Why Amazon Bought Whole Foods by @AmericanJebus

It’s about the future of commerce.

Liberal Christmas has arrived. Now you can pay $113231581797321057 to have an Amazon drone deliver farm-to-table, organic avocados to your doorstep! Edible gentrification has never been more convenient.

For the past decade, Amazon has been steadily feasting on the digital world. On Friday, it took a critical step in subsuming the physical world by launching a bid to acquire upscale grocer Whole Foods for $13.7 billion.

It’s a lump sum of money that could’ve ended world hunger, but don’t act like you haven’t already spent $13.7 billion on asparagus water or quinoa or kale or inmate-made goat cheese (isn’t it supposed to be cage free?) at Whole Foods.

As hyperbolic as this sounds, this has implications for the future of groceries, the entire food industry, and the future of shopping for just about everything.

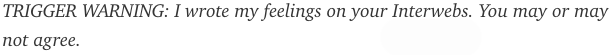

A straightforward analysis suggests this deal represents a simple confluence of interests. Amazon needs food and urban real estate, and Whole Foods needs help with its recently floundering share prices.

Amazon acquires 456 stores nationwide and a slice of the $750 billion grocery market. Whole Foods stores tend to be seated in prime real-estate locations targeting a higher-end demographic. It could become a significant branding boost for Amazon and a way to increase its physical presence.

In the “brick and click” competition, Walmart is trying to bolster its online influence, while the e-commerce giant is approaching it from the opposite end — expanding into groceries and physical locations, including bookstores, ironically working itself back into the brick-and-mortar business that it’s also disrupting.

Since Amazon was a diminutive startup selling paperback books, CEO Jeff Bezos has kept his sights targeted on the long game. In his first letter to shareholders in 1997, he advised investors to strap in for a bumpy financial ride that could include short-term quarterly losses and risky acquisitions to pan out.

He wrote:

“We will make bold rather than timid investment decisions when we see a sufficient probability of gaining market leadership advantages. Some of these investments will pay off, others will not, and we will have learned another valuable lesson in either case.”

In a more long-term and hypothetical analysis of this deal, the first implication is transforming food into a delivery service. E-commerce is soaring and food-delivery businesses are taking off — fewer shoppers and diners are passing through grocery stores and restaurants, as Americans are ordering more of their produce and meals online. There’s also the “grocerant” trend — a blending of grocery stores and restaurants.

Traffic is flat in the restaurant sector, and digital orders are up 45 percent over the last two years. The online market is projected to grow 15 times faster than the rest of the restaurant business through the end of the decade. “Prepared, ready-to-eat” items purchased outside the home are now 1-in-10 entrees served in American households.

Giving flexibility and power to the consumer, enabling them to procure the goods they want, and having them delivered to their front door sounds like a winning business model.

Fresh foods are the final frontier for Amazon, and have proven a tricky challenge for e-commerce giants. If Amazon is to finally fulfill their existential journey of reaching high-volume growth, getting fresh food to front doors is an essential part of the equation.

The deal gives Amazon a major foothold in that space. Whole Foods gives Amazon a tremendous amount of credibility around the quality of the food and the reputation they have with their customer base.

AmazonFresh is Amazon’s foray into the online grocery business during the last few years, but it hasn’t quite mastered it in the same way it’s mastered books and media.

With Whole Foods, which will continue to operate under its own brand name, an Amazon Prime member subscription may operate like a Costco membership. Perhaps Prime members would get deals on Whole Foods produce, and they could elect to have the fresh vegetables and organic dips delivered to their homes and apartments.

This acquisition is a near $14 billion bet on the future of food coming gift-wrapped and delivered in boxes.

This deal is terrifying for its competitors in part because Amazon’s low-margin business pulls each industry it dominates into a kind of deflationary whirlpool. If Whole Foods follows the Bezos playbook, shoppers can expect prices to fall, and investors will expect sales and revenue to rise. Maybe it can finally shed its long-standing derisive nickname, “Whole Paycheck.”

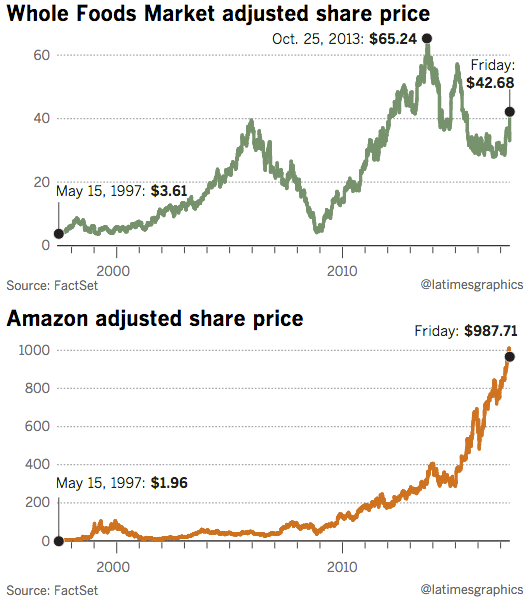

When news broke, Wall Street reacted with grocery chain carnage, as stocks for Kroger, Costco and Dollar General plummeted — all falling more than six percent within the hour. The merger may even prove more gloomy for Instacart, the grocery-delivery service that’s mired in year two of a five-year contract with Whole Foods.

