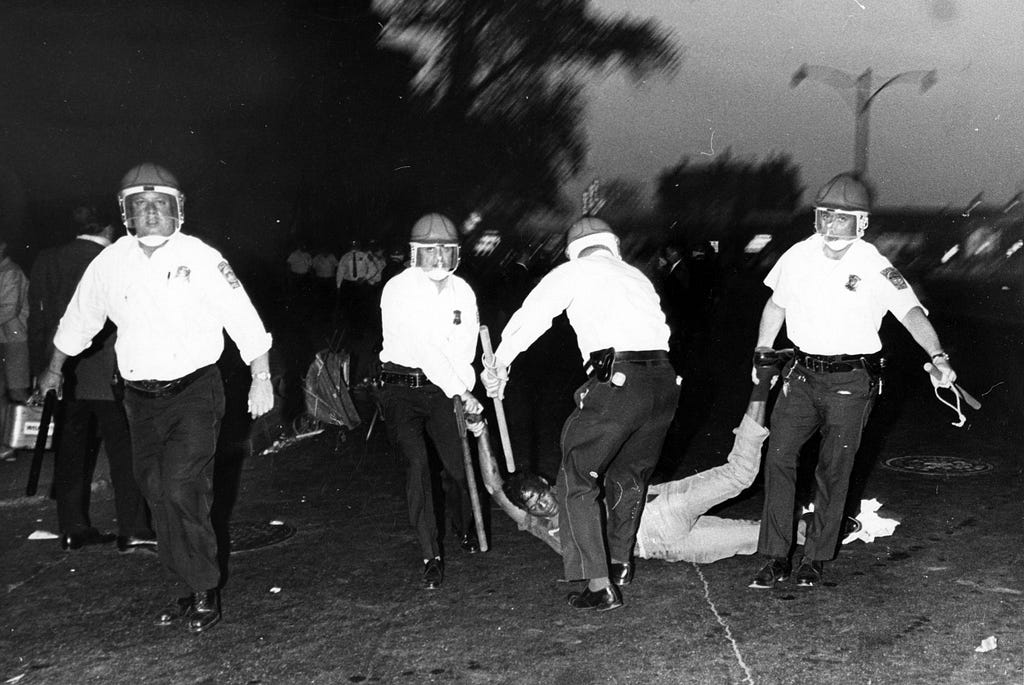

Shortly after his arrival, Cronin refused to meet or speak with the mothers in view of the crowd, despite this being their third protest in eight days. While he held forth, 30 police officers entered the building through a broken window while firemen removed employees. When Cronin made it clear the mothers wouldn’t get their meeting with locked doors, police then rushed the exit from the inside, breaking the chains and clashing with the concerned residents who had gathered our front.

By this time, the crowd had grown well into the hundreds, brought to the scene by the sights and sounds of the approaching paddy wagons and cruisers.

Police wielding billy clubs and riot gear rushed residents in an effort to disperse the crowd. A Harvard student at the scene told his school’s newspaper that officers were shouting “kill ‘em” as they beat residents back.

The night had only begun. In the hours that followed, the neighborhood would show its frustration to anyone watching — including authorities and media — and the city would meet that anger with swift force. Groups large and small pressed the hive of Boston’s Finest from disparate points. Twenty at a time, then 80 when the 20 were done, then more, and more to follow. What these fathers, sons, mothers, and daughters lacked in coordination and equipment, they compensated for with sheer will.

Soon enough, rioters branched off from the direct clash with Boston Police. A popular furniture store was set on fire, nearly three dozen other businesses were looted. Police would end up firing almost 100 rounds at 200 protesters.

The morning light would give full view to the weed of unrest that had grown from the seed sown by a small group of mothers. By then, 1000 officers had arrived, with clubs and guns. They faced an opposing crowd that nearly matched them, body for body. The damage done to the busy Boston street totaled more than $3.7 million in modern dollars. The damage — for which residents blamed police — was visible beyond raw numbers: A Globe reporter recalled blood running down the face of a small boy cut by broken glass as “weeping women, unmindful of their own safety, search the milling crowd for lost children.”

Behind the scenes, Kenneth Guscott, president of the Boston branch of the NAACP, got a meeting with the mayor. In it, he’d pressed the city to agree to the most urgent police-relations issues, including restrictions on gun usage and name-calling by on-duty officers. The mayor agreed.

Even so, groups of angry local youths were taking to the streets in even larger numbers than the night before. Cars were flipped, windows were broken, and police and firefighters were called again.

Lt. Joseph Donovan was part of a group of firemen that responded to a call in the Grove Hall section of town, which linked the black neighborhood of Roxbury to the adjacent white neighborhood of Dorchester. The unrest had become so dangerous that armed officers were assigned to ride on every truck. Shortly after Donovan’s truck arrived, police said it was pinned down by sniper fire, and Donovan was shot in the hand.

By nightfall on the second day, police numbers had swelled to 1900, bolstered by the commissioner’s cancellation of time off. Local leaders and city brass butted heads over how to quell the rage of the rioters. Reverend Virgil Wood told newspapers that “war was declared on the black people by the police force.” Despite the tacit acceptance of the rioters’ point of view, local clergy still collaborated to stage peace vigils, to make their neighborhoods “a safe haven of healthy citizenship.”

The second night would see police bring bayonets and machine guns to face the barrage of bottles, rocks, and trash.

On that second and final night, 20 were injured, among them Arthur Clements, who was taken to a hospital with a knife wound to the chest, as was 16-year-old Scottie Roystone, who had his skull fractured by a gang. All told, more than 65 injuries were reported, along with more than 50 arrests.

A day after the riots, 125,000 Bostonians lined the streets in nearby Dorchester for an annual parade to greet the Marine Corps marching band.

Today, the area around Blue Hill Avenue is one of Boston’s roughest, with high crime rates, a median income of $34,000 a year, and an unemployment rate double the national average.

Half a century has passed, but many of the same issues that brought angry crowds to Roxbury’s streets in 1967 remain. And what began in a welfare office that warm June day would tear through cities across America, galvanizing a season of resistance, and ushering in what would later be known as the Long Hot Summer.

When this group of black mothers locked themselves in a government office, Boston erupted in riots was originally published in Timeline on Medium, where people are continuing the conversation by highlighting and responding to this story.

Powered by WPeMatico