Why I can’t put down The Binding of Isaac

Have you ever tried to shovel snow that’s already piled up to your shoulders? I have. It’s something that everyone in New England has to get through once or twice in their life. It’s a frustrating experience, because you’re so deep into your situation already that the actual physical process of scooping the snow up becomes very hard to manage. The toughest part is actually getting the first scoop of snow onto the shovel, because there’s already so much snow in the way.

That, in a way, is how I feel when trying to talk about The Binding of Isaac, a game that has entertained me for so long that it almost feels like a natural part of my life. There’s so much to dive into, so much to talk about, that I’ve been putting off writing about it for a very long time simply because I don’t know where to start. I suppose, though, it’d be best to start at the beginning which is, as the old song goes, a very good place to start.

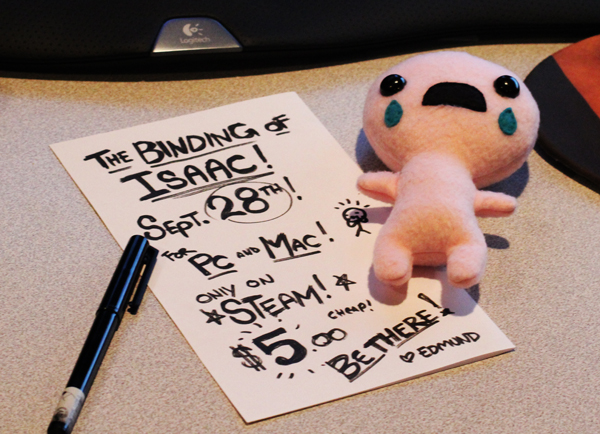

The Binding of Isaac was released in September, 2011. It’s a top-down roguelike where the player controls the eponymous Isaac in his endeavor to escape his homicidal mother by delving further and further into his basement. Initially, Isaac is only protected by his tears, which he fires at enemies as projectiles. Randomly chosen items that the player finds along their way will upgrade and improve Isaac’s chances at success, sometimes even drastically altering the way that the game is played. Of course, each run’s items are randomized, and with so many items in the game, it’s incredibly unlikely you’d ever get the same set of upgrades twice.

I purchased the game as a college sophomore, shortly after it released. It was the first roguelike I had ever played, and the idea of tackling the same floors of a dungeon over and over again was an idea that, at first, didn’t appeal to me. In fact, I distinctly remember being disappointed that I had to do it all over again after my first death, and nearly closed the game.

But I didn’t.

The gameplay look of exploring, shooting, and upgrading had hooked me, hard. The subtle nuances of curving your shots by lateral movement already had me eager to master the basics and, though I never actually got out of the first floor on that run, I did manage to find an item room and upgrade Isaac’s fire rate; I was eager to see what other items awaited me in the game. In short, I was instantly addicted.

I would go on to play other roguelikes. Lots of roguelikes, in fact. Nethack, Dungeons of Dredmor, Risk of Rain, Rogue Legacy, FTL, and even the original Rogue, but the one I kept coming back to was Isaac. It certainly didn’t help that most of my college friends played the game, or that we would consistently meet up after classes to hang out and play the game together. Not co-op, mind you, just four nerds sitting around a lounge with laptops in hand, all playing and sharing tips. We did this for years, and it never once got stale.

Of course, a huge part of that was Ed McMillen’s massive update to the game, Wrath of the Lamb. It changed the way that we played the game, from the bottom up. New items, new abilities, new bosses, new enemies… It was nearly a total do-over, and it was excellent. Unfortunately, the cracks in the foundation were beginning to show.

Isaac was coded in Flash which is, to be frank, a wonderful program that was simply not meant to handle a game on the scale of Isaac. Regardless of how beefy your gaming rig was, the framework of Flash caused slowdowns and problems for everyone playing. It didn’t happen often, but after a while I just accepted occasional slowdowns and lag as part of the game. I figured it was just the way things were, and that was that.