The second implication is Whole Foods functioning as a distribution hub — and Amazon as a physical retail presence. The real estate value of Whole Foods’ urban and suburban locations are worth so much, and are so strategically integral for Amazon’s delivery business, that even if the grocer stopped selling food altogether, several analysts have said the deal would still prove successful. As Dennis Berman, Wall Street Journal’s financial editor, Tweets:

Amazon did not just buy Whole Foods grocery stores. It bought 431 upper-income, prime-location distribution nodes for everything it does.

Amazon is trying to become Walmart faster than Walmart can become Amazon. Soon enough, it won’t be merely an online megalith, but also a physical retail powerhouse with dynamic pricing and stocking strategies.

This deal has the makings of wide-scale, far-reaching ramifications to many industries — restaurants, pharmacies and drug stores, maybe even ride-sharing companies. Amazon is taking on a behemoth of a logistics challenge.

In December, Amazon debuted its flagship grocery store in Seattle with with no checkout line. Customers check in at the store’s entrance with an app called Amazon Go, collect their groceries and walk out, all without having to interact with another person. This model has the potential to expand. The deal also places pressure on Amazon to keep developing a smart shopping cart that can charge customers automatically whenever they drop in.

With more of our shopping visits digitally enabled, this will only continue to grow. Increasingly, we’ll be doing everything from home, meaning delivery and pickup systems are ripe for disruption.

AmazonFresh is already experimenting with a “click and collect” system; shoppers buy groceries online, then pick them up in person.

With something like dugs, Amazon, whether intentional or inadvertently, is building the foundation of the logistical infrastructure for an industry that requires specialty pharmacies and a very specialized distribution of medications.

With more brick-and-mortar hubs, they can take on more complex logistical challenges digitally.

This can also change the nature of a retail job. Now, a retail worker will have to be someone who can figure out how to manage these complex systems, not someone who will be checking customers out. The one-dimensional jobs of cashiers, stockers, greeters, and others will soon be relics of a department store’s past.

However, supermarket chains aren’t an easy business — it’s currently being disrupted by meal-kit delivery services — and the concept of a grocery store could be completely reimagined a decade down the road. These stores could evolve and experiment — maybe teaching cooking skills, hold classes, and educate about dieting and nutrition — a whole repurposing of the brick-and-mortar concept.

The third implication is Amazon is becoming a “life bundle,” particularly for affluent Americans. Much like a cable bundle, Amazon could become an annual subscription to a fleet of an array of services that’s fundamentally about the merchandizing of convenience.

Driving to the movies and parking is a pain. Driving to the grocery store, finding parking, seeking out the produce section, waiting in the deli line just after the dimwit who takes an eternity to choose whether they want honey glazed ham or buffalo chicken, and waiting several minutes in line behind register 4 is an annoying inconvenience.

Americans these days are harried, increasingly lacking time to shop, cook, or dine out. An average Friday night could be spent lying on your couch, watching 10 Cloverfield Lane on Prime Video, and hollering to your Amazon daemon, “ALEXA! I need six heirloom tomatoes, extra-virgin olive oil, and a bottle of wine for tonight’s delivery.”

Between Prime and Whole Foods, Amazon may now account for a majority of some urban Millennials’ discretionary spending — a growing, devoted customer base of affluent yuppie Americans. More than half of American households with income over $100,000 are already Prime subscribers, spending over $1,000 a year as wealthy families regularly spend $500 a month on Whole Foods.

Amazon could feasibly expect its richest customers to spend thousands of dollars a year through Amazon. Even as it offers discounts to lower-income Americans, Amazon will continue its full scale assault to penetrate the affluent yuppie market. Whole Foods customers will be urged to sign up for Prime and Prime customers will get enticing deals at Whole Foods.

Amazon is already an Internet goliath, whose products affect nearly every online user.

If you’ve ever received an Amazon package, watched a livestream on Twitch, or checked an actor’s filmography on IMDb, you’ve dealt with the retail giant’s properties directly. If you’ve streamed a movie on Netflix, booked a flight on Expedia, or sent a selfie on Snapchat, you’ve also felt Amazon’s reach via its cloud computing services, now in use by more than 1 million online businesses.

Now that Amazon is taking its first steps offline and into the physical world, at what point do we start talking about anti-trust? Or is this just a platform change?

Amazon and Whole Foods are complimentary businesseses, and this acquisition could be the harbinger into Amazon’s evolution into an infrastructure and logistics company.

Sears rose to prominence as a retail titan last century with its 500-page “Consumer’s Bible,” which popularized the mail-order business. But in the early 1900s, as families moved to the cities, Sears followed, building more than 300 stores between 1925 and 1929 that specialized in the hardware needs of the growing middle class.

Amazon’s strategy continues this pattern, ascending to retail stardom with as a browsable couch product — its website and delivery service during a rapidly digitizing and interconnected world that makes the antics of grocery shopping a fading pastime.

But the future of its business may include more urban and suburban stores that both hold merchandise for delivery and permit consumers to shop.

It’s funny how the future can look like a familiar reconstruction of the past.

Powered by WPeMatico