When The Binding of Isaac: Rebirth was announced, my friends and I lost our collective minds. More items! More enemies! More floors to explore! And best of all, a rebuilding from the bottom up in a game engine that didn’t use Flash! Oh, it was more than my feeble heart could take. I eagerly devoured the game, and played it nonstop for a few weeks. It was everything that I had hoped for, and more.

Unfortunately, Real Life™ got in the way and I ended up putting the game down for several years. I only recently picked it back up when I purchased my Nintendo Switch back in March, and I’m damn glad I did. The game feels more precise on a controller than it ever did using a keyboard, and the Switch’s portability and ease of use vastly improved my overall gameplay experience.

So, what makes the game so damn fun? I wish there was an easy answer, but even after 200+ hours of gameplay across all the versions of the game and the various systems I own it on, it’s hard to pin down any one definitive answer. It would be simple to just say “replayability” but the real answer is much more complex. The game’s enjoyability, for me, comes down to several factors that affect every level of gameplay.

. . .

The first, and most obvious on a surface level, is the vast and overwhelming library of items and powerups that Isaac can find in-game. The Steam page for rebirth proudly boasts over 450 items though, in any given run, the player is likely to only find about 15 to 20 of these. Each of these items allows to the player to make an adjustment to the way they play the game. A few examples with demonstrate this rather easily.

Cupid’s arrow allows Isaac to fire shots that pierce enemies. Even though your damage output is unaffected at its base level, a room full of enemies instantly becomes easier to parse and work through than it did before. Flies, which are individually pretty harmless, can become a major nuisance in large groups, and an item that damages multiple enemies at once, like Cupid’s arrow, can do a lot to keep the player safe in such circumstances. Other enemies, like the Knight, can only be damaged from behind. Again, though Cupid’s arrow does not actually increase your damage output in any way, these dangerous enemies become a minor inconvenience.

Other items have effects that are purely utilitarian and have no connection with combat. There are several items which grant Isaac the power to fly over obstacles in a room, a power which has little combat use outside of dodging enemy attacks but can drastically improve the player’s overall chances at winning a run by allowing him to collect items which would ordinarily be out of his reach.

The Gnawed Leaf, another utilitarian non-combat item, turns Isaac into a statue that cannot be damaged if he stands still for two seconds. Though not too useful in Mario 3, this tanooki-suit parody is so strong in The Binding of Isaac that I personally take it as an assurance that I will win a run. So long as I have an item that damages enemies without me needing to move, like the Pretty Fly or Mom’s Knife, I’m almost certain to beat any boss in the game simply because I can hurt them, and they can’t hurt me. There are exceptions, of course, but if victory was guaranteed, where would the fun be in that?

Of course, there are items that purely increase the damage that Isaac puts out, and they are always welcome. Items that make Isaac’s tears explode, or fire lasers, or simply make bombs more effective. According to Ed McMillen, there are over 4 billion distinct seeds for the game – that means 4 billion different combinations of items and 4 billion ways to adjust your strategy. That’s a lot. More than anyone could experience in a lifetime. That’s certainly one definition of “replayability”.

. . .

The second factor that I would attribute the game’s enjoyability to would be consistency. Yes, despite the 4 billion different basement layouts and item combinations, the game would be almost too difficult to play if there was no consistency between runs.

Enemies, for example, have set routines. Individually, enemies are very simple. Most have an extremely limited set of verbs they can act upon. Attack flies, for instance, wander towards the player. That’s all they do, ever, so if you see a room full of attack flies you can easily manipulate their movement with a little practice in order to make them a more manageable foe. The danger these enemies pose to a more experienced player is very low, but a swarm of these flies can force the player into a compromising position within the room if he lets them get out of hand.

Knights are a bit more complicated, and are a staple of later floors. They bumble around aimlessly until the player falls into their line of sight, at which point they speed up slightly and make a charge straight towards Isaac until they hit a rock or a wall. Because they follow this behavior pattern consistently, the player is able to get behind them and hit them from behind on their weak spot.

Now, facing a single knight or attack fly poses almost no challenge for any player that understands their patterns. Combinations of enemies, however, is where things get interesting.

If the player were to encounter a group of knights in a room stuffed with fly-spawning hives, difficulty would skyrocket. This is not because the enemies act in unpredictable ways, but because the player now has to juggle two enemy patterns in their head at once. The knights move in straight lines, and require the player to trick them into charging in order to damage them consistently, while flies just set course straight for the player. That means that the player doesn’t have the optimal approach for getting rid of the knights because Isaac needs to be moving almost non-stop in order to avoid damage.

Enemy combinations like these are the bread and butter of the Isaac experience, and can create a great deal of tension and danger for the player. The game isn’t difficult because enemies do a lot of damage; the game is difficult because it forces the player to stay on their toes while understanding complex and shifting patterns of movement and attack. There are so many combinations of enemies and attack patterns that can be thrown at the player that the game never seems stale. Even with over 200 hours under my belt, I still manage to find new encounters from time to time. For more information on how consistent AI impacts player experience, I would recommend this video by Marc Brown over at Game Maker’s Toolkit, an excellent series that explores all the behind-the-scenes stuff that makes games so darn fun even if the player never outright notices it.

. . .

My final and definitely my most subjective factor that makes The Binding of Isaac such an enjoyable experience is also perhaps the most important: the simple sense of satisfaction the game is able to give.

No matter which character you decide to start a run as, it is a given that you are underpowered. With exception to Azrael, the only character that starts with, in my opinion, an incredibly overpowered basic attack, all characters in Isaac start with low damage output and very few, if any, special skills. This only serves to compliment those runs where everything seems to be going right, and you’re just destroying every enemy in your path. As Disney’s Hercules once said, it’s all about going from zero to hero.

The game allows you to have an unreal amount of fun just by giving you so many options and, sometimes, making you so overpowered that nothing can stand in your way. Seeing those giant full-damage tears smash into enemies and pop them instantly is satisfying. The sound effects and visual feedback feel good.

See, like I said – this one’s subjective.

It’s difficult to put game-feel into words, but I’ll try my best: Controls are tight and responsive, despite frequent changes to your move and shot speed. Firing tears is, on paper, as simple as pressing the direction that you want to shoot, but in practice requires timing, mastery of movement controls, and sometimes, when powerups are involved, a bit of luck. It looks like Ikari Warriors but feels like Doom’s plasma gun.

One thing that Edmund McMillen seems to excel at in all of his games is making player death feel fair, but not making a big deal out of it. In his breakout hit Super Meat Boy, after a death the player is instantly respawned at the beginning of the level so fast that you forget you even died. Isaac works similarly, allowing you to start over almost as soon as you die. There’s no slow “GAME OVER” text that fades in to rub salt in the wound, or some long cutscene that shows Isaac’s slow and painful death. No, there’s just a half second of Isaac going “Aah!” and then you’re back in the game.

. . .

What I’m trying to say with all this is that The Binding Of Isaac feels good because every single system in the game rewards the player for playing well and understanding the game. The strategies and run variations are functionally infinite, and while the actual act of squashing enemies and fighting bosses is fun in and of itself thanks to a tight control scheme and good visuals, the real joy comes from leveraging your assorted powers to their best advantage and figuring out how to turn a bad run into a good one.

Ed McMillen knows how to make games. He knows what’s fun, and he cuts out what’s not. The Binding of Isaac is a fantastic example of that particular ideology, and with McMillen’s new game The End Is Nigh fast approaching on the horizon, I can’t help be be hyped for what’s he’s got for us next.

Stay safe out there, dear reader, and don’t wander into any trapdoors.

Powered by WPeMatico